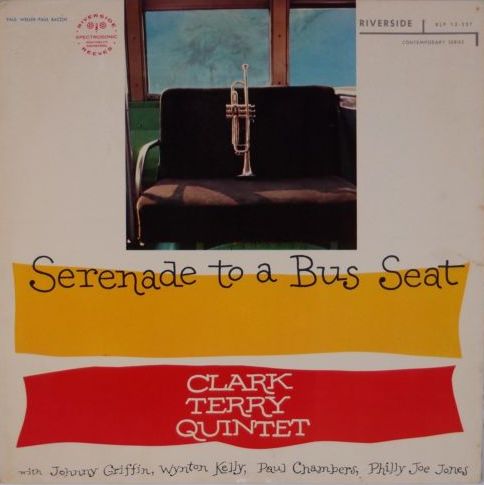

Clark Terry, who passed away in 2015 at the age of 95, was an authority with a discography of epic proportions. In 1957, already a veteran of swing who had mentored rising stars like Miles Davis in the 40s, the trumpeter made a superb hard bop album with Johnny Griffin, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, the Riverside label’s Serenade To A Bus Seat.

Personnel

Clark Terry (trumpet), Johnny Griffin (tenor saxophone), Wynton Kelly (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Recorded

on April 27, 1957 at Reeves Sound Studio, New York

Released

as RLP 12-237 in 1957

Track listing

Side A:

Donna Lee

Boardwalk

Boomerang

Digits

Side B:

Serenade To A Bus Seat

Stardust

Cruising

That Old Black Magic

Before turning into an internationally renowned figure through his seat in the orchestra of NBC’s The Tonight Show in the 60s, his vocal hit Mumbles, lauded appearances around the globe and a distinguished position as youth educator and (co-)founder of Jazz Mobile and the Clark Terry Jazz Festivals for the rest of his life, Terry already had a timelessness about him that is striking. He encompassed the best traits of the past while being in sync with the conception of the modernists, using his technical brilliance and vast knowledge of what one can achieve with the trumpet to the telling of meaningful stories. Not a term usually associated with the abundant Terry, he actually set a limit to himself in this regard, displaying effects and humor when it was called for by Duke Ellington for a certain compositional story to tell, or when he expressed his feelings as a sideman (Oscar Peterson Trio + One is an outrageous ball, but a structured and hi-level festivity) and leading artist, mostly feelings of distinct joy.

His long stint in the Duke Ellington Orchestra in the 50s was preceded by years with Count Basie in the 40s, and Terry was a featured, singular soloist in both classic bands. Nice resume. In fact, in 1957 Terry had just left Ellington, with a number of classic recordings in his hip pocket, notably Ellington Uptown, Such Sweet Thunder and At Newport. His tenure with Riverside was interesting. Serenade, his debut as a leader on Riverside, was preceded by a feature on Thelonious Monk’s Brilliant Corners in 1956. It was followed by Duke With A Difference in July ’57, a gem of an album, featuring mates from the Duke Ellington band including Johnny Hodges, Paul Gonsalves and Billy Strayhorn and, as the title suggests ironically, without Duke Ellington. He would add a couple more guest roles on Riverside such as Jimmy Heath’s Really Big and Johnny Griffin’s White Gardenia, but the most notable album is his own 1958 album In Orbit with Thelonious Monk, which is the only album including Monk as a sideman and set the standard of the use of flugelhorn in jazz.

The late Orrin Keepnews, label boss of Riverside together with Bill Grauer, looked back on a number of favorite releases a number of years ago, as can be seen on YouTube here. Serenade, Clark Terry’s second foray in small ensemble jazz after EmArcy’s Swahili, was among them, representing a masterstroke of bringing together Terry with the small ensemble hot shots of the day: “I always refer to Terry as Mr. Pulled Together. He is so tremendously talented, a nice guy, and he had that big band discipline in his life. (…) It was a very relaxed, and therefore, creative atmosphere. If you bring together musicians who have in a sense been rehearsing for years by playing with each other at lots of opportunities, that’s a very good way to get around that problem (of short rehearsing time)…”.

With a distinctive tone like Terry’s, brassy, virile, tart and full-ringing, consisting of a festive, good-humored quality, the equilibrium between calling-the-children-home and chasing-the-kids-away neatly in check, contrast with the other horn is assured. In comes Johnny Griffin, maybe not such a fast gun as one always assumes, fast, yes, but on this session intent on subtle conversations. Their ensembles sparkle, lock tight during uptempo bop tunes like Charlie Parker’s Donna Lee, Terry’s Boomerang and Serenade To A Bus Seat. It would be obvious to assume that the latter’s title alludes to the bus seat Rosa Parks bravely took on December 1, 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama. Her arrest led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott from Reverend Martin Luther King, a painful yet effective protest that eventually led to desegregation in the state’s public transport system. Clark Terry was from St. Louis, Missouri, where the NAACP protested against segregation in war factory jobs, a case it won through Shelly vs. Kraemer in the US Supreme Court, a feat Terry surely must’ve been conscious of, having been a bandsman in the Navy during WWII. That scenario sees Terry’s jubilant trumpet doing a good job of honoring Ms. Parks, Martin Luther King and the others who’d made the boycott possible. But it’s more prosaic. The liner notes explain that the title refers to the tiresome days Terry spent in the band bus of Basie and Ellington. Still no shortage of hardships along the road in The South though, as far as racism is concerned, lest we forget.

For Griffin and Kelly, Serenade represented their first appearances on the Riverside label.

The typical hard bop set of Serenade benefits from variation in the order of soloing, for instance during Donna Lee, when Griffin takes first cue and Terry follows trading fours with Philly Joe Jones. Not a pedestrian phrase in sight, the session cooks and runs remarkably smooth, courtesy of Griffin, the tasteful Paul Chambers, who had the kind of intuitive bass genius few possessed at that age, Philly Joe Jones (one rarely hears a session involving Philly Joe Jones that isn’t gutsy and fiery!) and Wynton Kelly, whose balanced, hip and barrelhouse-y lines of the title track are a treat. The leader, Clark Terry, enlivens the I-Got-Rhythm-changes of Boomerang with phrases that dance naughtily from mid-to upper register. It’s a virtuosic, happy tale and the originality is enhanced by the delicious, sustained notes in between. Terry stresses the cooperative spirit during the easy-flowing mid-tempo Digits, ad-libbing behind Griffin and calms the stormy weather that Griffin set in motion during Serenade with just a few peaceful stretch of notes, only to regain steam for the finale, getting into the fast lane with a spontaneous wail.

Gutsy calmness also during Stardust, a sign of the exciting style of Terry, diamond in the rough with a heart of gold. He’s a bluesman too, playing poker with notes veering from high to low and back. Boardwalk is the album’s blues line with a New Orleans feel and once again Clark Terry is like honey and mustard seeping through the walls of doom, no stopping it, the redeeming quality of Terry’s blues, a blues perhaps only mildly sardonic, always residing at the forefront. Down by the Riverside, his blues resembles that of his (and everybody’s) great ancestor, Louis Armstrong.