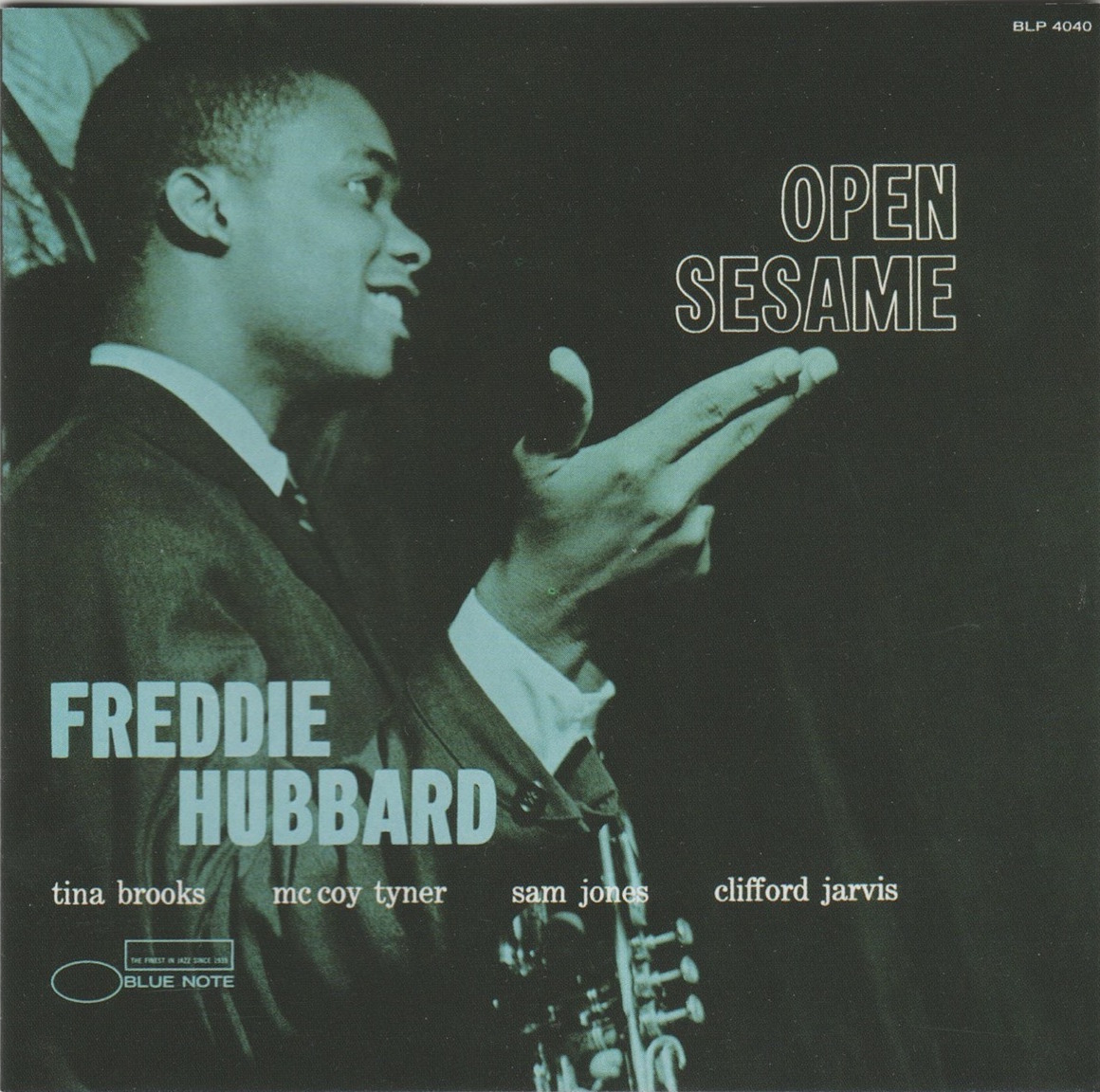

Freddie Hubbard’s celebrated debut as a leader on Blue Note, Open Sesame, is as much a Tina Brooks album than a Hubbard album.

Personnel

Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Tina Brooks (tenor saxophone), McCoy Tyner (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Clifford Jarvis (drums)

Recorded

on June 19, 1960 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 4040 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Open Sesame

But Beautiful

Gypsy Blue

Side B:

All Or Nothing At All

One Mint Julep

Hub’s Nub

Aweek later, Hubbard played on True Blue (read review here), the only album by Tina Brooks released during the undervalued tenorist’s lifetime. At the start of Hubbard’s career, Brooks proved to be a suitable springboard for the young trumpet player from Indianapolis. In later life, Hubbard lovingly commented on his mentor to Michael Cuscuna. “I loved Tina. He would write shit out on the spot and it would be beautiful. He wrote Gypsy Blue for me on the first record, and I loved it. I just loved it. Tina made my first record date wonderful. He wrote and played beautifully. What a soulful, inspiring cat.” (From: the liner notes of The Complete Blue Note Recordings Of Tina Brooks, Mosaic) Yet, Hubbard never used Brooks again for other sessions.

Gypsy Blue is a readily recognisable melody with a real gypsy jazz feeling and a cookin’ 4/4 section. Brooks wrote Open Sesame as well, a purebred hard bop tune. Great vehicles for Hubbard’s vital trumpet playing. At 22, Hubbard is buoyant and confident. On his debut, as modern jazz-minded Hubbard may be in the tradition of Clifford Brown and Fats Navarro, the newly arrived trumpet star, perhaps surprisingly, also brings to mind Louis Armstrong: the unabashed joy that speaks from his frivolous, virtuoso phrases, the exceptional range, the powerful notes that carry from one village to another, calling the children home. Imposing, and the audience hadn’t as yet seen a fully grown Hubbard. 1961’s Hub Cap, Ready For Freddie and Hub-Tones showcase a progressively mature Hubbard with adventurous choices of notes and more dark-hued phrasing. Surely, Hubbard’s pairing to many of Blue Note’s top-rate artists as well as Art Blakey in the fall of 1961 (Hubbard played with Blakey from 1961-64, appearing on, among others, Mosaic and Ugetsu) certainly have helped him find his own voice. So rapid was Hubbard’s evolution, that by late ’60 and early ’61 both Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane were happy to be assisted by the trumpeter on, respectively, Free Jazz and Ole Coltrane.

The fact that the immaculate Tina Brooks never reached the recognition that others off his day received, amazes to this day. Brooks certainly was tough competition for Hank Mobley, Junior Cook and Jimmy Heath. In any case, he’s an essential hard bop player. As the title track Open Sesame shows especially, Brooks threads unexpected paths where ordinary tenorists would opt for safe coda’s, either holding a long, gutsy note in suspension, or jumping to an off-centre triplet, meanwhile dropping meaningful pauzes in between. Brooks has a sinewy tone, a little rough around the edges for extra flavour and slighty drags behind the beat. His smokin’ stories brim with fresh ideas and slowly but surely pick up steam, sometimes by means of a churning out of notes deep from the inner parts of his fragile body, notes that traveled a long way and are just dying to jump out into the woods.

Open Sesame also features McCoy Tyner. The promising pianist had appeared on many recordings as a sideman, his debut as a leader on Impulse, Inception, followed in 1962. In 1961, Tyner completed John Coltrane’s eponymous group including Elvin Jones and Jimmy Garrison. Tyner’s comping brings a sense of urgency, his lines are lyrical and move rapidly in the upper register. Completing the line up are drummer Clifford Jarvis and bassist Sam Jones. Jarvis was 19 years old. Imagine how it must’ve felt to participate in one of those countless sessions at Rudy van Gelder’s magical Englewood Cliffs studio! Wet behind the ears, Jarvis nevertheless is unperturbed, swinging propulsively and providing resonant, well-placed accents. The 36-year old Sam Jones, one of the most sought-after bassists in possession of great walkin’ bass abilities and a definite down home bounce, was part of The Cannonball Adderley Quintet, with the landmark live album The Cannonball Adderley Quintet In San Francisco and his debut as a leader on Riverside, The Soul Society, under his belt. Freddie Hubbard couldn’t have asked for a better outfit to assist him in his rise to prominence as a new star on the trumpet.