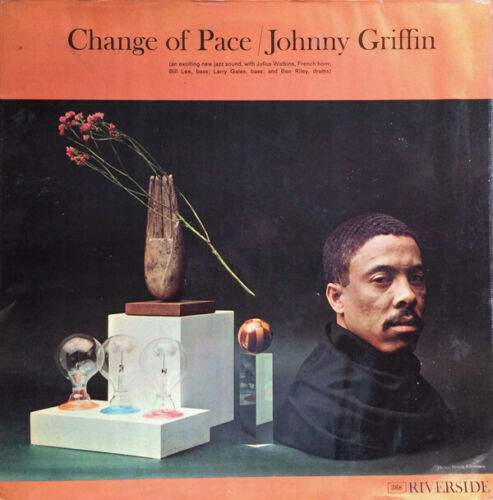

The Little Giant broadened his horizon on Riverside Records.

Personnel

Johnny Griffin (tenor saxophone), Julius Watkins (French horn), Larry Gales & Bill Lee (bass), Ben Riley (drums)

Recorded

on February 7 & 16, 1961 in New York City

Released

as RLP 368 in 1961

Track listing

Side A:

Soft And Furry

In The Still Of The Night

The Last Of The Fat Pants

Same To You

Connie’s Bounce

Side B:

Situation

Nocturne

Why Not?

As We All Know

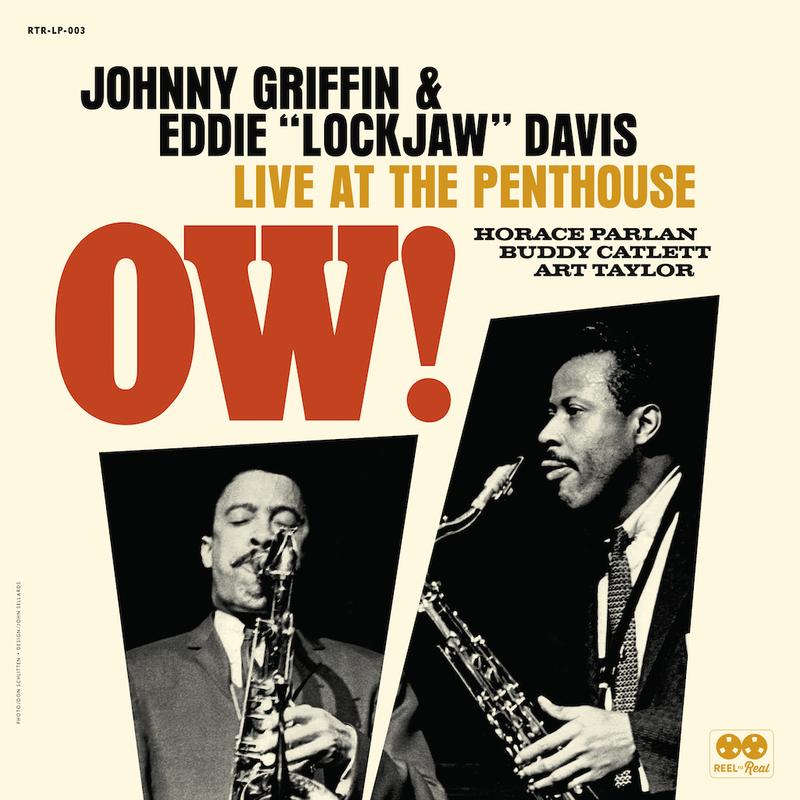

As far as unity of vision, style, sound and sleeve design is concerned, Blue Note of course is the max. But Riverside had tastes of her own as well. Regardless of occasional complaints of vinyl pressings by monophiles and stereophiles, Riverside’s value as a front-line jazz label, largely due to founder Orrin Keepnews, is widely acknowledged. Take the case of Johnny Griffin. The bop and hard bop tenor saxophonist traveled from Argo and Blue Note to Riverside, for which he recorded a series of diverse albums between 1958 and ’63. Part of those were as co-leader on subsidiary Jazzland with his hard-blowing tenor colleague Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis.

So, on the one hand, Griffin swung straightforward and hard, occasionally with “Jaws”, and on the other hand explored his fascinations in agreement with Keepnews, who was already a concept-minded boss. Keepnews had started Riverside as a company of traditional jazz compilations, provided history of jazz narratives on wax and let Thelonious Monk debut on his label with repertory of Duke Ellington – controversial and surprising move dividing Monk geeks to this day. Griffin’s records were top-notch. The folk song hodgepodge of The Kerry Dancers and gospel-drenched The Big Soul Band are considered Griffin classics. Studio Jazz Party is a hot little date – here Keepnews repeated the idea of recording artists in the studio in the presence of a small live audience, which had proved extremely successful in the case of The Cannonball Adderley Quintet’s In San Francisco in 1959.

Change Of Pace is another odd man out. Tasteful dish. Safe to say, like a refined bouillabaisse from Marseille. The recipe consists of Griffin’s tenor saxophone, Julius Watkins’s French horn, Larry Gales and Bill Lee’s upright basses and Ben Riley’s drums. (Gales and Riley played on Griffin/Lockjaw Davis records and would eventually become the rhythm section of Thelonious Monk from 1964-67) Pretty unusual ingredients that flavor Change Of Pace’s refreshing and sophisticated repertoire. Excepting Cole Porter’s In The Still Of The Night, which flows gracefully in spite of its breakneck speed, the excellent songwriting is on account of Griffin, while Watkins, Bill Lee (film director Spike Lee’s father) and Consuela Lee (no relation!) each provided one tune.

The absence of piano makes the music breathe with peppermint breath. The combination of arco and bowed bass fills in harmonic gaps equally effective as Watkins’s soft-hued alternate lines behind Griffin’s supple and strong tenor. As a rule, Griffin is fiery, playing as if he devoured a couple of red hot chili peppers. But here he has found a particularly strong balance between bop and lyricism, exemplified very well by Soft And Furry, a remarkably tender song and irresistible Griffin classic. The restrained and fluent approach of prime French horn player Julius Watkins, who was rivalled only by David Amram in the 50s, reveals a true master at work. At once bossy and vulnerable, Watkins plays as if he’s constantly serenading his lover.

The sound palette of Change Of Pace is curiously enchanting and mesmerizing. A warm bath. Fulfilling, akin to the feeling you have when letting yourself fall down on a hotel bed after a long walk in a strange and beautiful city. It sounds as hip and modern today as it did in 1961.