A year after the passing of Charlie Parker, the influential bop baritone saxophonist Serge Chaloff delivered his best album, Blue Serge.

Personnel

Serge Chaloff (baritone saxophone), Sonny Clark (piano), Leroy Vinegar (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Recorded

on March 14 & 16, 1956 at Capitol Studio, Los Angeles

Released

as T-742 in 1956

Track listing

Side A:

A Handful Of Stars

The Goof And I

Thanks For The Memory

All The Things You Are

Side B:

I’ve Got The World On A String

Susie’s Blues

Stairway To The Stars

How About You?

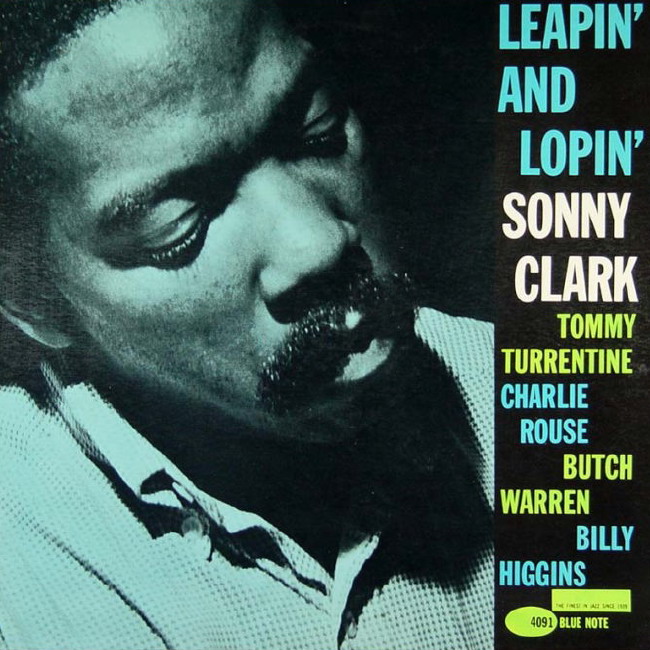

Parker’s redefinitions of the jazz language represented nothing less than an earthquake and certainly also bedazzled Serge Chaloff, who was born in Boston in 1923 from parents who were music teachers, with father Julius serving as pianist in the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Chaloff, who passed away in 1957, came up through the groups of Boyd Raeburn, Woody Herman (as part of the acclaimed Four Brothers reed section of the Second Herd), Georgie Auld, Jimmy Dorsey and Count Basie. His other influence beside Parker was baritone sax pioneer Harry Carney, longtime member of the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Both influences shine through on Blue Serge, Chaloff’s album that’s appropriately named after Duke Ellington’s composition, with a nod to the very blue Serge. The influences are incorporated into Chaloff’s remarkably fecund style, a style that locks tight with the alert, cookin’ Philly Joe Jones, the big-toned Leroy Vinegar, all-round bass class act and particularly exquisite as a ‘walker’, and Sonny Clark, master of long, horn-like lines and varied rhythmic placement.

Hi-level company: Jones on the brink of his defining role in the First Great Quintet of Miles Davis, embryonic vistas of Cool Struttin’ in the background of Clark’s mind, no other horn except baritone, Chaloff pulling it off as a distinct voice and stylist with graceful fluidity on the baritone saxophone, a feat that speaks volumes about the man’s authority. Chaloff’s sinuous, propulsive lines dance through a set of fast bop, ballads and medium tempo swingers on familiar changes. He’s a captivating balladeer that speaks to a lover both with sweet, breathy whispers and husky, sardonic, slightly vibrating comments on the one hand, a virtuoso who travels with deceptive ease through fast-paced burners on the other hand.

And whether it’s the loping tempo of A Handful Of Stars or the quicksilver pace of Al Cohn’s The Goof And I, instead of being led by it, Chaloff directs the flow of the quartet. Blue Serge is such an excellent session because that conductive quality is a talent that Chaloff shares with Clark, both possessing acute melodic rhythm and effortless flow. The mark of great players, particularly coming to the fore in receptive surroundings, and a mark we perhaps most of the time grasp intuitively, then finding it a marvel.

Chaloff was a major innovator on the baritone saxophone, paving the way for Cecil Payne, Pepper Adams and modern-day greats like Gary Smulyan, but his reputation is hampered by a concise discography, the direct result of the man’s addiction to drugs and the resulting struggles of maintaining proper work relations. Allegedly, Charlie Parker advised his disciples time and again to stay away from the stuff, most of the time to no avail, certainly in the case of Chaloff, a notorious user and rebel rouser. How tragic that, once Chaloff kicked the habit in 1957, having returned to his native city of Boston, he was diagnosed with spinal cancer and passed away on July 16. Regardless, Chaloff left us a magnificent piece of bari playing that is still fresh after all these years.