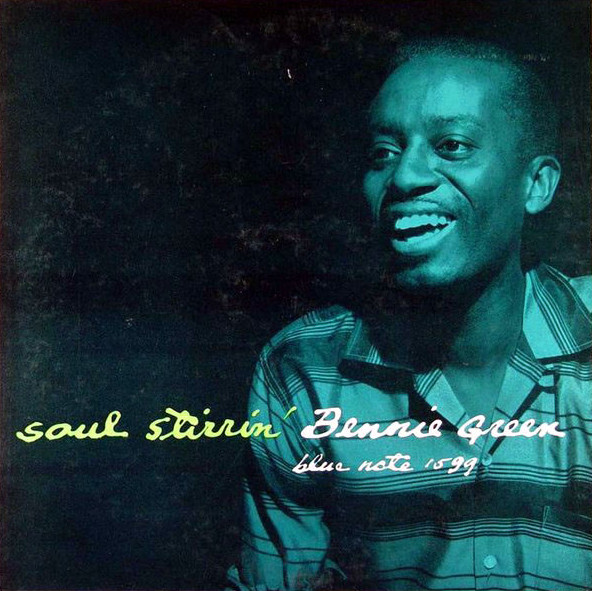

Of the invariably soulful albums from trombonist Benny Green, Soul Stirrin’, with the heavyweight line up of Gene Ammons, Billy Root, Sonny Clark and Elvin Jones, is arguably his finest effort.

Personnel

Benny Green (trombone), Gene Ammons (tenor saxophone), Billy Root (tenor saxophone), Sonny Clark (piano), Ike Isaacs (bass), Elvin Jones (drums), Babs Gonzalez (vocals A1, A2,)

Recorded

on April 28, 1958 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 1599 in 1958

Track listing

Side A:

The Cooker

Benny’s Back

Bossa Rocka

All Of Me

Big Fat Lady

Side B:

Benson’s Rider

Ready And Able

The Borgia Stick

Return Of The Prodigal Son

Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid

Benny Green is like that friendly uncle who always takes you aside at a family gathering, stuffing a couple of bucks into your pocket,

‘here kid, go buy yourself some candy.’ Green’s playing is accessible, uplifting, his phrases smack of smoke-filled back rooms, where burly whisky drinkers throw dirty jokes to the other end of the card table. His altogether very deft, modern style retains a lurid sense of old-timey swing, which places him at the other end of the spectrum opposite pioneer J.J. Johnson. His tone is tart, a lovely blast of fresh air.

By 1958, Green’s experience consisted of a decade spent in the bands of Earl Hines and Charlie Ventura. He had worked and recorded with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Sonny Criss, Hank Mobley and Randy Weston. Green was up for his second Blue Note album, following Back On The Scene and a slew of releases on Prestige onwards from 1951.

Not only did Green have aboard Ammons, Root, Clark, bassist Ike Isaacs and Jones, the bop poet and songwriter Babs Gonzalez also put his best foot forward, providing two melodies. Throughout the album, there are ample examples that justify the title. It’s a spirited, blues-drenched affair. There’s the sparse, precise riffing behind the soloists in We Wanna Cook, an uptempo, twelve-bar blues swinger, reminiscent of the Count Basie cookers, and also marked by Papa Jo Jones-style drumming by Elvin Jones. The same procedures – saxes spurring on trombone – mark the title track, absolutely the best tune of the album, a heated Blues March-type groove, albeit a bit slower. Babs Gonzalez hums the melody, the soloists take off, Gene Ammons especially commanding, on top of his game, blowing long wailing notes, coupled with sparse, melodic bop figures, a wall of sound from The Boss.

Gonzalez’ Lullaby Of The Doomed, Round Midnight-ish, is a breather. B.G. Mambo’s fat-bottomed theme jumps and jives, but turns into a rather pedestrian, straightforward 4/4 rhythm. Sonny Clark’s introspective side comes to the fore in Lullaby, his accompaniment on the album is spicy, he turns a beat here, injects a persuasive bass note further away from the sequence there, continuing to hold momentum all the way. Perhaps the mutual understanding of Green, Ammons and Root, who played together earlier in their careers, contribute to the album’s coherent soul groove. Billy Root, rather the mystery man of this set, a great, hard-swinging player, had a more imposing career than most people probably realize, most of the time spent as a sideman. He played with John Coltrane, Clifford Brown, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Stan Kenton, Lucky Thompson, Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Dizzy Gillespie and many others. Check out an enlightening interview of the candid Root with guest writer Gordon Jack on the great Jazz Profiles website of Steven Cerra here.

When listening to Black Pearl, you will notice that it closely resembles Black Pearls – with the added ‘s’ – from John Coltrane’s album Black Pearls. Soul Stirrin’ was recorded on April 28, 1958. Black Pearls – released as a profitable afterthought by Prestige in 1964 when Coltrane had long since moved to Atlantic and Impulse – is recorded on May 23, 1958. So Bennie beat ‘Trane to a month. The liner notes to Soul Stirrin’ say: ‘The program is completed with Black Pearl penned by sax man Bill Graham.’ However, Coltrane’s album credits not Graham but John Coltrane as composer. Did Coltrane nick a tune? Aficionados on the in-depth Organissimo website suggested that Graham’s credit got lost, it was then registered as unknown, and subsequently assigned to Coltrane. Apparently, Coltrane remembered the nice melody, picking it for that wonderful session with Donald Byrd, Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Art Taylor. Organissimo adds the fact that the tune is registered to Graham in The Coltrane Reference, the Bible of Coltrane facts. Recognition after all for Bill Graham, born 1918, a relatively unknown saxophonist who warrants more than a few words in another time and place. To be sure, Black Pearl is another one of the tunes making sure Soul Stirrin’s a keeper.