Sonny Stitt suffered from the constant comparison with his friend Charlie Parker. Fact is, former manager of Ray Brown, Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven explains, that The Lone Wolf, contrary to common belief, already played bebop before he’d ever met Bird. A long-awaited debunking of myth.

You read about the nomads in North-Africa in history books. Or see them on tv on Discovery Channel. Weather-beaten people with leathery, wrinkled, red faces, dressed in full desert regalia, long robes from neck to feet, ingenuously arranged turbans on their heads. They’re wobbling on camels from dune to dune, finally reaching a tiny bit of half-fertile land, settling for a while, then moving on to the next challenge. Minding their own business. Until somebody takes them away as slaves. Or hires them as a tourist attraction below union scale.

The similarity with jazz legends is striking. You read about them in history books as well or, if you’re lucky, see them on public tv in a documentary, most likely on the European broadcasting systems. Somebody might give you a tip to go see the Miles Davis documentary on Netflix, featuring various fellow legends as supporting roles. This is the only way to know about them because, for various reasons, one being that America still hasn’t come to terms with the implications of an indigenous art form that simply by being itself defied white supremacy, the history of jazz is still largely absent from the curriculum of the educational system in the USA. (Let alone the history of serious rap and hip-hop, which was partly fueled by jazz and the most extreme – extremist – Afro-American outing in the history of American musical culture, essentially completely alien to WASP teachers, parents and kids and dealing with matters too scary to touch.)

In Hollywood, jazz is a tourist trap. To date, the jazz artist hasn’t been depicted on the big corporate screen in the manner he or she genuinely moves or behaves. Not even once. (Bird? Well… with all due respect: no) The latest effort was the jazz part of Babylon. Not quite. Unless professional jazz musicians are featured, e.g. Jerry Weldon and Joe Farnsworth in Motherless Brooklyn, these efforts are fruitless. (Not counting the indispensable European indie flick Round Midnight with Dexter Gordon)

So far, so bad. If poverty of portrayal is omnipresent, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that education falls short.

The jazz legends lived a truly nomadic life. Though they rarely if ever traveled with family. Jimmy Forrest worked on the riverboat in the band of the enigmatic Fate Marable. Up and down the Missouri and the Mississippi rivers time and again. Arnett Cobb journeyed with the so-called territory bands in the Mid-West, dust everywhere, in his nose, ears, crotch, brain. Duke Ellington worked around the clock, somewhere, somehow. He sat beneath Harry Carney in the car and traveled more miles on the American highways than Boeing 747’s fly over the oceans in their life span.

Charlie Parker, The Bird. Quite the wanderer in his all-too short and turbulent life. Sonny Stitt, The Lone Wolf. He liked to travel alone from East to West and North to South, picking up local rhythm sections and hard cash.

Speaking of Bird and The Lone Wolf. Whom crossed paths occasionally in their lives. Famously the first time, in 1942. Do you remember that story? Good one. Great jazz lore. Initially, it was chronicled by former promotor Bob Reisner in his book Bird: The Legend Of Charlie Parker in 1962. The story was quickly adopted by Ira Gitler for his liner notes of Stitt’s 1963 album Stitt Plays Bird. And repeated by critics and fans to this day.

However, Reisner and the herd forgot to mention or were ignorant of one thing. To be precise, nothing less than the punchline.

Early in his career, when he was 19 years old, Stitt played in the band of singer and pianist Tiny Bradshaw. Stitt had heard the records that Charlie Parker had done with Jay McShann and was anxious to meet him. Finally, one day, the band reached Kansas City, Bird’s place of birth. (see picture of Kansas City’s club-filled black district around Twelfth Street during the era of political boss Tom Pendergast below) Stitt: “I rushed to Eighteenth and Vine, and there, coming out of a drugstore, was a man carrying an alto, wearing a blue overcoat with six white buttons and dark glasses. I rushed over and said belligerently: ‘Are you Charlie Parker?’ He said he was and invited me right then and there to go and jam with him at a place called Chauncey Owenman’s. We played for an hour, till the owner came in, and then Bird signaled me with a little flurry of notes to cease so no words would ensue. He said: ‘You sure sound like me.’”

That’s it. That’s the official story. But it ends prematurely.

Because Stitt retorted: “No, yóu sound like me!”

“Yeah!” says Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven. “It’s amazing that none of the people in the business cared to tell the real story.”

(Stitt; Bird; Twelfth Street, Kansas City)

Swiss-born Jean-Michel Reisser was nicknamed “Beethoven” by the legendary Harry “Sweets” Edison. Son of a serious record collector that befriended jazz legends in the 1970’s, Jean-Michel sat on the lap of ‘uncle’ Count Basie as a three-year old kid. He eventually befriended Basie, Ray Brown, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Max Roach, Jimmy Woode, Milt Hinton, Sonny Stitt, Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Jones, Jimmy Rowles, Alvin Queen and various others. A savvy cat, he was hired as manager by Ray Brown. Besides managing Brown, Jean-Michel produced hundreds of records, tours and jazz documentaries. He has retired from the business now, lives in luscious Lausanne and, as passionate about his beloved art form as he’s ever been, is an enlightening jazz causeur.

“I would be stupid not to overwhelm all those legends with questions while they were still living and breathing. That way, I heard a lot of stories, directly from the source.”

Sonny Stitt, though, was rather reticent. “He was a great guy, but didn’t talk much. You had to take him by the arms and say, ‘hey motherfucker, I have some questions! He was the kind of guy that liked to drink and smoke and relax after a concert. It was only privately that Sonny ultimately got down to conversating about music.”

The punchline raises multiple issues. About the ignorance of the press. (Though Gitler, as we’ll see, spitballs something interesting at the issue.) About the mystery of parallel inventions in art. And, not least, about Stitt’s reputation and life. Much to his dismay, Stitt had to deal with comparisons with Charlie Parker all his life. Small wonder, since Stitt has always been a straight-ahead bop saxophonist, variating, apart from various commercial records, largely on the prevalent Tin Pan Alley changes and bebop’s contrafact compositions. However, a mere cursory afternoon of comparative listening between Stitt and Parker will reveal largely differing personalities to all listeners that trust their ears, whether beginners or aficionados.

Stitt’s a thoroughbred. Fine horse, plenty bulging muscle, shiny brown manes. Charging out of the gate, running powerfully but smoothly, eye on the finish line. Goal-oriented.

Bird’s a pinball at the mercy of a pinball wizard. It is eloquently maneuvered on the plate. Then, with a sudden push, it is smashed through the glass, careening around the arcade and miraculously jumping back into the machine.

No, yóu sound just like me!

Come again?

Reisser-Beethoven: “That’s the truth. It’s what Sonny told me when we talked about his meeting with Parker. Significantly, many people have told me about their interaction with Sonny. First of all, Ray Brown. Ray met Sonny in 1943. Ray said that he hadn’t heard about Parker until a bit later. He said, ‘I heard this young guy playing things I never heard before. Everybody says he’s playing like Bird, I said, no way. Sonny always had his own style’. Hank Jones played with Stitt in 1943 and he told me the same story. J.J. Johnson as well. He said he’d never heard about Bird until 1944, but he’d already played with Sonny Stitt: “This motherfucker had his style. He didn’t play like Parker. He played in the same vein, but it was different.’ Stan Levey told me a similar story.”

Vein is the word here.

Reisser-Beethoven continues: “This is the way of the arts. You sometimes see it happening in painting, that two great painters arrive at a similar concept. It works this way in music as well. For instance, the late Benny Golson explained to me that he composed a lot of tunes that he thought were pure originals but found out by listening to the radio that others had reached the same conclusion, without ever hearing Benny’s drafts. As far as the story about Stitt and Parker goes, Parker hadn’t totally arrived at his original style when he played with Jay McShann. It was only in 1944 when he had fully developed bebop harmonics. Stitt arrived on the scene a bit later and in the public eye and everybody said that he played like Parker. But historically, this is not the case.”

It is the way of the arts but also extends to other areas. Politics and social history, for instance, with strings of misunderstanding attached. Take Martin Luther King’s iconic I Have A Dream speech. Contrary to general belief, King didn’t invent the groundbreaking oneliner. He’d heard Prathia Hall, daughter of Reverend Hall, utter those words in a remembrance service in church after an assassination on black citizens. King used the sentence in subsequent speeches but it didn’t catch on until he so imposingly integrated it in his speech at the march to Washington, urged by singer Mahalia Jackson.

Back to our musical icons. Paradoxically, Reisner and Gitler mention an occurrence that backs up the idea that giants like Parker and Stitt arrived at the same musical conclusions apart from each other. (In this respect, it should also be noted that drummer Kenny Clarke worked on new rhythms in the very early 1940’s, a glimpse of the congruency of ideas of Parker, Gillespie, Clarke, Roach, Monk, Pettiford, Mingus, Powell in the mid-1940’s) Reportedly, Miles Davis saw Stitt coming through St. Louis (Davis’s birthplace) in 1942 with Tiny Bradshaw’s band, ‘sounding much like he does today as far as general style is concerned’. Gitler says: ‘We don’t know whether this was before or after the Kansas City confrontation, but Stitt has long insisted that he was playing this way before he heard Parker.’

Chockfull of lore, Gitler’s liner notes of Stitt Plays Bird (by the way, a record with some stellar solos by Stitt, regardless of the underwhelming band spirit) also mentions something that Charlie Parker supposedly said to Stitt a little while before his death in 1955: ‘Man, I’m not long for this life. You carry on. I’m leaving you the key to the kingdom.’

Epic. Lord Of The Rings-style. However, nobody in his right mind believes Bird to be capable of uttering such pompous near-last words. ‘Please pass that piece of lobster,’ seems more likely. Or, in a more serious friend-to-friend/father-to-son vein, ‘I urge you not to do as I did, stay away from the needle’.

In fact, Bird did say something of the sort to young disciples, that didn’t listen and with few exceptions got hooked. Nothing of the sort was advised to Sonny Stitt, though, who lived with his own demons and did time in Lexington, Kentucky in 1947/48. Precisely at the time that bebop gained nation-wide traction. Bad luck. Reisser-Beethoven: “I’m sure that his being out of the public eye was a setback, but his main problem was criticism. He suffered from big depressions throughout his career. Everybody presented him as a clone of Charlie Parker. It was problematic. He wanted to quit many times. Eventually, he alternated with tenor saxophone. Dizzy Gillespie came up with this idea in 1946, when Sonny was in Dizzy’s band. Suddenly nobody said anything about Bird! Although he played the same lines, chords, improvisations. Dizzy said to me that, when Parker didn’t show up, he’d either call Lucky Thompson or Sonny Stitt. He loved Sonny Stitt.”

“In his view, Norman Granz saved his career. Granz took him out on the Jazz At The Philharmonic tours. He recorded him with Dizzy, Sonny Rollins and produced all those Verve albums. Sonny considered his Verve albums as the highlight of his career; notably Sits In With The Oscar Peterson Trio, New York Jazz, Plays Arrangements From The Pen Of Quincy Jones. He also believed his albums in the early 1970’s with Barry Harris, Tune Up, Constellation and 12! to be among his best.”

And so, the nomads traveled from East to West, North to South, dark-skinned birds and lone wolfs roaming from one asphalt jungle another, sometimes jubilant, rejoicing notes brimming with blues and Debussy, as excited as kids on a funny farm, sometimes shivering, hiding in a torn raincoat, at the end of the rope and the track. Charlie Parker and Sonny Stitt crossed paths more than once. Reisser-Beethoven: “Allegedly, they met several times. As far as I’ve heard, they were good friends. Charlie Parker didn’t say anything bad about Sonny’s style, no way. Dizzy said that sooner or later the critics were bound to put walls between them. It’s not only like that in music. But also in politics, religion, history. All too often, one guy tells the so-called definitive story and the rest follows it blindly. It’s a pity.”

Sonny Stitt

Here’s Stitt Plays Bird: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0I2Lcnn_hLs

Here’s I Remember Bird: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMEpRUTE_no&list=OLAK5uy_nuKI1RZPqZVIsRMGYW7kGI9RNO1uuxoRs&index=2

Very Vari!

FRIDAY NIGHT AT THE FLOPHOUSE –

There are worse things in life than hanging out with Sonny Stitt, Lou Donaldson, Eddie Harris and Rusty Bryant. All of them, with Stitt at the helm, played the electric Varitone saxophone and the Gibson Maestro Attachment in the late ‘60s, as a means to spice up their groove and experiment with sound.

Selmer introduced the Varitone extension on July 10, 1966 on a convention in Chicago. The Varitone is a control box for the attachment that fits on the bell of the saxophone, which is connected to a large amplifier. The player is enabled to achieve volume control, tone variations (allegedly 60 different sounds) and echo and tremelo effects. The octave effect – by pushing buttons the saxophonist can add a note an octave lower or silence the top note – is attractive, creating ways to experiment with timbre.

Stitt was fast. Merely two days after the convention, The Lone Wolf recorded his first album on Roulette with the use of the Varitone extension, What’s New!!!. Macabre ballad, lovely pun. Stitt used a killer band including trombonist J.J. Johnson and tenor saxophonist Illinois Jacquet (who himself gave the Varitone a go on two rare occasions on the album) and the rhythm section of guitarist Les Spann, pianist Ellis Larkin, bassist George Duvivier and drummer Walter Perkins, who are present as well on follow-up I Keep Comin’ Back. Parallel-A-Stitt was a small ensemble session featuring organist Don Patterson.

In the Downbeat issue of October 6, 1966, Stitt says, “It’s a revelation. It enables you to probe and find. It projects your own tone – not a distorted tone. Your individual sound doesn’t change. The mind will never get lazy with that help. You’re thinking all the time what to do next. All this gives you is something more to work with. It doesn’t help you to think better. It sounds so pretty. I love it. It’s the most beautiful thing that’s happened to me.”

“Big bands, organs, electric guitars, loud drummers can be quite frustrating to a person who’s trying to think while playing. With this new saxophone, a fellow can hear himself above anybody. He can play in a big ballpark and still be heard.”

Indeed, Stitt’s style remains the same, and while his Varitone records are not essential Stitt, he plays fluently supported by killer line-ups while toying with octaves and different sounds, prominently a hard and hootin’ sound which features a slight distorted edge that, despite his comments, I do hear. Nothing wrong with that. Anyway, unfortunately you won’t find anything of these three records on YouTube except the balladeering of What’s New. While checkin’ tunes after my vinyl listening session, I did come across a live performance of “electrified” Stitt with one of his greatest regular groups of Don Patterson and Billy James, playing The Shadow Of Your Smile at the Left Bank in Baltimore. Nice!

By 1970, likely Stitt’s contract with Selmer had run out. On Turn It On!, Stitt uses the Gibson Maestro Attachment. Hear him blast away on the title track with Virgil Jones, Melvin Sparks and Idris Muhammad.

Eddie Harris wanted his penny’s worth. The saxophonist played the Chicago Maestro Attachment on Plug It In! and Silver Cycles. Harris added the Echoplex, which could provide multiple tape loops which played back the recorded sound at constant intervals. It was therefore possible to play new melodies over the basic motif. Harris used the attachments to the benefit of his hodgepodge of soul and avant-leaning jazz of that period, like Lovely Is Today, Free At Last and

Coltrane’s View. Anything goes with Eddie, lots of grease and lots of feverish vibes and arguably the most interesting electrified player of this bunch.

Lou Donaldson quickly latched on to the Varitone. He played it on some of his popular jazz funk records with organists Charles Earland and Lonnie Smith and drummer Idris Muhammad. Donaldson used it sparingly, focusing on his tone, all silk and velvet and satin. Listen to Turtle Walk from Hot Dog and Everything I Play Gonna Be Funky from Everything I Play Is Funky.

On his only association with the Varitone attachment, Rusty Bryant pulled out all the stops on Night Train Now!, 1969 jazz funk affair with Jimmy Carter on organ, Boogaloo Joe Jones on guitar, Eddie Mathias on bass and Bernard Purdie on drums. Heavy artillery. Buzzing like a bee, howling like a bear, Bryant hits Cootie Boogaloo and John Patton’s Funky Mama right out of the ballpark.

Why did Stitt or the others did not extend their experiments with the Varitone and CMA in the ‘70s and beyond? Perhaps they eventually preferred the authenticity of acoustic sound over the ‘clumsy’ Varitone. Or maybe they felt constrained by the endorsements of the devices. I coincidentally heard just yesterday from my jazz friend Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven, who was friendly with Sonny Stitt, that Stitt hated the Varitone, which contrasts with his enthusiastic Downbeat comments.

Why did fusion artists did not pick up on the electric attachments? Most likely, before anyone cared to try, synthesizers provided all the sounds one could wish for. Or am I missing something?

Possibly. Immersed in the heavy sounds of these hot cats.

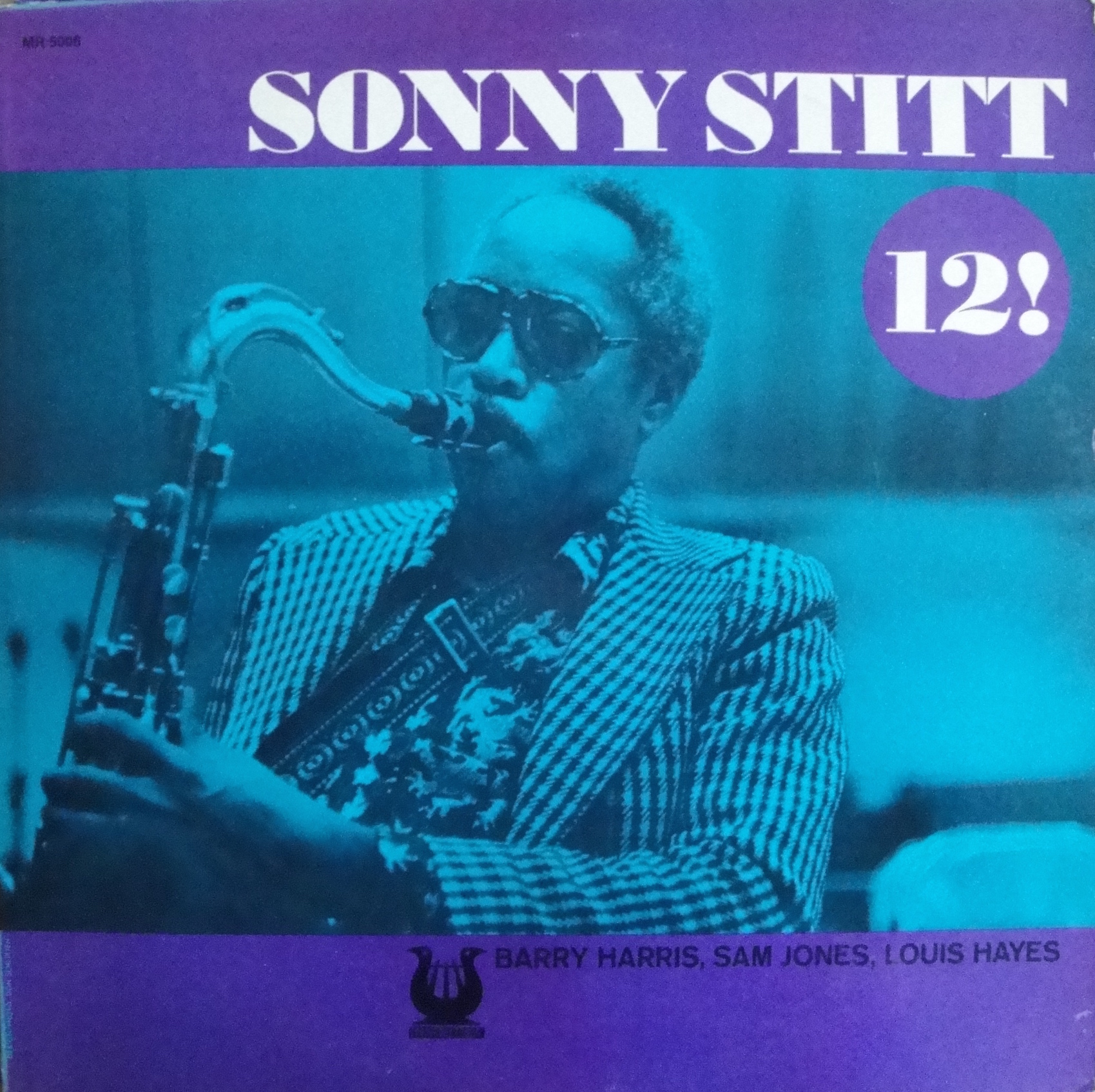

Sonny Stitt 12! (Muse 1972)

Nowadays, to define jazz is a Gargantuan task. It could mean such a hell of a lot. (and therefore, arguably, a lot of the time nothing at all) Nowadays, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis have become figures of mythic proportions. But in 1972, when Sonny Stitt’s 12! was recorded, jazz was at a low ebb after two decades wherein it had been a face with two odd sides. On the one hand, jazz – de facto still an affair of the in-crowd, had experienced a relatively meagre amount of attention in the US and Europe (certainly as compared to other, more traditional art forms) On the other hand, jazz did certainly not suffer from a shortage of clubs and record labels, and therefore a steady supply of work for musicians, however marked by hardship those conditions might’ve been. Speaking of 1972, those ‘relative’ days of wine and roses were over. And Sonny Stitt, who’d been there all the way and one of the great American jazz men who defined the era, still wasn’t a household name. Probably because he didn’t generate copy because of o.d’ing in a back alley or having hanged himself on the nearest shower rod.

Personnel

Sonny Stitt (tenor saxophone, alto saxophone), Barry Harris (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

Recorded

on December 12, 1972 in NYC

Released

as MR 5006 in 1972

Track listing

Side A:

12!

I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good)

I Never Knew

Our Delight

Side B:

The Night Has A Thousand Eyes

Blues At The Tempo

Every Tub

Instead Sonny Stitt kept on playing, prolifically, relentlessly. In fact, 12! finds Stitt – 48 years old – in true form, fresh and energetic. Stitt may have been out of sight for a while and may have made a mediocre album here and there in the sixties, yet had a great run of recordings in the early seventies, delivering the outstanding works Tune Up, Constellation and 12!. People again had to pay attention.

The opener and title track immediately makes clear where Stitt’s been at. In a twelve-bar blues (hence the title) the experienced rhythm tandem of Louis Hayes and Sam Jones vigorously crank out the chord scheme and Stitt alternates between outrageously fast and cleanly executed bop runs and tasteful and shouting blues statements. He’s on alto saxophone here and is heard quoting See See Rider, a gesture pianist Barry Harris picks up on in his turn, playfully making a reference to the same classic blues song at the start of his well-balanced solo.

I Got It Bad, virtually synonymous to Johnny Hodges, is a fine ballad. The rest of 12! consists of another dose of blues and bebop. A highlight is I Never Knew; it starts with a jumpy vamp and thereafter, up-tempo and in 4/4 time, Stitt wraps up the story he’s been telling ever since battling with Gene Ammons in the forties. Barry Harris solidly flies through the changes. Harris’ declaration of independence has long since been sealed, yet, at the same time, on this tune and album, Harris throws in more than a bit of Bud Powell.

That should be enough to satisfy the customer, but there’s more where that came from. In the ultra-fast Every Tub, a piece that suggests that in bop there was injected more than a dose of jump ‘n’ jive, Stitt is stimulated to the core by the red hot rhythm section and launches into a high-voltage solo that remains interesting because of Stitt’s unlimited imagination. Stitt pulls out all the stops, ending a three minute immaculate bop course on a wailing note. He’s mean. This is the Sonny Stitt young lions were hesitant to stand shoulder to shoulder with on stage, the Sonny Stitt that on those occasions seemed to deliver the delirious, yet despite its madness utterly coherent message: Here comes Sonny!

On 12! Stitt is assisted by an almost equally experienced set of cats. Sam Jones played with about all of them; and one of his solo albums on Riverside being named Down Home gives you an idea of the bassist’s intentions. Jones and drummer Louis Hayes have been one of the most prominent and exciting rhythm sections in Cannonball Adderley’s Quintet from 1959 to 1964. (Jones played on more recordings of the quintet, notably on the classic Something Else) Barry Harris was a sought-after pianist and is well-known for contributing his soulful, robust style to Lee Morgan’s famous hit record The Sidewinder.

Sonny Stitt’s style pretty much stayed the same over the years, he wasn’t the ‘searching’-type. Stitt is what he is, an authority, an institution. In the fifties and sixties many set Stitt aside as a mere copyist and disciple of Charlie Parker, which was ridiculous. Of course, undeniably, more than in others, in Stitt one could easily hear Parker, sometimes as much as one could hear Parker in Parker. That is, on a superficial level. Stitt learned from that bunch of brilliant innovators that created the new music labeled ‘bebop’, which permeated jazz for years to come, and he played his part in it as well – influencing the likes of John Coltrane along the way. What Stitt was doing in the sixties and seventies was keeping the flame of bebop alive and in the process attributing to the sense that it still was alive, not only in Stitt, but also in the minds and works of the younger generation.

This is what Stitt was doing, year after year, mostly in classic quartet or quintet settings but other settings as well, authoritatively, occasionally a bit half-heartedly, but more often than not by blowing everybody’s brains out. In the manner that is immortalized, for instance, in the grooves of 12!.

You may or may not know all this or you may or may not have heard something along these lines before. It wouldn’t be surprising, since a batch of renowned critics such as Dan Morgenstern have been more than eager to praise or defend Stitt. I take it for granted because Sonny Stitt deserves it that the tale of his frequently unrecognised importance to the jazz heritage keeps being told; that the records are being kept straight.

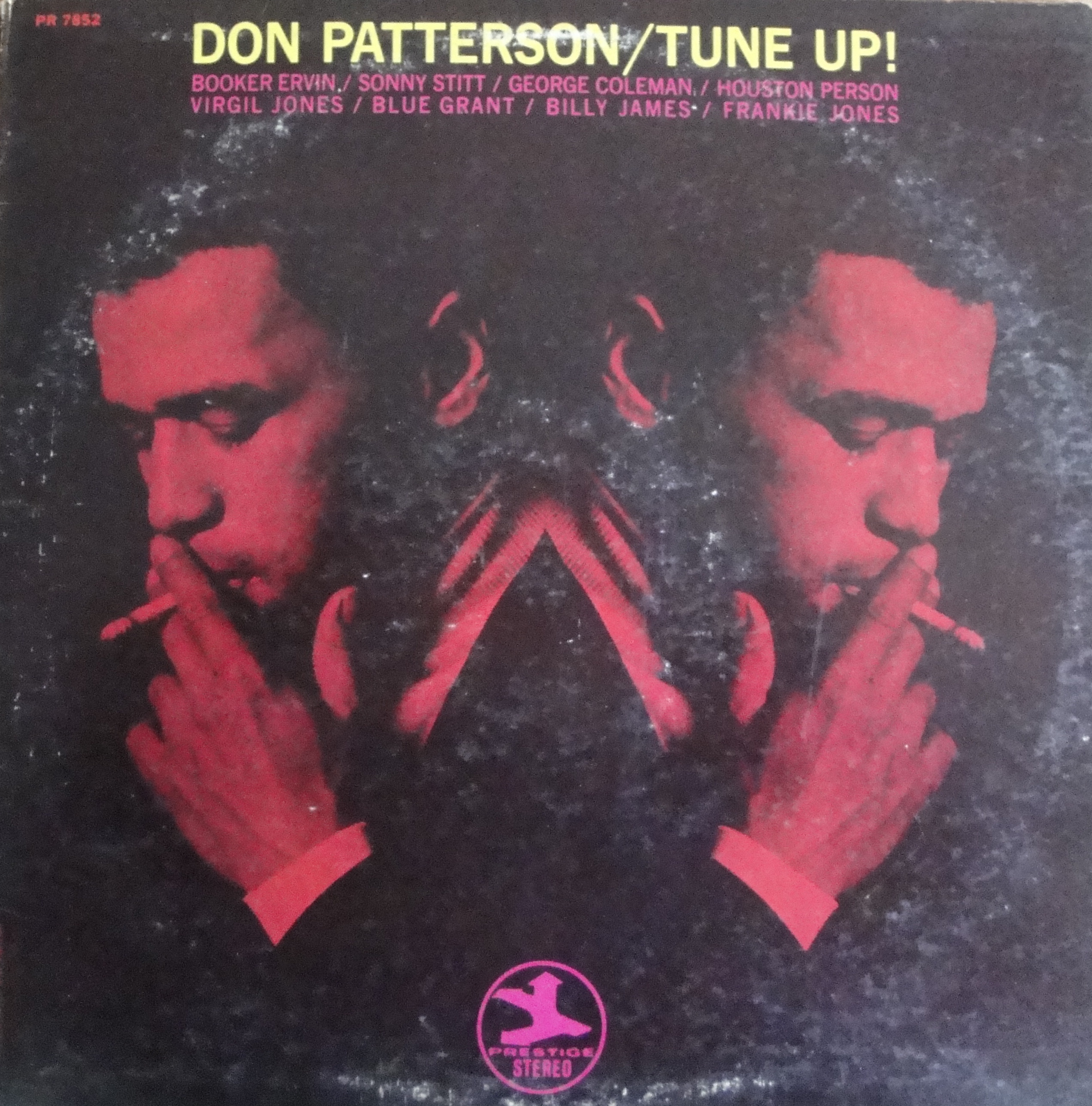

Don Patterson Tune Up! (Prestige 1964/1969)

Tune Up! is one more example of a record company’s policy to keep an interest in the career of a musician when he or she is absent with no apparent return ticket attached; in this case Don Patterson, whose hard road of drug abuse at the end of the sixties had become strewn thick with heavy rocks and barbed wire.

Personnel

Don Patterson (organ), Booker Ervin (tenor saxophone A1-2), Sonny Stitt (tenor saxophone A2, B1), Houston Personn (tenor saxophone B2), George Coleman (tenor saxophone B2), Virgil Jones (trumpet B2), Grant Green (guitar B1), Billy James (drums A1-2, B1), Frankie Jones (B2)

Recorded

Recorded on July 10 & August 25, 1964 and June 2 & September 15, 1969 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7852 in 1969

Track listing

Side A:

Just Friends

Flying Home

Side B:

Tune Up

Blues For Mom

It didn’t affect his playing on the title track, this album’s most interesting cut, a leftover from a September ’69 session that spawned two high-standard releases – Brothers 4 and Donnybrook. It would be hard to follow up Grant Green’s amazing solo on Miles Davis’ fast-paced composition – Green (credited as Blue Grant) showing no loss of remarkable straight jazz skills during his burgeoning funk jazz period – were it not that Don Patterson rises to the occasion, not tempted to flex his muscles in bragadocious manner, but instead stringing one dynamic, coolly delivered bop run to another, like multiple toy beads.

It’s difficult to make head or tail out of an album that presents four tunes from four different sessions, ranging from ‘64 to ’69. This nevertheless belies the good quality of these sessions, what with the standing of Patterson and sidemen such as Stitt, Ervin, Coleman and Jones, who confidently blow their way through standards and blues.

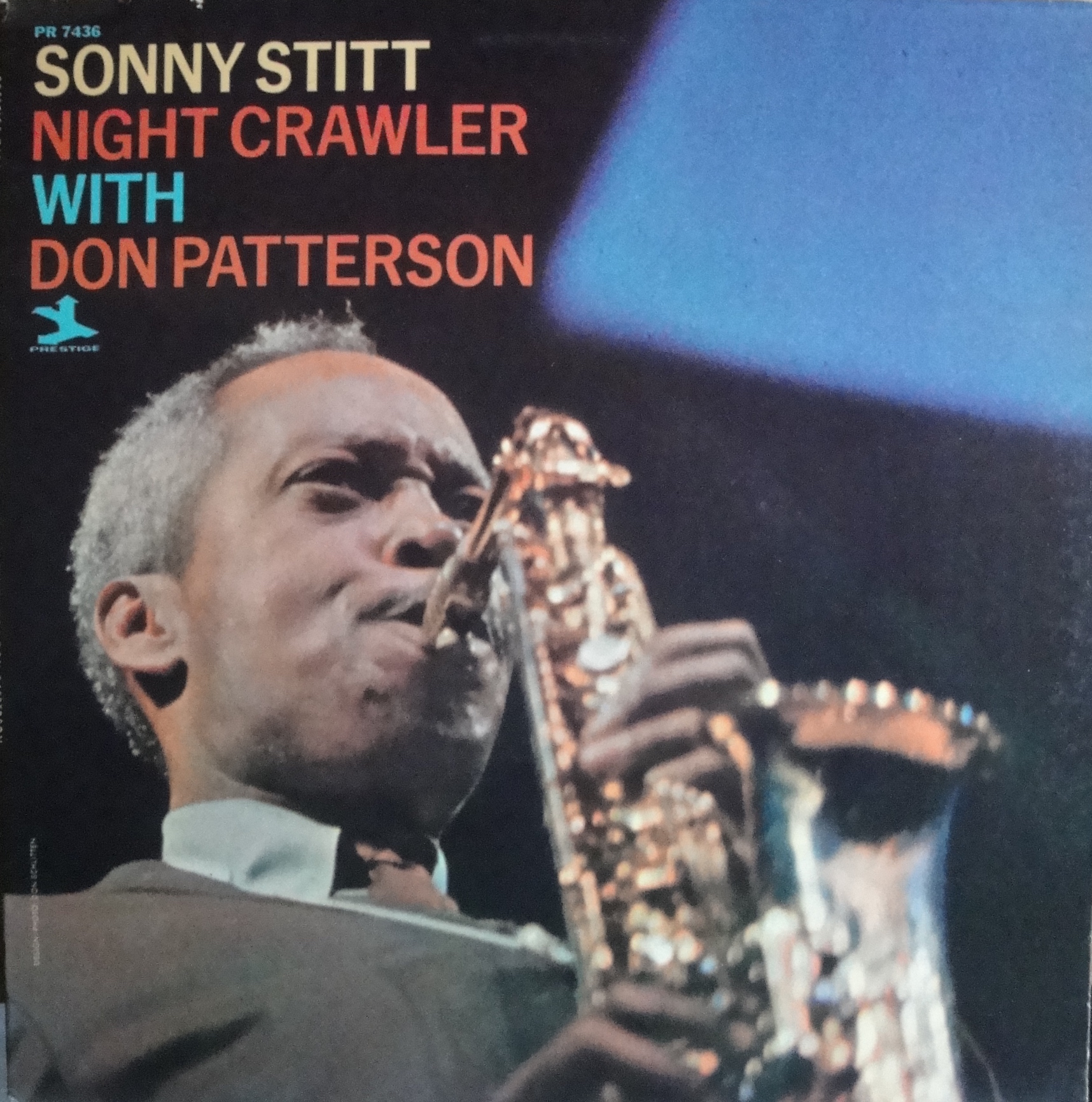

Sonny Stitt Night Crawler (Prestige 1965)

The discography of Sonny Stitt is so vast, it’s bound to include some average affairs. Night Crawler is one of them. It, like much of Stitt’s organ combo work from the sixties, doesn’t possess the brilliance of his bop playing in the fifties or career-defining early seventies work, but sets a good groove. Stitt’s playing, however, isn’t very spirited.

Personnel

Sonny Stitt (alto & tenor saxophone), Don Patterson (organ), Billy James (drums)

Recorded

on September 21, 1965 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7436

Track listing

Side A:

All God’s Children Got Rhythm

Answering Service

Tangerine

Side B:

Night Crawler

Who Can I Turn To?

For a big part, Night Crawler relies on the classic AABA-song structure. Stitt also returns to the well-worn warhorse All God’s Children Got Rhythm. Although not really on fire, Stitt’s beautiful execution nevertheless is a thing to be treasured.

Stitt’s delivery on alto is ultra-clean and bop’s signature techniques such as double timing and the trading of fast fours are played in a seemingly effortless manner. Night Crawler being the one funky blues, it’s not surprisingly chosen as album title. It’s just one of six tracks on which organist Don Patterson displays a wonderful sense of restraint. Night Crawler is part of a series of albums in which this trio cooperates. (e.g. Low Flame, Soul People and Don Patterson’s Funk You) They also were a working band. It explains their smooth interplay.