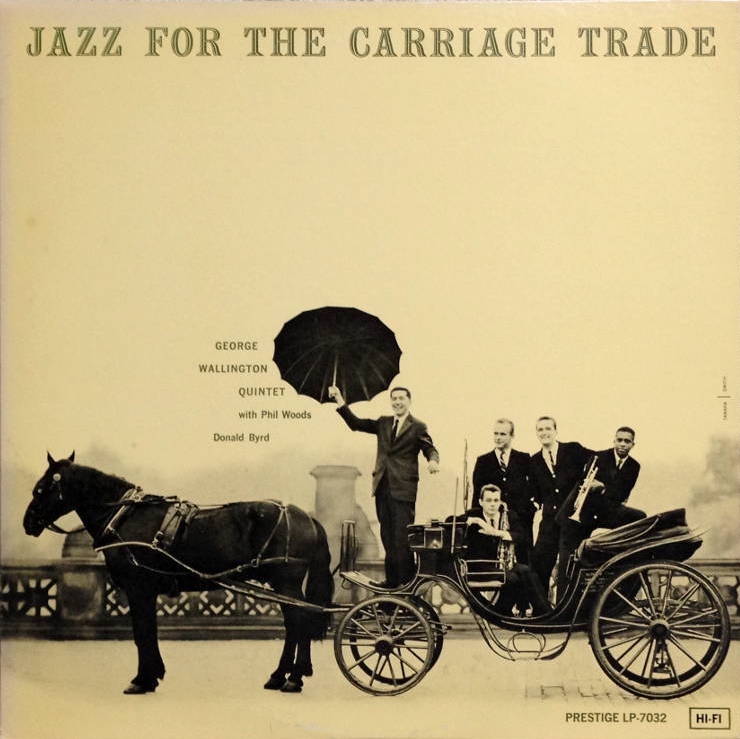

Pushing down stuff down the throats of the well-to-do is all fine and dandy but the true elite of course is Wallington & Co themselves.

Personnel

George Wallington (piano), Donald Byrd (trumpet), Phil Woods (alto saxophone), Teddy Kotick (bass), Art Taylor (drums)

Recorded

on January 20, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as PLP 7032 in 1956

Track listing

Side A:

Our Delight

Our Love Is Here To Stay

Foster Dulles

Side B:

Together We Wail

What’s New

But George

Here’s a rare bird, try to catch him and off he goes… What with the overwhelming presence of Bud Powell and Oscar Peterson and the constant introduction of sassy newcomers as Horace Silver and Sonny Clark, it isn’t particularly weird, if unfortunate, that George Wallington is rarely mentioned. He’s an interesting pianist, born Giacinto Figlia in Sicily in 1924, raised in New York City from 1925, a flashy dresser as a kid, which is why kids in the hood would shout, “hey, look at Wallington!”. Hence the switch from Figlia to Wallington.

An important contributor to the development of bebop in the mid-1940’s, Wallington played with Dizzy, Bird, Serge Chaloff, Allen Eager, Al Cohn and Gerry Mulligan. Wallington is noteworthy not just because he was a plainly exceptional pianist, but because the development of his style is contrary to that of most of his colleagues. Most everybody, of course, was hit by thunderbolt Bud Powell. It seems that the style of precursors as Earl Hines greatly influenced Wallington’s playing. Strong left hand bass lines, cross-rhythm and chunky and brittle phrases are dominant. While Powell is thunder and lightning, a kite surfer riding the waves, not falling once (when in top form and not marred by mental issues) with gusts up to force 8, Wallington is blue skies and fat cumulus clouds and a sneaky breeze that blows the hat from your head.

His interaction with the proto-typical ‘bombs’ from the drummer showcase a penchant for the percussive qualities of the 88 keys. Check out, for instance, his feature on Brew Moore’s Mud Bug from 1949 and Escalatin’ with Charles Mingus and Max Roach in 1952 (wild ride on down, bell boy’s going crazy). Lest we forget, Wallington was an excellent writer. Godchild, initially recorded on the eponymous Birth Of The Cool record by Miles Davis & Co, is his best-known composition, followed closely by Lemon Drop, which had a spot in the book of Woody Herman.

Paradoxically, when many colleagues started to look for an escape from the constraints of the bop changes, Wallington delivered some Powellesque records in the mid-1950’s. Here’s Busman’s Holiday from 1954’s Variations. Thereafter, Wallington peaked with a couple of original performances, suggesting the influence of Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols. This while still generally playing in a bop context, check out Ornitology from Leonard Feather Presents Bop from 1957, featuring Idrees Suliman, Phil Woods, Curley Russell and Denzil Best.

One of his best albums, Jazz At The Carriage Trade, features Wallington’s working quintet of newcomers Donald Byrd and Phil Woods, pal from the early bop days Teddy Kotick and Art Taylor. Lord Wallington put his sword on the shoulders of his bandmates, tapping each shoulder twice, to indicate that they had collaborated on a superb hard bop date. It’s smooth, it’s hot, it’s relaxed and propulsive.

Wallington’s use of space is striking, his hanging on a note like a kid on momma’s sleeve is rather enchanting and the occasional focus on black keys hypnotic. Subtle left hand lines crawl into the fabric of the quintet’s program. Whatever the pace, whatever the tune – Dameronia, Fosteronia, Gershwin and a couple of boppish originals make up for satisfying repertoire – there is something definitely ego-less about the way Wallington accompanies his men. Smart and stimulating.

Some of the best work of Woods, young Woods still, is to be found on Carriage Trade. Parker-ish and supple as honey dripping from a spoon. Donald Byrd is a bright and sassy teammate. A Prestige date that reveals good preparation. Excellent RVG soundscape.

A couple of years later, Wallington flew the coop. Apparently tired from the biz, the pianist got into air-conditioning, a family affair. Wallington eventually returned to the scene shortly in the mid-1980’s and recorded three solo piano records for Interface and VSOP.

Wallington passed away in 1993.