Saxophonist Gideon Tazelaar, 19 years old, is one of Holland’s major jazz talents. Leaving his options open for the next five years, Tazelaar at least is positively sure of one next step. “Next year, I’m going back to New York.”

Tazelaar stayed in New York once before in 2015, joining sessions, held spellbound by the remaining legends of modern jazz like Harold Mabern, Jimmy Cobb and Jimmy Heath. “I saw Roy Haynes twice. That was magical. I’ve never seen anything like it. He played with his quartet plus Pat Metheny. But I only watched Haynes behind his drumkit. Everything he did was so spot-on. I was often wondering where he was, time-wise. But I’ve come to the conclusion that, really, what Haynes played

was the time. Somehow, Haynes

was the music. He went into a tapdance routine, which, astonishingly, revealed the entire jazz tradition. And of course it was special to see someone perform who goes way back to Charlie Parker, Monk, Coltrane… Even to Lester Young.”

With a hesitant timbre in his voice, as if ashamed of his good fortune: “And I had breakfast with Lee Konitz. He’d been my teacher once in Germany and said to call me whenever I was in town. That was awesome. We were at his place. I got a little quiet… But he kept talking, so that was perfect! Konitz said that he felt uneasy recording Motion, because it was his first encounter with Elvin Jones. But in hindsight he thought the results were rather satisfying… I’ve learned lots of things from Konitz. Musical stuff, because he’s a genius, but also about attitude. He doesn’t seem to have an all-encompassing explanation of his musical choices, except that they develop from a search for beauty. He really gives you the idea that the purpose is to follow up on what you love and dig deep into that well.”

“I’m really looking forward to another stay in New York. I will be going for about one year and maybe study at some music college, check out older musicians. Men like Reggie Workman and Charlie Persip still teach. The division between styles is less astringent than here. I’ve noticed this during some sessions with Ben van Gelder and American colleagues, they blew me away playing stuff ranging from blues to Bud Powell to avant-leaning compositions. In The Netherlands, people sometimes encounter me as that supposedly ‘promising musician’. They are friendly, responsive. That’s ok, for sure, people have helped me out a lot. But I haven’t really been at the bottom of the ladder, you know what I mean? And I think it would be beneficial to my musicianship if colleagues kick me in the butt now and then. And they will in New York, regardless of my age, I’m sure! I’m looking forward to it.”

Meanwhile, Tazelaar performs as much as possible. “I try to do my bit of study as well. My mindset changes continuously, so I press myself to study with focus. I like so many things, therefore I have to structure things to really get to the heart of the matter and not be distracted. I’m making schemes for two months in advance.”

Tazelaar grins, his downy, dark-brown moustache twists. He pulls himself from his couch, finds a notebook between the rubble on his desk, sits down and proceeds to read his upcoming scheme. If anything, an intriguing hodgepodge of activities. Among other things, Tazelaar is going to practice clarinet again, learn a Bud Powell solo on piano, read the biography of Sidney Bechet, finish an original Tazelaar tune, study the theory of Schönberg, harmonize chorals in Bach style and, last but not least, learn 3 solo’s of Frank Trumbauer, Bix Beiderbecke and Louis Armstrong each. Monomania. Eagerness. A young man enthralled by the beauty of America’s sole original art form as well as the works of classical composers who often were admired by the jazz legends.

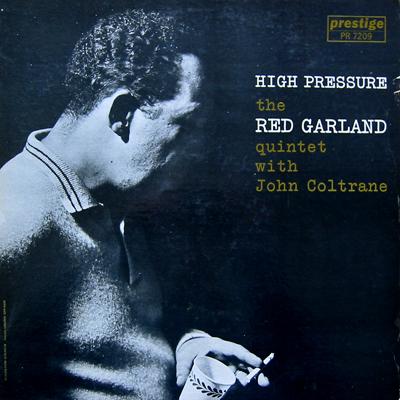

Recognition for Tazelaar has come early. Already playing saxes as a kid and adding clarinet in the process, Tazelaar has been in the limelight ever since. He played at The Concertgebouw at the age of 8, enrolled at the Conservatory of Amsterdam when he was 14, passing maxima cum laude at 18. If he may choose to, Tazelaar can put a nice rack of prizes on his mantle and has been a regular fixture in the club circuit and at the North Sea Jazz Festival. Sitting under a framed portrait of John Coltrane, the eyes of the bright college student-type Tazelaar twinkle when looking back upon his contribution to a tenor summit at the Bimhuis last March, including Rein de Graaff, Eric Ineke, Eric Alexander, Sjoerd Dijkhuizen and Ferdinand Povel. “So inspiring to play with the elders. And especially great to share the stage with Ferdinand, who has been my teacher for a long time. He teached me a lot just by talking about jazz, and especially about harmony. He plays so beautifully. I think I nicked quite a few of his phrases.”

Asked about his playing style, the contemplative, even-tempered Tazelaar is cautious to ill-define matters. He patiently weighs his words on a scale, much like the way a thrift store owner would count the coins that a bunch of candy-buying kids have scattered on the counter. Lots of ‘umms’ and ‘aaahs’. The sound of a brain cracking. “Tough question. I don’t think I play in one style. I experience it as versatile, depending on the people I play with. It puts the big picture of a group in perspective, I don’t feel the need to deliberately go against the grain in a group, style-wise. Arguably, it’s all part of my development. I might one day stick to something that feels destined to be played. In general, I have my influences as well, of course.”

Aside from Povel, Tazelaar is fond of saxophonist Benjamin Herman, having thrown himself headlong into the weekly sessions at Amsterdam’s De Kring. “Basically, I’m a very critical and self-critical guy. Genes, I guess. That’s ok, critique’s a constructive asset. But it tends to stress negative aspects as well. Benjamin focuses on good things, he’s able to find interesting, quirky aspects in different kinds of music. That’s positive. And better for your mental health.”

Tazelaar has been picking some positively quintessential influences at an early age. “I’m listening to a lot of classic bop and hard bop saxophonists, but up until now I’ve always come back to my main men: Bechet, Parker and Coltrane.”

“I’m always interested in the transitional periods in the careers of musicians. Those recordings of Bechet in France in the late forties are great. (Tazelaar refers to Bechet’s May 1949 recordings with either the Claude Luter Orchestra or Pierre Braslavsky Orchestra) He’s playing New Orleans-style, of course, but hints at things to come as well. He would be an influence on Coltrane.”

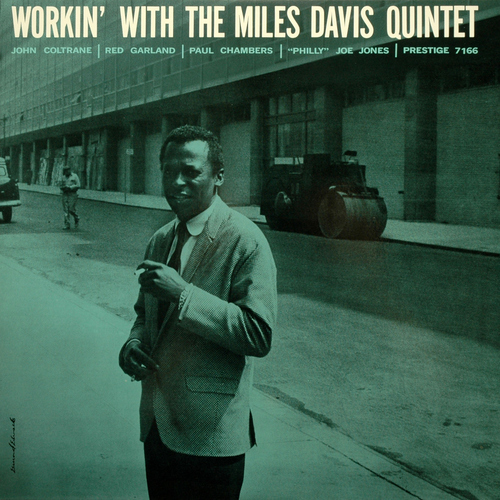

“I really like both early and late Coltrane. Early or late, the integrity and inspiration are always there. Lately I’ve been listening to Coltrane with Miles Davis in 1960, near the end of Coltrane’s stay with Miles Davis. There’s this live version of ‘Round Midnight, it was on bootlegs I think. Coltrane goes from one extreme to the other, but keeps referring to the melody in between, it’s fantastic.”

“Parker’s playing on Dizzy Atmosphere (February 28, 1945, Savoy MG12020, FM) is also a good example of tension between old and new. Swing and bop, in this case. There’s this swing rhythm section including bass player Slam Stewart (and Clyde Hart, Remo Palmieri and Cozy Cole, FM) that swings like mad. Parker and Gillespie are inventing the bop language on top of it. But the thing is, Parker blends well with that old style, because he lived in that period as well, naturally. He knew where it was at. In these performances, Parker constitutes the best of two worlds, he fits.”

Gideon Tazelaar

Gideon Tazelaar (Hilversum, 1997) has been performing from age 8, appearing at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Prinsengracht Concert. Since his early teens, Tazelaar has been a sought-after player, performing with the Dutch Jazz Orchestra and the Jazz Orchestra Of The Concertgebouw as well as at The North Sea Jazz Festival, and has been cooperating with, among others, Benjamin Herman, John Engels, Peter Beets, Ben van Gelder, Dick Oatts, Eric Alexander and, in the summer of 2016, organist Lonnie Smith. Tazelaar won the Composition Award of NBE in 2006, the Prinses Christina Jazz Concours in 2012 with his quartet Oosterdok 4 and the Expression Of Art Award in 2016. Nowadays, Tazelaar regularly plays with his Gideon Tazelaar Trio, which includes bass player Ties Laarakker and drummer Wouter Kühne.

Check out Gideon Tazelaar’s website here.