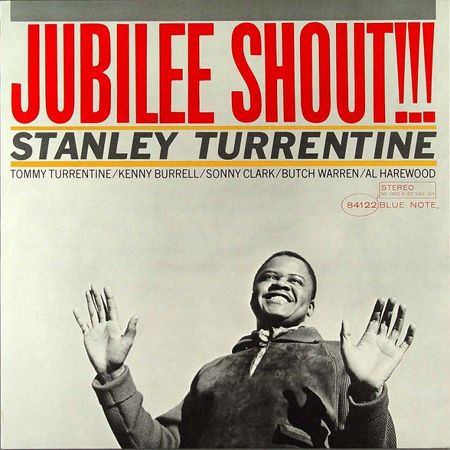

Don’t let the marketing gimmick of exclamation marks scare you off. Stanley Turrentine’s Jubilee Shout!!! delivers. It’s a lively, down-home session. Sonny Clark’s aboard. Yet, it was shelved and wasn’t released until 1986.

Personnel

Stanley Turrentine (tenor saxophone), Tommy Turrentine (trumpet), Kenny Burrell (guitar), Sonny Clark (piano), Butch Warren (bass), Al Harewood (drums)

Recorded

on October 18, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BST 84112 in 1986

Track listing

Side A:

Jubilee Shout

My Ship

You Said It

Side B:

Brother Tom

Cotton Walk

You Better Go Now (Little Girl Blue)

Stanley Turrentine. Mr. T. Fleshy, friendly face. A man you love to love. A Flophouse favorite. Adored by lovers of classic, smoky modern jazz. He’s got that thang. In 1962, the tenor saxophonist had hit his stride on the Blue Note label. Turrentine’s cooperation with pianist Les McCann, That’s Where It’s At, had been the last in a series of five albums that started in 1960 with Blue Hour, Turrentine’s association with The Three Sounds. His accessible, smart albums were good sellers.

Big, slightly breathy and warm-blooded, Turrentine’s tone renders a night out into town totally unnecessary. Save some money for a new vacuum cleaner. Stanley is party enough, blurs your head in drifting shreds of smoke, teleports the scent of soul food, the chatter of nocturnal Harlem nights right to the heart of your residence. Or flexible workspace. Or Club Med bungalow. He brings the blues. Not a hoarse kind, but stylized through the use of rich, resonant lines that are built from notes ending with a trademark, ever-so-slight vibrato and snappy bent note. Simultaneously, Turrentine displays modern jazz sensibility, but eschews excessive frills. A professor of tension and release.

Bonus: Sonny Clark! The maestro, three months short of his unfortunate passing, recorded erratically in 1962. But the dates he did were still top-notch: Jackie McLean’s Tippin’ The Scales, Grant Green’s posthumous Nigeria, Oleo and Born To Be Blue, and Dexter Gordon’s iconic A Swingin’ Affair. A couple of blues-drenched affairs: Don Wilkerson’s Preach Brother!, (just one exclamation mark!) Ike Quebec’s posthumous Easy Living. That’s it. Excluding Turrentine’s Jubilee Shout. Clark thinks out of the box, presenting hip blues voicings and eccentric asides in clusters of long, flowing lines that may not exactly stretch the boundaries of bars as frequently as in his heyday, but nevertheless comprise ample proof of a mind that still overflowed with ideas.

A bunch of top-rate guys to say the least, Stanley and Tommy Turrentine, Sonny Clark and Kenny Burrell have a lot of room to stretch out in a slow blues (Cotton Walk), uptempo cooker with a nifty line and stop-time rhythm (You Said It), lilting swingers (Brother Tom, My Ship) and a ballad (Little Girl Blue – wrongly credited on the vinyl release as You Better Go Now). The blast of the album is Jubilee Shout. A rousing gospel rhythm with pounding piano chords on the one and two sets the pace and is repeated between the 4/4 sections, which create room for the solo time of, subsequently, Stanley Turrentine, Tommy Turrentine, Sonny Clark and Kenny Burrell. It’s the musical equivalent of the archetypical lyric, ‘Sometimes I sing the blues, but I know I should be praying.’ Either way is right by me.

Why didn’t Blue Note release Jubilee Shout at the time? It’s a crackerjack session. Well, that was up to Alfred. The indomitable Lion also shelved, for instance, Lou Donaldson’s Lush Life, Lee Morgan’s Tom Cat, Wayne Shorter’s The Soothsayer and Grant Green’s Solid, which proved to be one of the guitarist’s crown achievements upon its release in 1979. However, Lion had many sessions to choose from in these instances and generally didn’t release more than three albums per artist per year. Market overflow wasn’t an obstacle in Turrentine’s case. That’s Where It’s At was the only album in 1962 to date. Maybe the title track and Cotton Walk were deemed too long. At any rate, the album was first released on a two-fer in 1978 and finally came out in 1986 with the originally intented cover art and catalogue number. CD release followed in 1988. It has also been included in the much-discussed, appreciated vinyl reissue series of Music Matters. The album was destined to bob up from the wealthy lake of Turrentine’s catalogue.