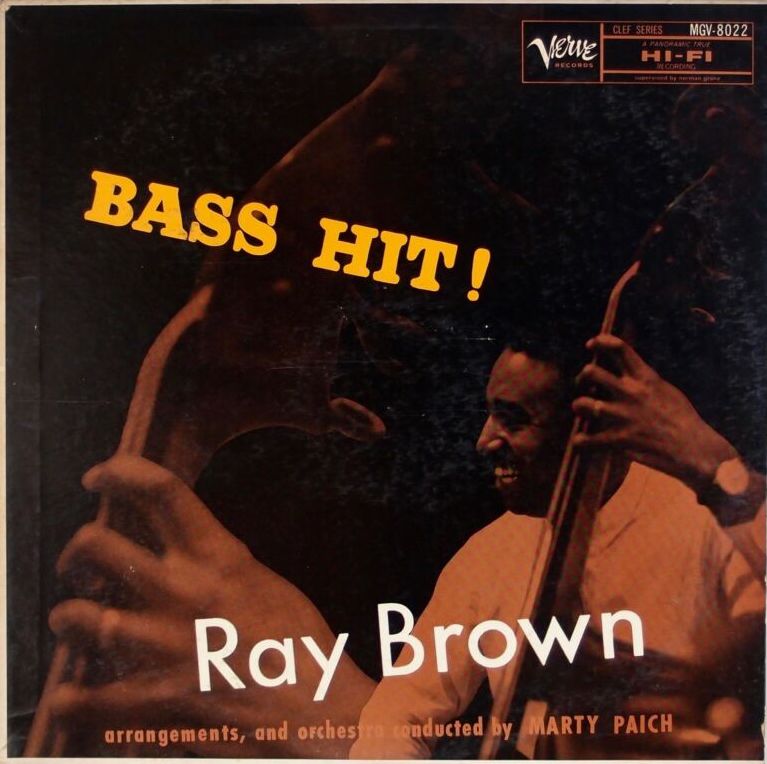

Ray Brown fronting an all-white band in 1956 was a major musical-social event. Bass Hit also happened to be a beautifully conceived hot date.

Personnel

Ray Brown (bass), Pete Candoli, Conrad Gozzo, Ray Linn & Harry “Sweets” Edison (trumpet), Herbie Harper (trombone), Jack DuLong & Herb Geller (alto saxophone), Jimmy Giuffre (clarinet, tenor saxophone), Bill Holman (tenor saxophone), Jimmy Rowles (piano), Herb Ellis (guitar), Mel Lewis & Alvin Stoller (drums), Marty Paich (arranger)

Recorded

on November 21 & 23, 1956 in Los Angeles

Released

MG V-8022 in 1956

Track listing

Side A:

Bass Introduction/Blues For Sylvia

All Of You

Everything I Have Is Yours

Will You Still Be Mine

Side B:

Little Toe

Alone Together

Solo For Unaccompanied Bass

My Foolish Heart

Blues For Lorraine/Bass Conclusion

Ray Brown’s flawless technique, abundant swing and elegant interplay got him at the top of the heap, playing with Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Count Basie, Benny Carter, Illinois Jacquet, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Milt Jackson, Oscar Peterson, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Frank Sinatra. The list is endless. His work with the Ray Brown Trio in the 80s and 90s – Brown intermittently worked in the Hollywood studios – is peerless and his influence on subsequent generations is everlasting. Most of all, Brown, himself influenced by the legendary Jimmy Blanton, had a great, buttery tone and a unique gift for finding the right note at the right time. Ooh wee. How many times have I listened to an Oscar Peterson record and, for all Peterson’s commanding virtuosity and swing, have felt myself being inevitably drawn to Ray Brown, like a kid to the candy store? His enormous energy was overwhelming. I saw him perform just this once in my hometown’s legendary jazz club, Porgy & Bess. Brown’s giant groove, underscored by the radiant grin on his face, drove the band through the roof.

Brown, Pittsburgh-born, came on the scene in New York in 1946 and established himself from the word go. His alliance with Oscar Peterson in 1951 led to worldwide recognition and, by his own account, made him a considerably better player. By 1956, Brown had contributed his outstanding skills and groove to, among others, Johnny Hodges’ The Blues, Count Basie’s Basie Jazz, Roy Eldridge’s Rockin’ Chair, Benny Carter’s, Alone Together, Billie Holiday’s Lady Day, Lester Young’s Prez & Sweets, Charlie Parker’s Big Band, Illinois Jacquet’s Swing’s The Thing, Dizzy Gillespie’s Diz And Getz and Roy And Diz, Hank Jones’ Urbanity, Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong’s Ella & Louis and an ever-growing slew of Oscar Peterson records. Almost all of them were on the Clef and Verve labels of Norman Granz, for whom the dependable and brilliant Ray Brown was a godsend.

Come 1956. Times were rough. The Supreme Court decision of Brown vs Board Of Education was a landmark event in 1954. It established the unconstitutionality of segregation in public schools. However, the ruling, further recorded in BBE part 2, proved something of a Pyrrhus victory, as states could choose to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” Then there was Rosa Parks, who courageously refused to give up her seat in the segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955. Some brave women, lest we forget – like Claudette Colvin – preceded the Montgomery Bus Boycott but it was Parks that turned into a symbol of rebellion and civil rights. Finally, the state court repealed bus segregation on November 16 – a week before the Ray Brown session. The protests nonetheless backfired considerably. Jim Crow wasn’t about to give in that easily.

The mid-50s was an era in which many black musicians still hesitated when the opportunity of touring the South arose. If they did travel south, they were not allowed in white-owned hotels and bunked at private places. Against this background, a jazz outing like Bass Hit – a black man leading a white orchestra – is significant. Jazz, like any great art form, may have been the battleground of plenty of cultural warfare but it never failed to contribute to progress and the growth of understanding, much in a fashion that Martin Luther King would have appreciated. Benny Goodman hired Teddy Wilson and Charlie Christian. Pearl Bailey was married to Louie Bellson. Miles Davis was, with sound reason, a motherfucker with an attitude, but Bill and Gil Evans were, for an eponymous time, his main men. The list of groundbreaking interracial mingling is impressive. Jazz, at its best, has no borders of any kind, is a game changer equal or arguably superior to the political process.

Bass Hit was recorded on November 21 and 23, 1956 in Los Angeles. It featured Pete Candoli on trumpet, Herbie Harper on trombone, Jack DuLong on alto saxophone, Jimmy Giuffre on clarinet and tenor saxophone, Bill Holman on tenor saxophone, Jimmy Rowles on piano, Herb Ellis on guitar and Mel Lewis on drums. Altoist Herb Geller and trumpeters Ray Gill, Conrad Gozzo and Harry “Sweets” Edison (black but a minor role) strengthen the reeds and brass. Drummer Alvin Stoller subbed for Mel Lewis on a few cuts. Marty Paich was the arranger.

I’ve always wondered how it came about that Brown fronted an all-white band, yet there’s not much in the way of recorded evidence or info. Therefore, I reached out to Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven from Lausanne, Switzerland, whom I came to know through the jazz forum Jazz Vinyl Lovers on Facebook. 56-year old Jean-Michel grew up with parents who were passionate lovers of jazz and befriended many visiting jazz legends. At age 3, Jean-Michel sat on the lap of Count Basie. When Jean-Michel was a young man, Ray Brown, having grown tired of managing himself, asked the young jazz buff to do his management. Jean-Michel managed Ray Brown for many years and, in the process, also worked for Harry “Sweets” Edison, J.J. Johnson, Joe Pass, Monty Alexander and many more.

Coincidentally, when we talked on the phone, it turned out that decades ago Jean-Michel had been visiting jazz club Porgy & Bess in Terneuzen regularly in his managerial role, at which time I, unbeknownst of his existence, was also present during performances of some of the jazz legends. A clear case of amazing serendipity, which warms my heart.

At any rate, here’s what Jean-Michel found out about Bass Hit through his conversations with Ray Brown and, to a lesser extent, Jimmy Rowles, Mel Lewis and Pete Candoli:

“It was Ray’s idea to do a big band album with him as a feature. Of course, a decade earlier Ray was featured on One Bass Hit and Two Bass Hit, which he wrote for Dizzy Gillespie. Ray told me that he had had in mind the idea of making a record with the bass as lead feature for many years. But his idea was too advanced for that time and in the late 40s you could hardly hear the bass. He always talked about it with Norman Granz, who approved of the concept. But the years went by, till Ray finally said it was the time to do it.

“Why did he record in Los Angeles? Well, in those days, the Oscar Peterson Trio did about 299 concerts in 300 days, it was crazy! The only way to do it was Los Angeles, because contrary to New York, they had long engagements on the West Coast, like two or three weeks at Zardy’s. So recording in Los Angeles was most convenient.

“Ray called his friends. Marty Paich. He loved the arrangements of Paich. Jimmy Rowles, Herb Ellis, Mel Lewis. Everybody was delighted to cooperate with Brown on such a special session. Ray wasn’t conscious of the fact that he was to lead an all-white band. He just called the friends that he wanted for the job. There weren’t many black people in the movie studios. Only a few, like Benny Carter. Now this record had a lot of impact. But Ray did not plan this in advance. He said: ‘Suddenly the producers and writers thought, man this guy leads, reads charts, does amazing solo’s, everything! It opened doors for black guys, they can do the job. A few months after the release, I got many offers, I couldn’t believe it! But I refused. I played jazz and wanted to travel.’ Of course, in 1966 Brown did eventually move to Los Angeles to play in the Hollywood studio bands. By then, he had cleared the path for Quincy Jones, J.J. Johnson, Benny Golson, who all made a career in the movie business.

“Oscar Pettiford had done bass-driven records but those were not arranged and organized as immaculately and not all-white. Bass Hit is the first record that showcases such an impressive lead role of the bass. At the same time, it works sublimely as accompanying force. Most of all, it is not just important on a musical level. It broke down social barriers. Jazz, like any great art form, is a force of change. Its great ambassadors definitely surpass the flawed ambitions of politicians.”

Bass Hit, the album: Brown firmly and authoritatively leads this band of top-notch contemporary white musicians. There is much to enjoy, not least the spicy muted trumpet of Pete Candoli, Herb Ellis’ earthy guitar, Bill Holman’s supple tenor saxophone and Jimmy Giuffre’s clarinet, which adds graceful coolness to Bass Hit’s essentially ‘hot’ program.

Ray Brown is boss, shading melodies, providing succinct interludes and concise melodious and strong solos, while the punchy arrangements cleverly underline Brown’s agile phrasing, as if he’s a singer, as if he’s, in a sense, Sinatra in front of the Count Basie band. Brown and the orchestra blend like strawberry and whipped cream, courtesy of Brown’s immaculate time feel, allowing him to fluently anticipate the brass and reed accents. Bass Hit is commonly called his record debut as a leader, while in fact Brown released New Sounds In Modern Music on Savoy in 1946. Bass Hit’s title alludes to that era, when Brown contributed One Bass Hit and Two Bass Hit to the Dizzy Gillespie orchestra. It presents a set of unabashed big band blues, poised balladry and mid-tempo standards.

You’ll hear a striking descending bass figure, taken from the potent Solo For Unaccompanied Bass, effectively and attractively introduce the record and segue into the opening tune, Blues For Sylvia. More blues, Blues For Lorraine and Brown’s Little Toe, firmly directed by Brown, penultimate blues groove master, ties together the threads that consist of well-known ballads of which Cole Porter’s All Of You is particularly notable. The detailed conversational level of the piece, especially the whispered staccato call and response of Brown and brass/reed, slyly heightens the tension. The booming release hits bull’s eye.

Bull’s eye, as a matter of fact, was second nature to the great Ray Brown.