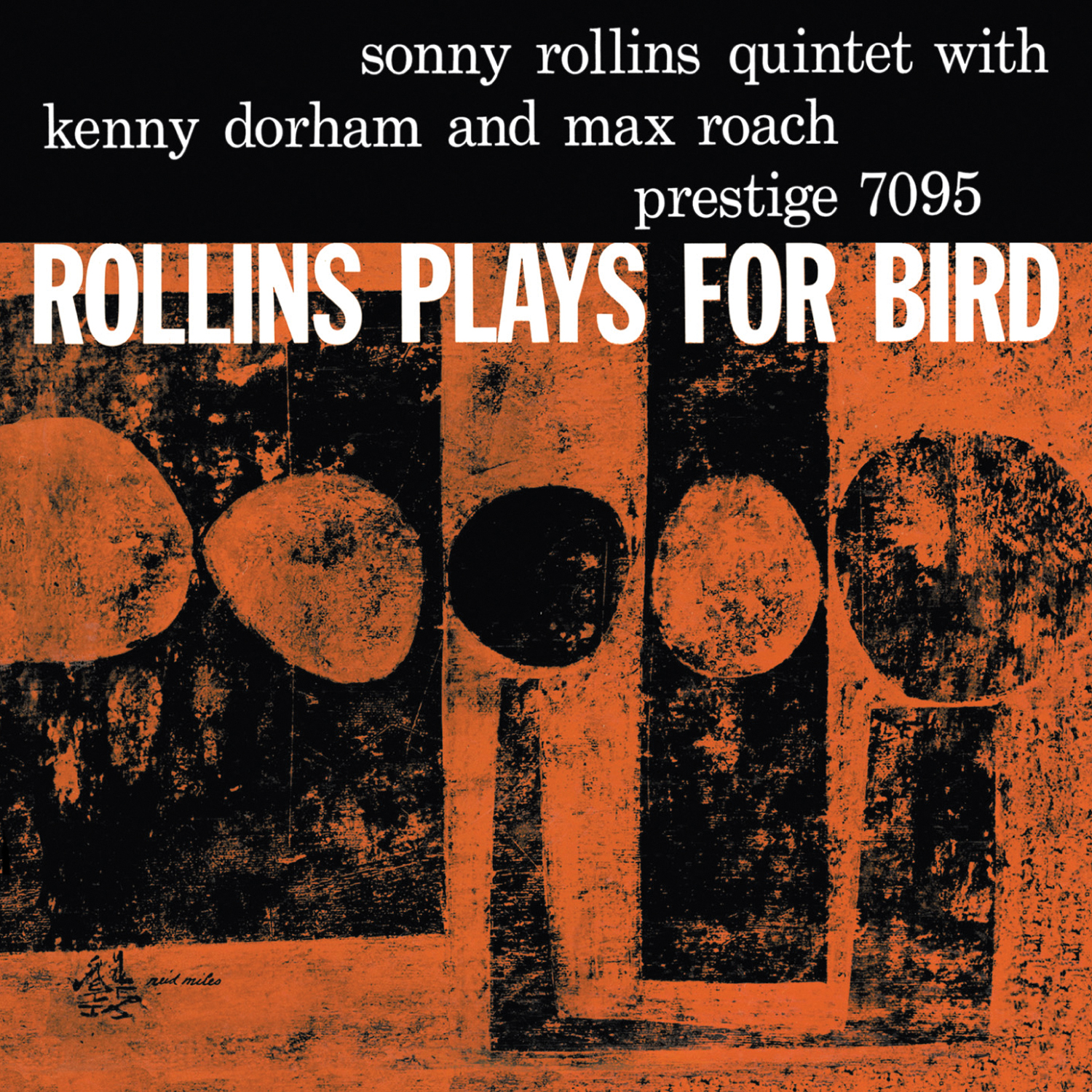

Sandwiched between the colossal Saxophone Colossus and future landmark albums Way Out West and A Night At The Village Vanguard, Rollins Plays For Bird is a mildly disappointing homage to Charlie Parker from, paraphrasing Gunther Schuller, the central figure of the erstwhile renewal of jazz.

Personnel

Sonny Rollins (tenor saxophone), Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Wade Legge (piano), George Morrow (bass), Max Roach (drums)

Recorded

on October 5, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as PRLP 5097 in 1957

Track listing

Side A:

Bird Medley: I Remember You / My Melancholy Baby / Old Folks / They Can’t Take That Away From Me / My Little Suede Shoes / Star Eyes

Side B:

Kids Know

I’ve Grown Accustomed To Her Face

It would be hard to top the Colossus, of course. One of the classic jazz albums of all time, it displays Rollins at an early peak, inventing new possibilities for jazz and the tenor saxophone: the exuberant and structurally logic improvisation of Blue Seven, the knack of turning unconvential material like Moritat into simultaneously complex and accessible gems, the introduction of exotic (West-Indian) roots and rhythm in the unforgettable calypso tune St. Thomas (A tune credited to Rollins, but actually a traditional that was first recorded by Randy Weston as Fire Down There in 1955) and the exploration of the tenor’s full range in ballads like You Don’t Know What Love Is.

Little of that on Rollins Plays For Bird, a recording of the Sonny Rollins Quintet, which was actually the line-up of The Max Roach Quintet shortly after the passing of trumpeter Clifford Brown and pianist Richard Powell. It feels rather as if Rollins is treading water and not getting to the point one would hope for in the case of a tribute to one of his major musical forebears, Charlie Parker. The Bird Medley that takes up the full 23 minutes of side A does possess a relaxed, swinging vibe and a tacky structure where Rollins, Dorham and pianist Wade Legge subsequently guide us through the themes. Dorham’s sweet-tart tone and fluent, unhurried phrasing are assets. The confident flow of Rollins’ lines is evident, the finest moments coming when he playfully explores the low register of the tenor sax in They Can’t Take That Away From Me.

However, considering Bird, the choice of repertoire hardly does justice to the modern music giant. Indeed, Parker regularly played these tunes but one would expect songs that he wrote himself or configurations of standards that have become iconic. Moreover, a medium tempo (excluding a short double-time section) is maintained throughout, interspersed with formulaic theme-solo-theme sections and trading of fours between drums and soloists. Attention easily drifts elsewhere. Compared with the commanding title track of Freedom Suite, the cooperation of Rollins with Max Roach and Oscar Pettiford of five months later, a medley of varied Rollins originals that also takes up the whole of side A, the Bird Medley comes up a decisive second. In favor of the latter, it consisted of one spontaneous take, while the Freedom Suite was glued together from seperate tracks.

I’ve Grown Accustomed To Your Face is a solid if not extraordinary ballad rendition, and a common choice of Rollins, who otherwise was revered for digging up obscure or unlikely standards. The Rollins original Kids Know, like the medley also played in medium tempo, has a frolic, catchy theme. Alas, Max Roach, seemingly not in the best of moods, practically drags it to death.

Just one week later, the clouds parted considerably and the quintet (including Ray Bryant) delivered the sprightly, inspired album Max Roach + 4. Six months later, Rollins delivered on the promise of Rollins Plays For Bird with the A Night At The Village Vanguard album, reviving standards and Parker contrafacts with a level of spontaneity and experimentation that has set a standard to this day.

Considering a giant like Rollins, expectations run, and ran, high. In this respect, Rollins Plays For Bird underachieves considerably.