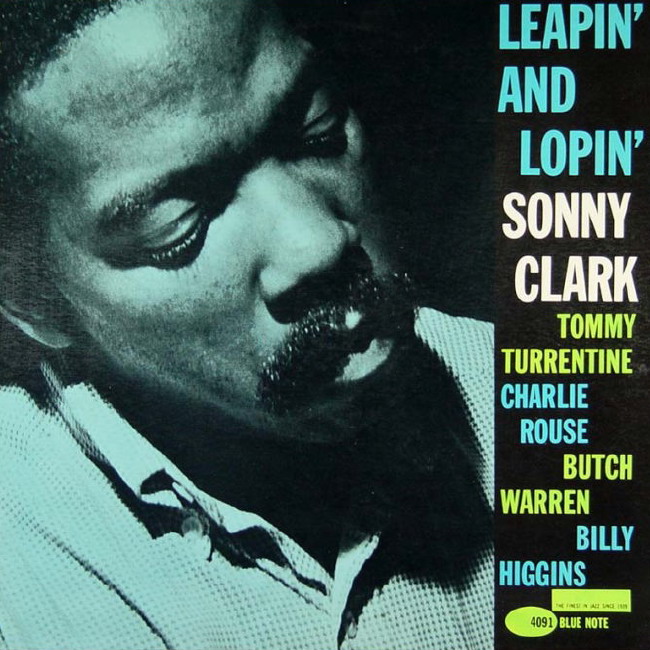

Find me a bummer moment in Sonny Clark’s discography and I’ll buy you a drink. But I won’t because it’s a fruitless search. One of the essential hard bop pianists, Clark had taste written all over him. His swan song as a leader, Leapin’ And Lopin’, includes some of his most enduring tunes and classiest performances.

Personnel

Sonny Clark (piano), Tommy Turrentine (trumpet), Charlie Rouse (tenor saxophone), Ike Quebec (tenor saxophone A2), Butch Warren (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded

on November 13, 1961 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 4091 in 1962

Track listing

Side A

Something Special

Deep In A Dream

Melody In C

Side B

Eric Walks

Voodoo

Midnight Mambo

Does it top 1958’s Cool Struttin’, Clark’s best known (and best-selling) album? A foolish question, perhaps. Brilliant Clark moments weren’t reserved for his leadership dates only but occured just as frequently when he appeared as a sideman for the myriad of fellow legends of the day, particularly for Blue Note, where Clark was a more than welcome pianist in his heyday of 1958-62.

Take his tremendously swinging and inspiring accompaniment and soloing on Dexter Gordon’s masterpieces Go and A Swingin’ Affair. Or that fabulous solo on Airegin from the sessions that would be released posthumously (for both of them) as Grant Green albums Nigeria (Airegin spelled backwards) and Oleo, wherein both musicians really get down with it. It’s a typical Clark mix of elegance and raw power.

I guess it’s this mix, steeped in the blues, that has kept luring musicians and incrowd into the Sonny Clark realm both during his lifetime and for decades thereafter. Clark, one of the most infamous jazz casualties, died from an overdose in New York City on January 13, 1963. To name but a few admirers, note that Bill Evans composed a touching tribute to Clark in 1963, the anagram NYC’S No Lark, and that John Zorn recorded Clark or ‘Clarkian’ tunes for years. 1985’s Voodoo is a well-known album of Zorn’s The Sonny Clark Memorial Quartet.

Also very attractive are Clark’s long, fluent lines that often stretch over bars extensively. Like those your hear in Leapin’ And Lopin’s third cut, Melody For C, a shuffle that swings both smoothly and intensely, all the while showing enough eccentricity to make you laugh and leap sideways.

In the uptempo Something Special, a very attractive melody that, not unlike a Horace Silver tune, benefits from effective use of stop time, Clark leaves plenty of space as an accompanist for Charlie Rouse and Tommy Turrentine to freely swing their way through the changes. The manner in which Rouse starts his solo, building on the melody, suggests the influence of Thelonious Monk, whose outfit Rouse had been part of since 1959. Voodoo is jazzified blues at its very best: intricate enhancements on the blues form coupled with heartfelt blowing. It’s the one track that would fit right in on Cool Struttin’.

The abovementioned tracks are accompanied by Deep Dream, a ballad that combines wry wit with pathos (including Ike Quebec’s breathy tenor), bassist Butch Warren’s quirky, intricate Eric Walks and Midnight Mambo, a buoyant Tommy Turrentine composition. They round off the most diverse album in the brilliant pianist’s book.