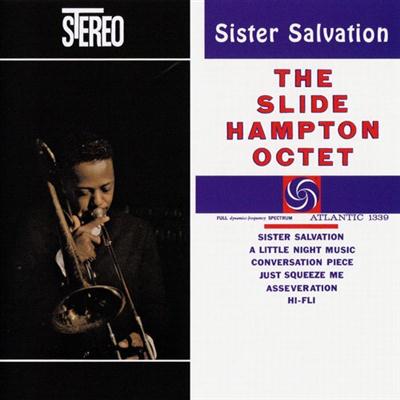

Sister Salvation is trombonist and arranger Slide Hampton’s breakthrough album as a leader. It’s another one of those typically soulful, warm-sounding, big ensemble productions of the Atlantic catalogue of the early sixties – like the albums of Hank Crawford, David Newman and Milt Jackson. Too good to miss.

Personnel

Slide Hampton (trombone, arranger), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Ernie Royal (trumpet A2, B1-3), Richard Williams (trumpet A1, A3), Bob Zottola (trumpet), George Coleman (tenor saxophone, arranger), Jay Cameron (baritone saxophone), Kiane Zawadi (euphonium), Bill Barber (tuba), Nabil Totah (bass), Pete LaRoca (drums), Billy Frazier (arranger)

Recorded

on February 11 & 15, 1960 at Bell Sound Studio, NYC

Released

as Atlantic 1339 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Sister Salvation

Just Squeeze Me

Hi-Fli

Side B:

Asservation

Conversation Piece

A Little Night Music

Nowadays it’s hard to fathom the kind of incredible jazz life Slide Hampton led. Already playing trombone by the age of three, Hampton toured the US with the (XL) family band of his father, providing music at carnivals, circuses and fairs. As a young man, Hampton’s stature grew by playing with Lionel Hampton (no family relation), Dizzy Gillespie and Maynard Ferguson, displaying both his fluent trombone playing and superb arrangements. By 1960, a recording as a leader by the cutting-edge Atlantic label was more than appropriate. (The release of Slide Hampton And His Horn Of Plenty a year earlier on the obscure Strand label had gone relatively unnoticed) In 1960 Hampton also played on Charles Mingus’ Mingus Revisited and Randy Weston’s Uhuru Afrika.

Asservation is a succesful blend of small combo flexibility and big band muscle. One constantly imagines a singing voice prying for attention and I think that kind of vibe is one of the tune’s and album’s greatest qualities. Sister Salvation assuredly has that ‘singing voice’ quality, you’d expect the voice of “Brother” Ray Charles to chime in any minute now. It’s churchy, r&b-type jazz at its best.

A Little Night Music, a more lithe, bouncy tune with a pronounced descending bass line, is contagious as well. Hampton also picked interesting tunes of other composers like Randy Weston’s Hi-Fli and Gigi Gryce’s Conversation Piece, that include concise, top-notch solo’s by Freddie Hubbard and George Coleman. In short, the album is a happy marriage between tunes, arranging and soloing.

The jazz life of Slide Hampton would continue, bringing many more recordings in the sixties, a job as arranger at pop soul-kingdom Motown and fruitful years as a jazz expatriate in Europe in the seventies and beyond. Hampton has been especially prolific as a recording artist in the new millenium. Twin Records released Hampton’s latest album, Inclusion, in 2014.