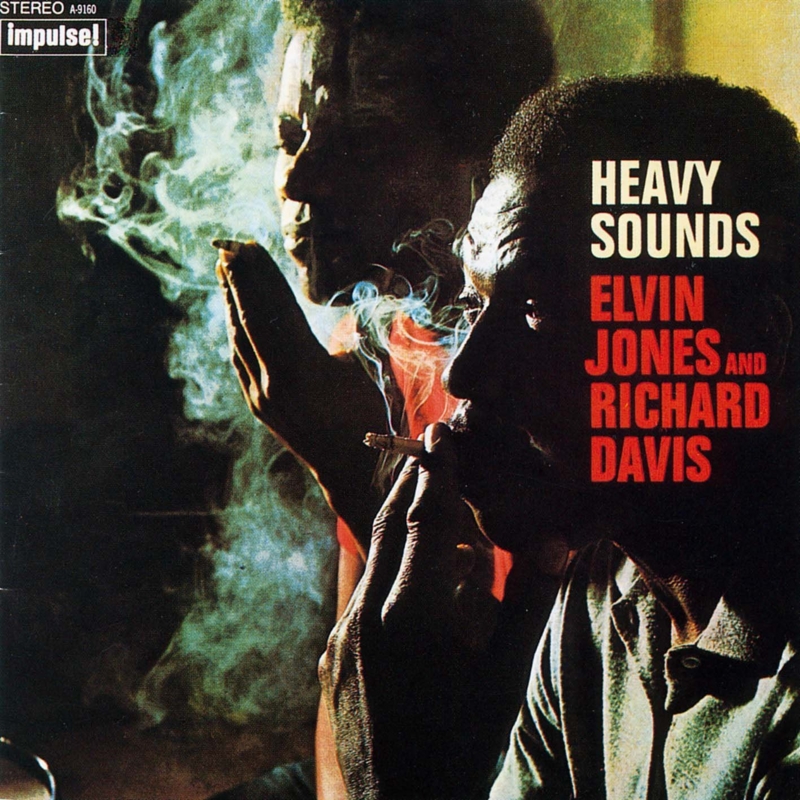

Heavy sounds and heavy smoke rings. Elvin Jones and Richard Davis obviously enjoyed each other’s company. Above all, they’re having fun on an extremely high musical level.

Personnel

Elvin Jones (drums, guitar B2), Richard Davis (bass), Frank Foster (tenor saxophone A1-3, B1, B3), Billy Greene (piano A1, A3, B2, B3)

Recorded

on June 19 & 20, 1967 at RCA Recording Studio, NYC

Released

as AS-9160 in 1968

Track listing

Side A:

Raunchy Rita

Shiny Stockings

M.E.

Side B:

Summertime

Elvin’s Guitar Blues

Here’s That Rainy Day

Amonth later, the moods darkened considerably. Heavy Sounds was recorded on June 19 & 20, 1967. John Coltrane, Elvin’s associate from the legendary, groundbreaking John Coltrane Quartet, passed away on July 17, 1967. During his tenure with Coltrane, Jones had already recorded occasionally. Elvin! (Riverside 1961) and Dear John C. (Impulse 1965) are notable albums. In 1966, Jones allegedly felt uncomfortable with Coltrane’s new rhythmic settings that included drummer Rashied Ali and quit the band.

Enormous potential besides the magnitudinous presence of Elvin Jones. Richard Davis is one of the most virtuosic bassists of the classic jazz era, arguably the most proficient. A brilliant musician who also took care of business in symphony orchestras, having performed with Igor Stravinsky, Pierre Boulez and Leonard Bernstein. A versatile player who was an asset on straightforward jazz dates but shined particularly bright on adventurous recordings like those of Andrew Hill (Black Fire, Judgment, Point Of Departure), Eric Dolphy (Out To Lunch), Kenny Dorham (Trompeta Toccata) and Jaki Byard. (Freedom Together!) and who likes to stray from the root, incorporating mesmerising sliding effects in the process. Other giants of bass like Ray Brown and Paul Chambers may hold the advantage over Davis as far as the pocket and glueing together the different sounds of a group is concerned but flying through changes with an immaculate beat certainly was made look easy by the Chicago-born bassist. The following years, Davis was part of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra (1966-72), built up a prolific solo career and would continue to be one of the most sought-after bassists both in mainstream and avantgarde jazz, even extending his playground to popular music, featuring as session musician for, among others, Van Morrison (Astral Weeks), Paul Simon and Bruce Springsteen. (Born To Run) Heavy cat, heavy workload.

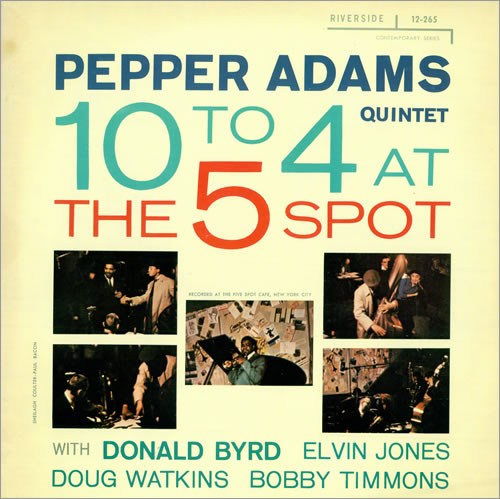

There’s Frank Foster. One of the uncrowned kings of the tenor saxophone. Sometimes, to put the value of a musician in perspective, it’s enlightening to let a knowledgable fellow musician speak. In Frank Foster’s case, the Dutch drummer Eric Ineke, who saw Foster perform with (one of his major drum heroes) Elvin Jones at the legendary Five Spot Cafe in 1966 and played with Foster a number of times. Ineke offers a favorable judgement of the tenorist and composer in his book of conversations with Dave Liebman, The Ultimate Sideman: “The way Frank could build up the solos… Very compositional and long. (…) He was like ‘Trane: so creative, he could never stop! He really could build his solos from Lester (Young, FM) to Trane. There is so much knowledge in his playing (…) On the road he was always writing and arranging for big bands. A very high level cat and one of the truly great jazz tenor players.”

Davis, Foster, ok. But who’s Billy Greene? Heavy Sounds is his only known recording. A pseudonym? Whitney Balliett’s profile of Elvin Jones in The New Yorker of May 18, 1968 reveals that Billy Greene was Elvin’s pianist at the time. So at any rate, Billy Greene was, well… Billy Greene. Anyone out there with the goods, speak up!

Heavy Sounds is a peculiar but delicious hodgepodge of styles. Elvin’s Guitar Blues (yes, Elvin on guitar) is vintage country blues, a basic 12-bar tune that could be tossed away as the one filler cut of the album, were it not for Frank Foster’s smokin’ tenor. Shiny Stockings, Foster’s famous instant-standard that he wrote for the book of Count Basie, whose orchestra Foster was a part of in the mid-fifties, is a surprise, but then again, not so much, since, firstly, it is an unbeatable, beautiful tune that sits well on any album (and many albums) and, secondly, is transformed by the group from the frolic swing evergreen into a improvisational gem, while retaining a definite sense of swing. The powerful work with the brushes of Elvin Jones is striking.

The moody ballad Here’s That Rainy Day, starring the full-bodied tenor of Foster, and a concise, uptempo mover, Billy Greene’s M.E., are very enjoyable. Most arresting, however, are two pieces on side A and B that both stretch the eleven minute mark without letting up one bit. Opener Raunchy Rita is heavy sounding indeed. Run through the poly-rhythmic shredder of Elvin Jones, the original blues tune (with an elongated B-section) of Frank Foster becomes a special treat. Jones is enjoying an uplifting dialogue with his compadres, cautiously nudging Billy Green forward at first, who caps off lilting clusters of funky chords with Middle-Eastern flavored series of lines, and backing up Frank Foster with a sound carpet that develops multiple delicate accents into a state of near-kinetic frenzy. A primal force. (Makes me realise yet again that Jones was a prime influence on drummers like Mitch Mitchell, Jon Hiseman and Robert Wyatt and a major inspiration behind their riotious, press-roll shenanigans) Foster thrives, Foster laughs, Foster seems to state: ‘Hey, Elvin, dig this, you’re gonna love it!’ and forces a roaring answer out of Jones. Usually, it’s the other way around. The dame with the name of Rita probably dances on the table for much of her spare time and the sweeping arc of Foster’s big-toned, husky tenor phrases is perfect accompaniment of her front room fancies. Foster relishes both a Ben Webster bag and the kind of left-field story lines that advanced hard boppers like Joe Henderson and Yusef Lateef eagerly shook out of their sleeves in the mid-sixties. The tenorist throws in edgy twists and turns in the upper register for good measure.

Raunchy Rita reminds me a bit of Eddie Harris’ Freedom Jazz Dance. It’s basic, funky, danceable yet possesses an intriguing free vibe still fresh after all these years. Summertime reminds me of Summertime, yet in a wholly different manner one would expect. Gershwin’s warhorse is a fascinating duet between Jones and Davis. In Ashley Kahn’s book The House That Trane Built: The Story Of Impulse Records, Elvin Jones and Richard Davis explain how it came about by happenstance:

“It was one of those things Bob Thiele was doing at the RCA Studio on 22nd Street, and Larry Coryell was supposed to there, but didn’t show up,” explained Elvin Jones. “He was sick or something, and so Richard and I were there.” Richard Davis picks up the thread: “Bob said, ‘why don’t you guys just go ahead and start playing?’ I had always thought that perhaps one day I would play Summertime as a ballad with luscious strings, the harp, the flutes, and all the accessory instruments for flamboyancy. And as it turned out I played it with just Elvin Jones (laughs).” “So we just started fooling”, Jones said, “Richard using his bow, warming up basically. I asked him, ‘What’s that you’re playing?’ and he said, ‘Summertime’. So we kind of made a thing out of it, like a duet, tom tom, mallets and bow.” Davis: “No discussion, no editing, no plan… and I just thought there was some very brotherly thing about that particular piece.” Jones: “It was so good that they didn’t want to discard it. I said, ‘Look, Larry isn’t here, I should call up my band and have them come in…’” Davis: “Bob said, ‘Ok, why don’t you guys come back tomorrow and get somebody?’ Elvin got Frank Foster and Billy Greene.”

A revealing little jazz story not only about superb musical skills and responsive improvisation, but also about how great things happen when producers adress their own spontaneous, flexible personality traits. On impulse, so to speak.

Davis switches between dark, resonant or high screaming strokes with the bow and an amalgam of inventive statements supported deftly and gently by Jones. The first part of Jones is a delicate celebration of the melody, a balanced combination of toms, cymbal and, I presume, a ‘de-snared’ snare. As the tune progresses, Jones has somehow turned it into a jungle beat, dragging the beat, stretching the bars as if they’re sturdy stripes of rubber. Further stoking up the heat, Elvin accompanies his singular drumming method with buzzing, bear-like groans. Elvin is much like ye old steam engine locomotive that grinds his way up the hill. A tough climb but he’s gonna make it, and everything – from the steam clouds, whistle and crackling noise of the rails – adds to an already lively sensation. Elvin’s from the Mechanical Age, a time when stuff could be deconstructed and put together again, fixed. Iron’s alive. Plastic’s fake.

No plastic people on Heavy Sounds. But real people, searching for real sounds.