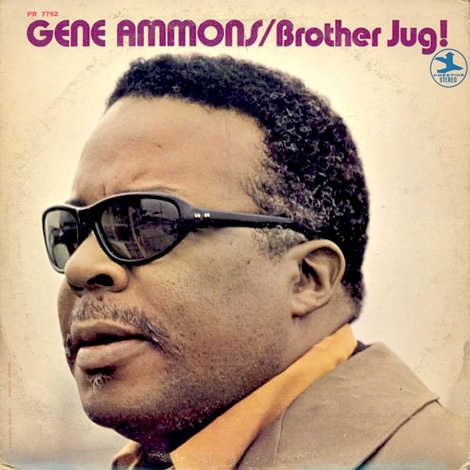

As if nothing had happened, Gene Ammons resumed his place in the Prestige roster after his seven-year long stint in jail and delivered four consecutive big-selling albums in 1969/70. Brother Jug is the second in line.

Personnel

Gene Ammons (tenor saxophone), Sonny Philips (organ), Junior Mance (piano), Billy Butler (guitar), Bob Bushnell (bass), Bernard Purdie (drums), Frankie Jones (drums), Candido (congas)

Recorded

on November 10 & 11, 1969 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7792 in 1969

Track listing

Side A:

Son Of A Preacher Man

Didn’t We

He’s A Real Gone Guy

Side B:

Jungle Strut

Blue Velvet

Ger-Ru

“Jug” was a nickname cast upon Ammons by singer and bandleader Billy Eckstine, whose band Ammons was part of in the mid forties, like so many future modern jazz giants as Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt. One day the band checked out new hats in a store. When Eckstine found out the enormous hat size of Ammons, he blurted out: ‘You jug-head motherfucker!’ The name, shortened to “Jug”, stuck. Shortly after, Ammons had his first big-selling song with 1947’s Red Top. The ballad My Foolish Heart, which had been in the book of Eckstine’s band, was next, a smash hit in 1951. The Prestige albums of Ammons sold well, especially 1960’s Boss Tenor, which spawned the popular Canadian Sunset, and 1962’s Bad! Bossa Nova. At that time, Ammons had become a heroin addict. Already having done stints in jail in the fifties, now the law put him away not only for possession but also selling narcotics, a sure sign that Ammons was abused as a symbol of ‘the degenerate, black musician’. He had to put up with a staggering seven-year sentence.

During those years of 1962-69, Prestige kept his name in the spotlight as best as it possibly could, releasing a number of albums with material from the vaults. Nevertheless, upon the release of Ammons from jail in 1969, the label was curious if the big-toned melodist could still deliver. The answer was affirmative with a capital A. Ammons had honed his chops in prison. The homecoming concert at Chicago’s Plucked Nickel in the fall of ’69 (the liner notes say) was a succes, the following gigs in Detroit, Baltimore and Philadelphia likewise. New York? No, Ammons wasn’t allowed to play in the Big Apple. A bunch of bureaucrats from the liquor board kept “Jug” out of town. Except for the studio of Rudy van Gelder, where Ammons recorded the well-received The Boss Is Back! and, subsequently, Brother Jug! and The Black Cat!. In between, Prestige released a live album with Dexter Gordon, The Chase!.

Meanwhile, the health of Ammons had detoriated considerably. Ammons passed away in 1974 at the age of forty-nine. They dug for “Jug”. At his funeral Sonny Stitt, whom Ammons had been associated with regularly throughout his career, played My Buddy. One of the best friends of Ammons, tenor saxophonist Prince James, also performed. James is featured on Brother Jug as well, on the last track of the album, Ger-Ru, which also includes Junior Mance, the pianist who’d been part of an early Ammons group.

The rest, however, consists of an organ combo including organist Sonny Philips and one of Prestige’s house rhythm sections of bassist Bob Bushnell and drummer Bernard Purdie. Solid groove music assured. The loose, tough-as-nails version of Son Of A Preacher Man is a ringer, while the flagwaving shuffle blues He’s A Real Gone Guy, a song from r&b singer Nellie Lutcher, conjures up images of loved ones leaning against the wall, drowning each other with drunken, smeary kisses. Every Gene Ammons album of the late sixties and early seventies has a stand-out track. On Brother Jug, it’s Jimmy Webb’s Didn’t We, a ballad that finds Ammons at the top of his unsurpassed, unique game of level-headed drama. Soon, as Ammons would grow more ill, his form would understandably falter. But for the moment, “Jug” was back at the forefront of entertaining and hi-level soul jazz.

Scroll down on the Spotify link to listen to most of the Brother Jug album. Well, The Boss Is Back is also pretty swell.