Carlo de Wijs is crazy. Not as a bat but as the fanatic organist that is dying to take the beloved Hammond B3 to the next level. “It’s a movement I’m concerned with.”

The 56-year old Dutch organist, who recently has found a home in the center of Dordrecht in a neatly-furnished house with a studio in the cellar, is also crazy about Rhoda Scott, a pivotal personality in the development of his career. “I had been playing the electronic organ from age 7. But then my father, who was a parttime amateur musician, brought home an album from Rhoda Scott. Her sound immediately grabbed me by the throat. I thought,

this is what I want to do. From age 12, all I did was try to imitate the records of Rhoda, which were presented to me by my music teacher. I even went to Paris to buy a double album of hers! She is my first great love of the instrument. A beautiful woman too. I was madly in love with her! And you know what? Now she is a friend of mine. She kind of knew what I was up to with the Modular Hammond, did a little tour and came to the Codarts institute I’m associated with to do a workshop and talk with fans. Talkin’ she did. Rhoda is a very amiable lady of 79. We had long conversations night after night.”

De Wijs is a man with a plan, possessed with a distinct penchant for tickling the senses of the establishment, eager to seize opportunities and stretch limits. Certainly the musical challenges for the young De Wijs of the late 80s and early 90s, who apprenticed with accomplished Dutch mainstream jazz fellows like tenor saxophonist Harry Verbeke, bass player Hein van de Geyn and drummer John Engels, came from a rather surprising scene. “Hans Dulfer really was a gas. I had graduated from Conservatory with Swing Support, a funky jazz band with about three soccer teams on stage. That was a pretty grandiose affair, I was inexperienced and impulsive, but our subsequent tour worked out surprisingly well. (Swing Support is still the current name of the studio production company of De Wijs, FM) But Dulfer was something else. We formed a band with drummer Hans Eykenaar and guitarist Walter de Graaf. A jam band with hi-octane energy. We once did a marathon performance of 24 hours!”

“That is how I met his daughter, Candy Dulfer. She occasionally joined us on stage. She subsequently recruited me. Candy had just hit the big time. We traveled the globe like a major league act. That was really great. Then I started thinking that it wouldn’t last forever. Nothing lasts forever in the music business. So I started D’Wys, a monicker for my own soul and pop-jazz output. That was a really successful period, especially my cooperation with the ladies of Voices Of Soul. But instead of putting my Hammond playing at the service of a group identity, I wanted to have voices, harmony and concepts stimulating the development of my Hammond identity.”

Something was brewing in the back of his mind. The Hammond organ has been celebrating a resurgence once again. But the popular B3 series, brought to the fore by innovators like Jimmy Smith and Larry Young, fundamental to the reign of soul jazz in the sixties and, after a lull in the 70s and 80s, omnipresent in jazz and popular music, is an endangered species, much like the sable tooth tiger. It isn’t exactly clear how many were produced from 1955 till 1975 and how many are around today. And although De Wijs will find out one of these days – he has access to the original Hammond production administration in order to write his PhD on the Hammond organ – the number roughly resembles the amount of inhabitants of the Winesburg, Ohio that lies sleeping just below the brightly lighted big city you live in. Clones are superb, but digital imitations. So how can you update a vintage instrument for the 21st century? An intriguing question that De Wijs gladly grabs by the nuts. No, you won’t see the soft-spoken, slender organist chew on a cigar like the A-Team’s Hannibal and coolly state, ‘I love it when a plan comes together.’ He is pleased when something succeeds, rather jubilant, but instead of resting on his laurels, De Wijs is thinking of the next step. “Let’s just say that with everything I do, I’m presenting opportunities, offering solutions and ways to go.”

His PhD research for Codarts more or less points the way. “It’s called The Micro Dynamics Of Musical Innovation: history and the future of the Hammond organ. It’s about the stimulants of innovation and how to keep innovation going, centered around my core of interest, the Hammond organ. Now, Laurens Hammond was a brilliant fellow, an engineer and inventor who built a big company as a clockmaker in the thirties. But obviously, every innovator deals with the signs of the times. The signs of the times, regardless of the specific skills and special intellect of the innovator, are the actors of innovation. In this case, for instance, the Depression Era. Hammond was eager to find something else instead of the overflowing clock market and the government gladly granted Hammond’s application for a patent of the tone wheel organ, expecting many new jobs. Furthermore, new technical possibilities and ideas about marketing, the upbringing of Laurens Hammond, the role of his associate William Lahey and that of musicians of many creeds and fashions were fundamental stimulants of innovation.”

(Clockwise from left to right: Laurens Hammond; Rhoda Scott; Jimmy Smith)

“Does the thesis concretely include my beliefs regarding the future of the Hammond organ? Well, more of less. It’s scientific research about innovation, not a pamphlet. I have three more years to go! So I can’t reveal all of the content. But between the lines one may find suggestions as to how to update your product for the future. In this case, to stabilize and further develop the current positive Hammond climate. It may look as if Hammond is doing fine. Organ music is quite popular and the instrument is used in all genres. But the company definitely needs innovation in order to survive. When I introduced my ideas to Codarts, there was a lot of skepticism. Carlo’s that guy with a great hobby. Now I have supporters that acknowledge the merit of my research and the value of the concept and benchmarks.”

But De Wijs is not a professor. By his own account, a goodly professor gently led him through the desert of scientific research and thesis construction. De Wijs is a musician. And the demonstration of his philosophy on his Modular Hammond on the day of the interview is thoroughly instructive, if rather puzzling too. Seated on his bench, he looks less an organist than a pilot behind the dashboard of a Boeing 747. And he dashes from one knob to the other like he’s David Copperfield trying new tricks in his practice room. A staggering sight! Basically the Modular Hammond, developed with the help of, among others, Hammond technician Sjaak van Oosterhout, the ‘McGyver’ of De Wijs’s odyssee, is a hybrid of analogue and digital information. New technology is signaled through the unique tone wheel construction and routed back through the organ’s tube amplifier and Leslie speaker. The keyboards, keys and drawbars send MIDI data, separated from each other and thus creating a audio matrix that can be programmed at the operator’s will. The organ is connected with a modular synth, modifier system and computer software, which offers opportunities to sample, loop and manipulate sound while playing in real time. The system is underlined by separately amplified Moog bass technology in order to play independent bass lines.

It’s hard to believe that toying with his instrument once more or less started with implementing a Black & Decker drill in support of the organ’s transit system. Above the crunchy, creepy, sighing or booming sounds underscored by the funky runs or dense voicings he now plays off the cuff on his vintage and modified B3 in his studio, De Wijs will loudly say things like, ‘Listen, I’ve got the acoustic piano’s sustain pedal running through the Leslie speaker, that’s unique!’ or ‘Do you know of the Novacord? Hammond’s other invention built on tube amplification instead of tone wheels? We have programmed it in Ableton, which was really a bizarre experience for the guys of the Hammond company!’.

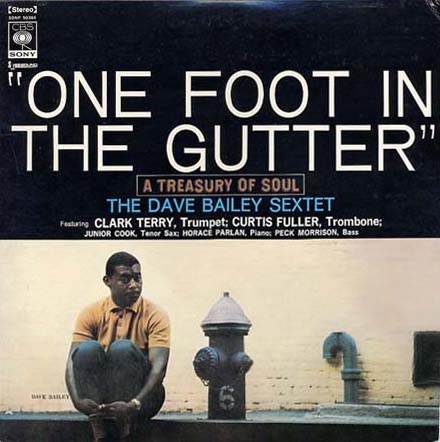

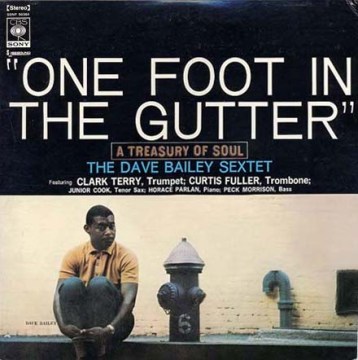

(Clockwise from left to right: Carlo de Wijs –

New Hammond Sound; Harry Verbeke/Carlo de Wijs Quartet –

Mo de Bo; D’Wys –

First Moves)

The goal of all this seeming wizardry is not tech for tech’s sake. “Absolutely not. It is a complex, continuing experimental process, but it’s still all about the music. This is a Hammond organ that has left the cradle of convention. A stepping stone. And inspiration, hopefully, for the younger generation of musicians, not only in jazz, but in pop, hiphop, electro. It is an invitation to make fresh choices of sound, a gadget paradise designed for creativity. At least I hope it works out that way. I’m also concerned with adding a third component: image. I’m very busy working this out with my buddy, drummer Jordi Geuens. We’ve made video clips with Job van Nuenen, where images correspond with the music and concept. We’re going to take it a step further in live performances, running images through the organ as well, in real time. This way the image will be the third band member.”

That’s much more than 74 miles away from mainstream jazz, the groove and grease of lore. Even from the clean contemporary non-smoking venues that present jazz, theatre or comedy for the loaded babyboom generation. “Yes, I’m pretty much of on a wild tangent, have been experimenting extremely for the last few years. Generally, I have been rather invisible for jazz fans. My concept is jazz-friendly but ready-made too, especially perhaps, for other genres and audiences. For me as an artist, this fact makes for a relatively hazardous transition from a stable fan base to a more eclectic and younger audience. I’m traveling new ground here, it’s quite scary! I imagine me and Jordi playing more fashionable venues, like electronic music festivals. Quite a liberating prospect. But at the same time, looks and sounds deceive. This music and concept hasn’t appeared out of the blue. They’re grounded not only in my special interest in the Hammond machine, but in my experience as an artist as well. Above all, I would say. I was immensily stimulated by my musical heroes.”

Perhaps like all inspired, serious journeymen, the young De Wijs wanted to become ‘the best organist of the world.’ A healthy yet romantic outlook that soon developed into the more level-headed aspiration to form a distinct personality under the wings of ‘the gods’. In the case of De Wijs: Jimmy Smith, Rhoda Scott, Joe Zawinul, Eddy Louiss, Quincy Jones and Prince, among others. “You’ll always hear Jimmy Smith in my playing, even during the wildest experiments. No matter how excellent his followers were, he’s the boss of mainstream organ jazz. At the other side of the spectrum, there’s keyboard player Joe Zawinul. He’s my greatest inspiration in the search of a New Hammond Sound. Zawinul dedicated his life to this kind of experiment in a more complex era, since the technology was more primitive. It was amazing how he found his own voice with all that equipment on stage. His son was a wizzkid and had to solder more than one connection between Rhodes, Arp, pedal or mixer. Lest we forget, it required the original vision and endless creativity of master musician Joe Zawinul to squeeze viable artistic statements from the gear. He’s a unique musician that defies imitation.”

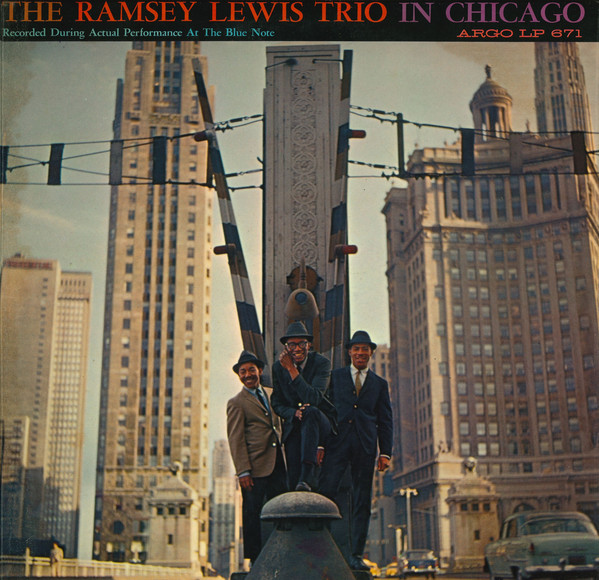

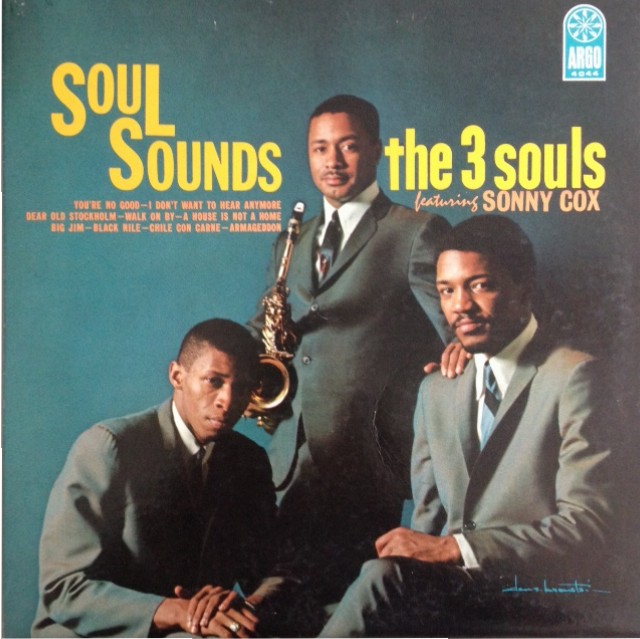

(Clockwise from left to right: Joe Zawinul; Stan Getz –

Dynasty; Rhoda Scott –

Take A Ladder)

Eddy Louiss is not the most obvious ‘hero’. “He is to me. Louiss also was an unconventional player who defied ready-made categorization. Born in Matinique, this Frenchman had a bit of Africa in him. He’s classically trained. His touch is amazing and he’s always looking for different colors. He made some excellent records with Kenny Clarke, the trio album with Clarke and guitarist Rene Thomas stands out. But the greatest records to me are the ones that stray away from orthodoxy. There’s one with Stan Getz that’s out of sight, Dynasty: Live At Ronny Scott’s. It reveals his sing-songy lines, unusual timing and sound.”

The unorthodox approach is what attracted De Wijs to Rhoda Scott as well. “Rhoda’s craft of execution, voicing, arranging is unmatched. Perhaps never more so than during her early career. She really developed a very personal style. Those early albums, like Take A Ladder, A ‘l Orgue Volume 2, Live At The Olympia, don’t have an exclusively straight-forward jazz conception. Her phrasing is a bit angular, but her orchestral approach is very striking. She really makes the organ sound ‘complete’. The sound is massive, voluptuous! That sound really turned me on.”

“Do I know of the Bennett Machine from organist Lou Bennett? Yes. Talkin’ about a pioneer. Bennett was a bass pedal virtuoso and his invention (Bennett added electronic special effects which allowed him to multiply the voices of his instrument and achieve a double bass sound as well, FM) was groundbreaking, if very unstable. It regularly broke down during performances. In general, his ideas weren’t picked up. Bennett wasn’t your best marketer, unlike Rhoda Scott. Interesting that you ask, cause, coincidentally, Rhoda is finishing her master thesis on the Hammond organ. Do you know what? Lou Bennett, who like Rhoda was based primarily in Europe, is a key figure throughout. Amazing, right! When I told her about and demonstrated my Modular Hammond, Rhoda gasped: ‘Oh, Lou would’ve been overjoyed! The things he was trying to work out with his raggedy construction, you are accomplishing here and now.’

Looks like Carlo de Wijs is slowly but surely becoming an actor of innovation himself.

Carlo de Wijs

Hammond organist, composer and producer Carlo de Wijs (56) recorded and performed with Harry Verbeke, John Engels, Candy Dulfer, Steve Lukather, Gary Brooker, Rhoda Scott, Red Holloway, Benjamin Herman and Jesse van Ruller. He has been leading several successful groups, notably D’Wys with Voices Of Soul. De Wijs was artistic manager of the pop and jazz department of Codarts in Rotterdam till 2014 and is the initiator of the Hammond bachelor and master.

Selected discography:

Harry Verbeke, Mo de Bo (Timeless 1985)

Swing Support, Avenue (Polygram 1990)

D’Wys, First Moves (Move 1999)

Trio Engels/Middelhof/De Wijs, Live At North Sea Jazz Festival (Munich 2001)

D’Wys, Turn Up The B! (Red Bullit 2002)

Benjamin Herman, Deal (Dox 2012)

Carlo de Wijs, New Hammond Sound (Rough Trade 2012)

Check out New Hammond Sound Project’s (Carlo de Wijs, Jordi Geuens, Job van Nuenen) brandnew clip Element Cm on YouTube here.

Go to the website of Carlo de Wijs here.