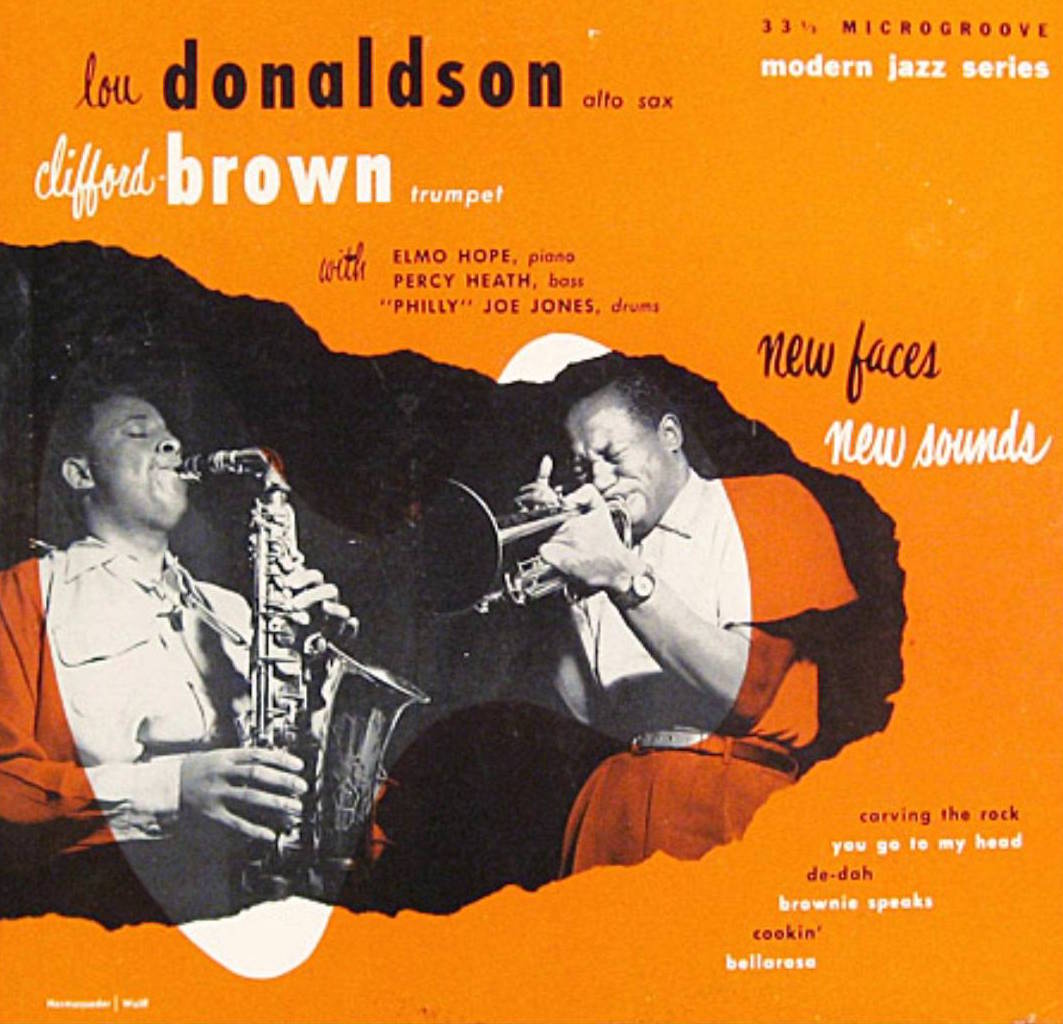

Lou Donaldson’s New Faces New Sounds plays a considerable part in the evolution of hard bop, not only for its introduction of future trumpet star Clifford Brown. As journalist Marc “Jazzwax” Myers suggested, something’s going on with Bellarosa, the last track of the Blue Note 10 inch, which was recorded on June 9, 1953.

Personnel

Lou Donaldson (alto saxophone), Clifford Brown (trumpet), Elmo Hope (piano), Percy Heath (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Recorded

on June 9, 1953 at WOR Studios, New York

Released

as BLP 5030 in 1954

Track listing

Side A:

Carvin’ The Rock

You Go To My Head

De-Dah

Side B:

Brownie Speaks

Cookin’

Bellarosa

Considering hard bop, you can’t get around alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson. The Charlie Parker-influenced saxophonist steered jazz into different directions twice during the fifties and sixties. Donaldson is best known by the general public for his commercial output during his second stint with Blue Note in the mid and late sixties, when he recorded a string of soul jazz and jazz funk albums that not altogether met the criteria of jazz snobs but remain popular to this day. Small wonder, because they distilled a juicy, crafty brew out of black contemporary music like boogaloo and James Brown. Although Donaldson’s ‘commercial’ jazz has its occasional superficial moments, I think it has been playing an essential role in keeping jazz lively and fresh for jazz buffs and attractive for newcomers who might otherwise be scared off by the so-called ‘difficult’ art form of jazz.

Earlier on, in the mid-fifties, Lou Donaldson’s intuition for what could give jazz a lift had been spot-on as well. Instead of recording frequently, Donaldson made miles on the chitlin’ circuit, drenching his modern jazz style with r&b, a move that reached out to the urban Afro-American community, coinciding with the remarkably classy taste that community had back then. As soon as Donaldson went back into the studio in 1957, he laid down the bluesy, hard-driving results on albums as Wailing With Lou and Blues Walk, as well as organist Jimmy Smith’s Jimmy Smith Trio + L.D.

The North Carolina-born altoist was part of the second generation of bebop players that followed the footsteps of Parker, Powell, Gillespie and Monk. Donaldson recorded with Monk as early as 1947. He played in the groups of Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver and Blue Mitchell in the early fifties and recorded with Milt Jackson in 1952. Then, on February 21, 1954, Donaldson appeared on the Art Blakey Quintet’s seminal Live At Birdland I & II, including Horace Silver and Clifford Brown.

The key figures of hard bop, or mid/late fifties mainstream jazz are Horace Silver, Art Blakey and Miles Davis. Horace Silver incorporated into modern jazz catchy (but very intricate) tunes imbued with gospel and blues feeling, Art Blakey the big beat on 2/4 and effective fills/bombs as opposed to interval-filled rhythm, (meanwhile introducing a host of young, future jazz stars) and Miles Davis the stress on expression (less is more) and dark-hued colours instead of a speedy flight through astringent changes. As early as the early fifties, Silver experimented with new song structures and Davis’ recording of, for instance, Dig, hinted at things to come. The mid-fifties tunes and albums of this influential threesome, especially Silver’s compositions The Preacher and Doodlin’ (From Horace Silver And The Jazz Messengers, February 6, 1955), Art Blakey’s Live At Bohemia-album (November 23, 1955), Miles Davis’ composition Walkin’ (April 29, 1954) and the trumpeter’s work with his first great quintet of 1956 (That quintet consisting of Davis, Coltrane, Garland, Chambers and Philly Joe Jones is considered a key figure in itself) are defining moments and pointed the way to a music that, even if it was indebted to bebop, broke out of the straightjacket of its song structures and uptempo rhythm in favor of a mid-tempo, minor-keyed and more urban kind of jazz.

Arguably, the invention of new musical paths (and creative paths in general) is not the outcome of a ‘lightbulb’ or ‘Eureka’ moment by one or another major inventor. It’s more a gelling of spirits, the result of simultaneous experiments by like-minded artists, in this respect also including Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Kenny Dorham, Sonny Clark, Cannonball Adderley et al. Hard bop wasn’t a clear-cut blueprint which everybody consciously decided to work with, it was more elusive, kind of like a coloring picture that was continuously reshaped by the distinctive colors of the modern jazz personalities. A few guys brought along the coloring picture, while the rest influenced these inventive few in the process and were essential for bringing about their visions.

Hardly a major stylistic innovator, instead Lou Donaldson is a hard bop frontrunner who colored the picture with the tastes of urban Afro-Americans while retaining the forward motion of bop. New Faces New Sounds, Donaldson’s cooperation with the burgeoning trumpet star Clifford Brown, isn’t a fully grown hard bop album yet. Even if customary breakneck speeds are largely absent, style-wise it’s bebop all the way. The group plays a faithful version of Bird’s Dewey Square and the standard You Go To My Head, is treated by Lou Donaldson the way Charlie Parker plays ballads. Lou Donaldson’s tone differs from Bird’s, it’s silky and has a slight, alluring vibrato. Donaldson’s way of phrasing possesses an attractive, sing-songy quality. A tad of charming nonchalance as well, while the inherent logic stays evident.

The years 1952-54 comprise a fascinating transitional period between bebop and hardbop. Blue Note not only introduced Lou Donaldson and Clifford Brown as ‘new faces’, the label also put a series of other players in the New Faces New Sounds-10-inch-package, such as Kenny Drew, Elmo Hope, Wynton Kelly and Gil Melle. Highly collectable jazz artifacts. New Faces New Sounds marked Clifford Brown’s recording debut, pre-dating an 11 June Prestige 10inch with Tadd Dameron (A Study In Dameronia), a J.J. Johnson date (The Eminent J.J. Johnson I & II, June 22, 1953) and his debut as a leader on August 28, New Star On The Horizon. Already very impressive, Brown was nevertheless yet to make his indelible, iconic mark with the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet in 1955.

Clifford Brown is a perfect match (if Donaldson was inspired by Charlie Parker, Brown’s indebtness to trumpeter Fats Navarro is evident) and delivers a top-notch tune, Brownie Speaks. He shines brightly on Carvin’ The Rock, which also boasts a driving Elmo Hope solo and articulate, probing and explosive drums by Philly Joe Jones.

Marc Myers, contemporary jazz ambassador without peer, conducted an enlightening interview with Lou Donaldson in 2010. I can understand that Myers enthusiastically calls Bellarosa ‘a hard bop anthem if ever there was any’, but which monicker should we then reserve for Horace Silver’s The Preacher, Miles Davis’ Walkin’, Bobby Timmons’ Moanin’ or Hank Mobley’s Funk ‘N’ Deep Freeze? Bellarosa, nevertheless, definitely stands out. The tricky theme is taken at a brisk, medium tempo and the tune swings effortlessly. Donaldson’s solo, excepting a customary (excellent) flurry of Parkerisms, holds back on the usual bop embellishments and instead opts for easygoing, slightly-after-the-beat swing. Donaldson’s tale, consisting of a relaxed start, evenly arranged phrases and a long note held in suspension on the bridge is as alluring as they come. Excepting Donaldson’s tone, which is more developed and characteristic in 1953, Bellarosa is reminiscent of Donaldson’s November 19, 1952 take of Horace Silver’s Sweet Juice, which included Silver and Blakey. Sweet Juice reveals the tentative, developing working methods of Silver, while Donaldson’s statements cautiously wheedle their way off the stage of bebop’s theatre.

There’s this tune organist Charles Earland wrote that was dedicated to his former bandleader, Lou-Lou, in 1970. (recorded on Rusty Bryant’s Soul Liberation) And a while ago, the popular Dutch jazz group Bruut! performed their boogaloo tune, Lou, on national tv. Just two examples showing that Lou Donaldson was and still is a hard bop personality with a capital P. Donaldson, just shy of 90 years old and rarely performing these days, himself has been vocal enough in this respect, having repeated his mantra time and again that jazz ain’t nothing without the blues. Sure ‘Nuff! Imagining Donaldson’s shrill, frivolous voice is enough to raise a broad smile on your face.