In 1966, the 19-year old, jazz-addicted drummer Eric Ineke sat watching Elvin Jones at the legendary Five Spot Cafe in New York City, awe-struck, stunned. A defining moment. “I realised what I wanted to do with my life. This was it! Period.”

Asizzling, hottest-day-of-the-year in The Hague, The Netherlands. A cooler spot in jazz drummer Eric Ineke’s garden, just around the corner from

where it was at at the original North Sea Jazz Festival, before it moved to nearby Rotterdam in 2006. Ineke’s bright, brown eyes behind glasses match

ton-sur-ton with freckled, brownish arms. A slender, good-natured and level-headed gentleman in a dark–blue LaCoste polo shirt, the 69-year old Ineke somewhat resembles a top-rate neurologist who’s expert in making the patient comfortable without routine gestures, alert and passionately involved in that mysterious, complex tissue called ‘brain’. And happy to share the obsession. Except that Ineke’s trade is the ‘soul’: jazz. “I had a job on a ship that brought back American students to the States. I provided backing for the musical entertainment, dixieland. We were supposed to travel further after our arrival in New York, to the West Coast, but a friend persuaded me to stay in New York. Took me to the Five Spot Cafe in the Bowery, which I knew from records. Like the Thelonious Monk albums on Riverside (

Misterioso,

Thelonious In Action,

FM) There a board said:

Elvin Jones, Monday nights. Wow! I was there, every Monday night, sipping a beer, right in front of Elvin in his grey suit, sweating profusively. He played with McCoy Tyner, Paul Chambers and Frank Foster. From 10 to 4. Understand? 10 to 4! I watched his every move. Elvin Jones had just left Coltrane. There he was, crammed behind that basic Gretsch kit, making a living from scratch in that rundown, bohemian bar. Talking about a jazz atmosphere! I can still see every detail, never will forget it. ”

“It was an awesome month. I also saw Kenny Dorham perform with Joe Henderson at Club Ruby, in a garden. They played with McCoy Tyner, Grachan Monchur III, Joe Chambers. There’s a Blue Note line-up for you! I went to see Hank Mobley with Blue Mitchell and Billy Higgins. Boy oh boy. And as a dessert, the Roland Kirk Quartet. Of course, I never imagined that I would play with these guys later on, with Hank Mobley, and Joe Henderson, and Frank Foster.”

They were just a few of the legends that Ineke would collaborate with in his adventurous, distinguished career. Eric Ineke was born in Haarlem, The Netherlands. At the time, the Dutch city that gave Manhattan’s famous jazz neighborhood Harlem its name, boasted a lively jazz scene. The young Ineke learned the basics from many experienced jazz musicians and built lasting friendships and collaborations with players like the tenor saxophonist Ferdinand Povel. Moving to The Hague, things really started rolling. “The Hague was the nr. 1 bebop city in The Netherlands. Still is, by the way. (Ineke has been teaching at the Royal Conservatory of The Hague for 26 years now, FM) Dutch bebop originated there and the town was brimming with excellent players, like Rob Agerbeek, Frans Elsen and Rob Madna. There were others I met in the early stages of my career and built lasting cooperations with, like Ruud Jacobs, a great bass player. I played in Amsterdam, of course, where I took lessons from drummer John Engels as a 15-year old kid and met pianist and life-long pal Rein de Graaff.”

How did Ineke develop into one of Europe’s to-go-to modern jazz drummers, a versatile, hard-swinging drummer who was nicknamed ‘The Ultimate Sideman’ by long-time associate and friend, the saxophonist and flautist David Liebman and who looks back on a career that encompassed gigs and recordings with a myriad of high-standard fellow Europeans and countless masters like Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Mobley, Dexter Gordon, Lucky Thompson and Jimmy Raney, Ineke’s favorite guitarist? A question of talent, at any rate. And: right place right time. At the end of the sixties, during the reign of rock music, countless American jazz musicians sought refuge in Europe. Naturally, they checked out the best rhythm sections, which, honestly, initially were scarce for American standards. Americans depended on the best supporting musicians, like Alex Riel, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, Han Bennink, John Engels. And Eric Ineke.

School days. But instead of the bell, the phone ringed. “I got a phonecall from Wim Johan Kuiper in 1968, an enthusiastic, small-time impresario. Pianist Pim Jacobs wanted me for a gig with Hank Mobley. Unfortunately, Hank overslept, you know what I mean… I played with Piet Noordijk that night, which was swell! However, I was given a second chance a week later. The Mambo Bar in Groningen, Rein (De Graaff) secured that gig. Guitarist Wim Overgaauw was there. He’d given me Workout to check out. Here, go study. Well, I did, thorougly! Figures, Mobley didn’t play one note of that album!” Ineke doubles up: “He played standards, On Green Dolphin Street, On A Rainy Day. He was really good and it was amazing to hear that laid-back, fluent style I knew from records up close, and participate in this event. Mobley was very kind, but an introverted, taciturn guy. During the break, he said, ‘yeah man, not everything is coming out yet, but it’s swinging.’ Ok! Wim Overgaauw told me a story later on. While we were playing, Mobley asked Overgaauw ‘who’s your favorite guitar player?’ Wim answered: ‘Grant Green.’ So, ten minutes go by, when suddenly Mobley turns around and says: ‘Mine too.’ Whoa!”

Here’s another one that should be included in a new edition of bassist Bill Crow’s insightful and extremely amusing book Jazz Anecdotes, section Eccentric Cats: Ineke once played with the Canadian bandleader and trumpeter Maynard Ferguson, who did small group gigs besides his singular big band affairs as well. “An enormously sweet, engaging man. Only thing was, he’d studied yoga in India. Suddenly, during rehearsals for a tv show, Ferguson is standing on his head. Just like that! Camera’s rolling. What the hell is this?! Played pretty good as a soloist, Maynard.”

For Ineke, the late sixties and early seventies were a playing ground, the period to develop a distinct personality. What exactly is the trigger behind the process that turns a content white middle-class boy into a dedicated follower and Dutch envelop-pusher of the real deal, black American jazz? “For one thing, I started tapping that swinging 4/4 beat at an early age. The music, which was on European radio regularly, appealed to me. I think it was just in me. Secondly, when I heard modern jazz, I just flipped. That was what I aspired to play, dig, feel. By modern jazz, I mean real jazz, which has to include blues and swing. If you take those ingredients away, you’re left with a cold, tasteless dish. It’s improv. Sure, jazz is improvisation. But it’s nothing without blues and swing. So what do many musicians do? They flee to the barren land of free jazz. That’s their hiding place. What a waste. Having said that, there’s no shortage of fine young players. Like, for instance, Gideon Tazelaar and Floriaan Wempe in Holland. Hard bop lives, but the scene is smaller. Even though there are a lot of stages for young musicians in The Hague, my generation had more opportunity to play, practically every town, big or small, had a club to make miles in. Some seedy, ‘jazzy’ ones as well, the kind where pigs were roasted above the bar and loose women danced on the billiard table. Lovely. At the same time, those joints programmed all-night bebop, amazing!”

Live At Birdland, including ‘Afro Blue’, Impulse 1964

Big Band Sounds, Riverside 1959

Live At The Blackhawk Vol. 4, Contemporary 1960

(From left, clockwise: John Coltrane – Live At Birdland, Impulse 1964; Philly Joe Jones – Big Band Sounds, Riverside 1959; Shelly Manne And His Men – Live At The Blackhawk Vol. 4, Contemporary 1960)

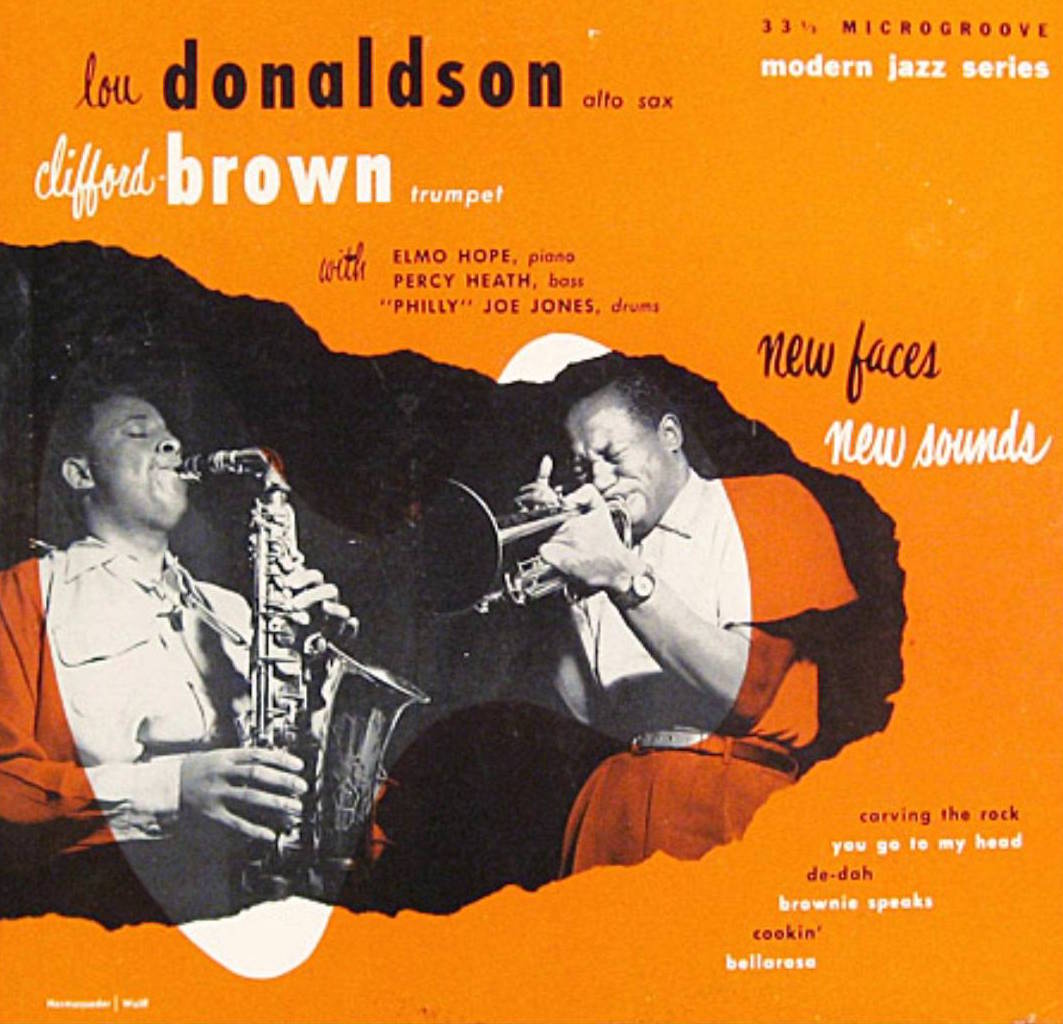

To my short assessment of Eric Ineke’s hard-swinging style of propulsive cross rhythms, which mixes weighted quarter notes with articulate, relentless snare and bass kicks, Ineke adds: “That is my personality, right there! Propulsive! I’ve got my influences, naturally. In short: Elvin & Philly. Both Elvin Jones’ loose triplet feel and Philly Joe Jones’ horn-like phrasing have always fascinated me tremendously. When I studied with Johnny Engels, he gave me Philly’s Big Band Sound. I heard the phrasing and thought, Eureka! I loved Roy Haynes and Max Roach, of course, but Max is more cerebral. Philly is dirty, sleazy, hip. Elvin too. How would I specify Elvin’s pulling and pushing? That’s all about time. You can make a measure as big as you want to. Elvin relished that kind of experiments. When I heard Elvin on Coltrane’s Live At Birdland, on Afro Blue, I totally freaked out.”

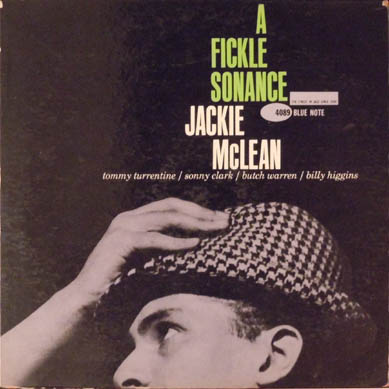

“Indeed, you might say I’m a descendant of the 2nd generation of modern jazz drummers. I love Billy Higgins, Louis Hayes, Mickey Roker. And Shelly Manne. You know those five Live At The Blackhawk albums? Oh boy, Manne swings like he’s got the hounddogs on his trail. It may be recorded on the West Coast, but it’s essential hard bop, including a fabulous Joe Gordon and supurb Richie Kamuca.”

(Left: Elvin Jones, right from top: Philly Joe Jones; Louis Hayes; Billy Higgins)

Listening to Eric Ineke talk so fervently about America’s sole original art form, one realises once more that its main characters sculpted so articulate and dedicated a statue from happenings that were, more often than not, basically very tragic and in surroundings that, in the USA, were uncomfortable and harsh. For musicians that deserved as least as much status as the revered classical composers, it’s an act that demands uncommon, relentless drive. Ineke gladly presents a host of legendary tenor saxophonists that exemplify that struggle and victory to the max. Eyes twinkle. Really, Joie de vivre is built in Ineke’s system like a microwave in a modern-day kitchen. “Where to start? Dexter?”

Please do.

“If there’s one guy who had a tendency to play behind the beat, it’s Dexter Gordon. Mobley, slightly, of course, but Dexter even more, especially when he hoisted those big glasses down his throat… Dexter, by the way, still played excellent when drunk. Amazing. I played with him over a period of five years, from 1972 till 1977. All Souls is a recorded document of our cooperation. It was supposed to be with Rein, but he had to pass and Rob Agerbeek filled the piano chair. What do you do with such a laid-back Gordon? Groove on, that’s the only way. Once you start following his beat, the whole building goes up in flames. A class act like that, his drag is the magic. Keep rollin’ is my advice, it creates a certain tension, which makes it special.”

“Pescara 1973 was great. That’s a major festival, all the big guys were there, still are. Miles was there, Horace Silver. It was in the contract that our Rein de Graaff Trio would act as the basis for the night’s jam session after our gig with Dexter Gordon. Everybody was at the jam session. All members from Miles’ outfit. They were fed up with rock and wanted to play bebop. We did. Dave Liebman, Al Foster, and finally Dexter Gordon, sat in. It was a ball.”

“The last time I saw Dexter Gordon was in 1983. Dexter had returned to the US but occasionally played in Europe. He was walking through that long hall behind the bar of the Jan Steen Zaal in The Hague. I shouted: ‘Dexter!’. The long-tall legend turned around and said, in his deep, gritty voice: ‘Ineke! S.O.S. Same Old Shit.’. Haha! What a character! It was kind of a darkly humorous crack though. At that stage in his life, Dexter was tired.”

Alternating between performances with Al Cohn, Teddy Edwards or Clifford Jordan must have required some adjustments from Ineke. “Certainly time-wise. Joe Henderson, for instance, had a kind of floating time, free. And he was so advanced, harmonically, rhythmically. But somehow I fit in with his style very well. I played with Joe a couple of times over the years. One gig was in Amsterdam’s Hotel Krasnapolsky. Henderson was in Europe, had a couple of days off and just wanted to play. So, they called me and Frans Elsen, Henk Haverhoek. We played Recorda Me, ‘Round Midnight and Joe was on fire. Not more than 10 customers, every one of them a jazz musician!”

The fastest gun in the East. Johnny Griffin, ‘The Little Giant’. Flurries of Parker and big shots of rhythm and blues. “That was an exam at first. Griffin wanted me to play like Art Taylor, ‘bombing’ the bass drum. Mean what you play, that is what I learned, literally. Tough, but a party! Griffin, for instance, counted off Wee. Breakneck speed. Marathon choruses. Then, suddenly, Griffin signs off, ‘I got it, I got it, I got it!’. A cappella flights. After that, it’s Rein’s turn. Griffin is relaxed, standing beside Rein, clapping hands, ‘blow baby, blow’, and laughing. Time for trading fours and eights… then it’s my solo turn… Man, near the end of that I’m about done. But no, Griffin shouts, ‘go on, go on…’ I do, although my body threatens to implode through the process of spontaneous combustion. And then, in comes Griffin: BAM. Climax. People go crazy, pandemonium.”

“Talent and right place, right time, I guess so. But here’s the essence, right there: dedication. And a competitive spirit. Going from the word ‘go’, flying from the first note… I’ve experienced it with Dizzy, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Phil Woods, George Coleman, and contemporaries Pete Christlieb and Eric Alexander. They just take you away with their beat, from note one. Frank Foster? We played Billie’s Bounce. 20 choruses, Foster builds a solo going from the style of Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young to those harmonics of Coltrane, major jazz history encompassed in one man, one solo. In hindsight, I understand. Go figure, when I toured with Frank, he wrote arrangements of Giant Steps in the back of the bus. Excellent arrangements. Besides, when I saw him at those eponymous performances with Elvin Jones at the Five Spot in 1966, I remember seeing him practising Coltrane’s ‘sheets of sound’ after his 10 to 4 gig, at about 4:30 in the morning. Obsessed, a workaholic. What a man. The tireless effort of these guys, it’s an American mentality. I very much took it to heart.”

“Luckily, there were other guys like me in my country.”

Like Eric Ineke, pianist Rein de Graaff was a self-taught jazz musician eager to make his mark in the modern jazz landscape. They have been cooperating for four decades now. Almost glued together like one, indivisible entity. “We stem from the same source. Even if we wouldn’t play together for five years, I’m dead certain that the vibe would be there from the first note.”

The list of American musicians that Ineke and De Graaff (including subsequent, long-time bassists Koos Serierse and Marius Beets) supported from the late sixties to the present, a great deal as part of the illustrious Stoomcursus Bebop and Vervolgcursus Bebop (performances and jazz history courses) that De Graaff organised in Holland, is remarkable. During the seventies and eighties, they also recorded prolifically with the Rein de Graaff/Dick Vennick Quintet, which ventured more and more into modal, McCoy Tyner-ish territories. While discussing Ineke’s period with tenorist Ben van den Dungen and trumpeter Jarmo Hoogendijk, Ineke says that the De Graaff/Vennik Quintet’s 1975 album Modal Soul was the reason that the young Dutch rising stars asked Ineke to fill in the drum chair of a quintet that also included another long-standing future Ineke-regular, the exquisite pianist Rob van Bavel. The rest is major Dutch jazz history. A dynamic, explosive hard bop quintet that was inspired by guys like McCoy Tyner, Woody Shaw, Joe Henderson, Elvin Jones and Joe Farrell, the Van den Dungen/Hoogendijk outfit was highly acclaimed in Europe in the early nineties. ‘Not only in Europe. Montreal in Canada was fantastic, a highlight. We played for an audience of three thousand people, they all went crazy. Hunted us for signatures. I had to sign my drumsticks. It was crazy, a pop star scene. Of course, Ben and Jarmo were sharp cats. Appreciative of the stereotypical groupie and the sneeze and swallow as well. It didn’t prevent them from playing at the top of their game. It was a blast.”

(Left to right: Frank Foster; Rein de Graaff, Henk Haverhoek, Eric Ineke & Dexter Gordon; Jarmo Hoogendijk & Ben van den Dungen)

Ineke ponders. Silence, if just for a moment. “Did you know that, in fact, it was Ferdinand Povel, Henk Elkenbout, Fred Pronk and me who introduced the revolutionary music of Coltrane in The Netherlands? We played Giant Steps live in 1967/68, the whole album! It’s not in the history books, but it should be. Well, it is now.”

2016, Ineke is just short of 70. For a decade now, Eric Ineke has been acting as the leader of a quintet for the first time in his life. Succesfully so, Eric Ineke’s JazzXpress has been recording and performing prolifically. Old skool hard bop, yet again, seems to have touched a nerve. Ineke, dryly, lovingly: “Lieb (Dave Liebman, FM) not only urged me to collect my memories and advice in a book – The Ultimate Sideman – he also brought up the idea of forming a group as a leader. Somehow, that man seems to be able to tickle my senses in a profound manner.”

Eric Ineke

One of the foremost European drummers, Eric Ineke (Haarlem, 1947) has performed and recorded with numerous legends such as Teddy Edwards, Ben Webster, Lucky Thompson, Clark Terry, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley, Freddie Hubbard, Barry Harris, Woody Shaw, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Pepper Adams, David “Fathead” Newman, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Al Cohn, Jimmy Raney, Dave Pike, Eddie Daniels and many others. From the late sixties till the present, Ineke’s career is marked by long-time associations with Ferdinand Povel, Rob Agerbeek, Frans Elsen, Rob Madna, Cees Slinger, Dick Vennik, Piet Noordijk, Charles Loos, Ben van den Dungen, Jarmo Hoogendijk, Wolfgang Brederode, Jesper Lundgaard, Benjamin Herman, Pete Christlieb, Scott Hamilton, Eric Alexander and Dave Liebman. For over 35 years, Ineke has been associated with the Rein de Graaff Trio. Ineke was a member of The Dutch Jazz Orchestra from 1984 to 2006 and has been leading his own hard bop quintet, Eric Ineke’s JazzXpress for ten years now.

Selected discography:

Rob Agerbeek Quintet, Homerun (Polydor 1971)

Dexter Gordon, All Souls (Dexterity 1972)

Rob Madna Trio, I Got It Bad (Omega 1976)

Rein de Graaff/Dick Vennik Quintet, Modal Soul (Universe 1977)

Jimmy Raney, Raney 81 (Criss Cross 1981)

Dave Pike & Charles McPherson, Blue Bird (Timeless 1988)

Ronnie Cuber/Nick Brignola, Baritone Explosion (Timeless 1994)

Slide Hampton meets Two Tenor Case, Callitwhachawana (Blue Jack Jazz 2002)

Eric Ineke’s JazzXpress, Cruisin’ (Daybreak/Challenge 2012)

Liebman/Ineke/Laghina/Pinheiro/Cavalli Quintet, Is Seeing Believing? (Daybreak/Challenge 2016)

The new album of Eric Ineke’s JazzXpress, Dexternity: The Music Of Dexter Gordon is coming out soon. Fried Bananas, the vinyl release of a 1972 Dexter Gordon performance with Eric Ineke and Rein de Graaff by Gearbox Records is due in November.

In his book The Ultimate Sideman (Pincio, 2012), Eric Ineke discusses and analyses his experiences with legendary musicians and contemporary colleagues. Essential reading.

Find out more about Eric Ineke on www.ericineke.com