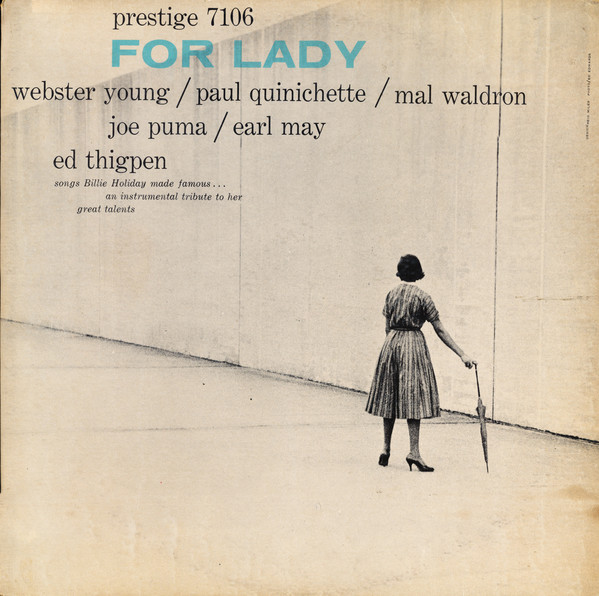

Webster Young found the right touch of melancholy and heartburn on his tribute record to Billie Holiday, For Lady.

Personnel

Webster Young (cornet), Paul Quinichette (tenor saxophone), Joe Puma (guitar), Mal Waldron (piano), Earl May (bass), Ed Thigpen (drums)

Recorded

on June 14, 1957 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as PLP 7106 in 1957

Track listing

Side A:

The Lady

God Bless The Child

Moanin’ Low

Side B:

Good Morning Heartache

Don’t Explain

Strange Fruit

Never heard of Columbia, South Carolina until I read that it is the birthplace of trumpeter Webster Young. He was born there in 1932 but raised in Washington D.C., more familiar jazz terrain, not a major historical jazz center, though the fact that it, besides Leo Parker, Buck Hill, Charlie Rouse, Ira Sullivan and Billy Hart spawned Duke Ellington is significant. New York City is the quintessential modern jazz hub and that is where Young traveled to in the mid-1950’s and hooked up with alto saxophonist Jackie McLean.

Most jazz fans likely discovered the under-recorded Young on the Prestige All-Stars record Interplay For Two Trumpets And Two Tenors, which is routinely sectioned under the name of tenor giant John Coltrane. He’s heard on four records by McLean in 1957/58, among those A Long Drink Of The Blues. While hot shots like Lee Morgan were defining the hard bop field, Young preferred the understated lyricism of Miles Davis, in particular the period of 1954, when Davis recorded Walkin for Prestige and Bag’s Groove for Blue Note. Young’s indebtedness to Davis is furthermore revealed by his composition House Of Davis, featured on Ray Draper’s Tuba Sounds. Moreover, 1961 recordings by Young in St. Louis were released as Plays The Miles Davis Songbook in 1981.

From Columbia, Washington, army band stint with Hampton Hawes, his arrival and recording activity in NYC to For Lady, the story is relatively clear. Thereafter, Young disappeared from the scene. But in 1992, the trumpeter surprisingly found himself on a bill in The Netherlands, touring with fellow unsung trumpet hero Louis Smith and the Rein de Graaff Trio featuring bassist Koos Serierse and drummer Eric Ineke as part of De Graaff’s acclaimed Bop Courses, which included such diverse legends and unsung heroes as Johnny Griffin, Dave Pike, Red Holloway and Marcus Belgrave. De Graaff (on the phone) explains: “The way that I understood, Young left New York because it was such a mess. Back then a big part of New York was very criminal and infested with narcotics. Young was afraid that his life would spiral out of control because of drugs.”

“It all started a year before the gigs in Holland when I was in the US. Trumpeter Tom Kirkpatrick gave me a hint of Young’s wherabouts in Washington D.C. He had moved to Washington because he wanted to earn a living to support the study of his son. Tom told me that Webster was still playing. We met and worked out an understanding for the performances in The Netherlands. He was fragile but played really well and was flabbergasted by all the attention. Fans approached him with LP’s and his music came out of the speakers in clubs, which blew his mind. Unlike Smith, who together with his wife was culturally savvy, Young was overwhelmed by some of our castles and fortresses. He really was like, what is this!”

“At the Bimhuis in Amsterdam, Young started to play When Lights Are Low on his own. That was like hearing Miles Davis in 1954. You could hear a pin drop.”

Young’s excellent playing is confirmed by Eddy Determeyer in JazzNU’s issue of April 1992: “Snow white, tiny and suffering from arthritis, Young focuses on the middle register, a terrain filled with honey notes, soft and warm like lover’s embraces. His timing is challenging and Young fills his choruses with fresh melodies.”

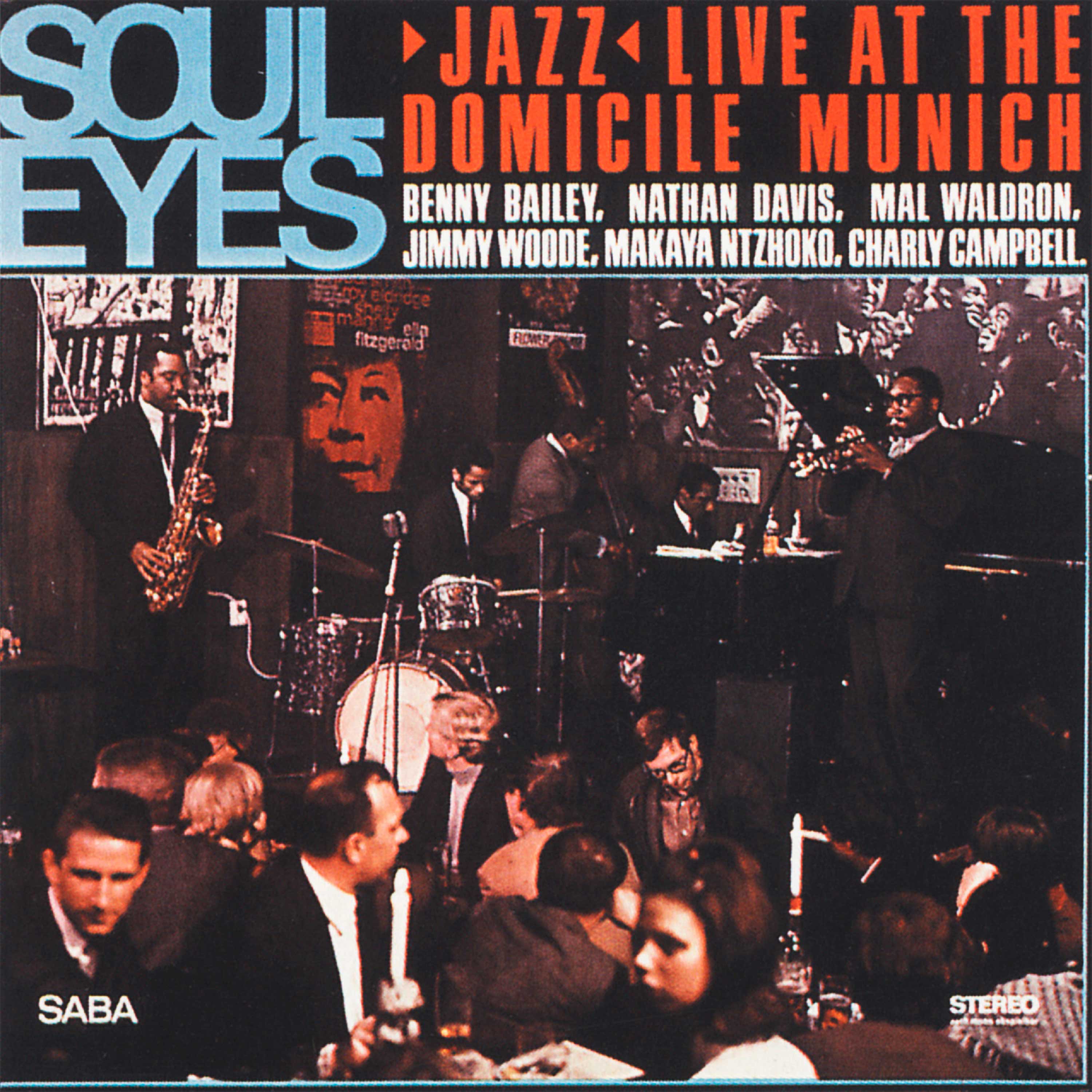

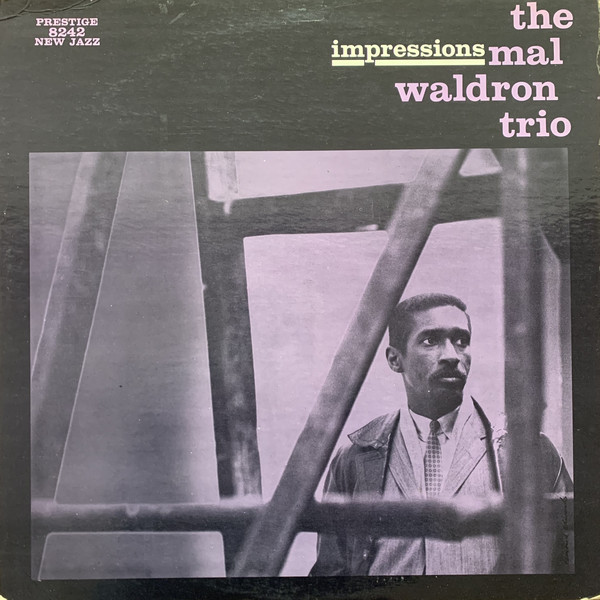

(Left: Rein de Graaff, Louis Smith, Webster Young and Eric Ineke, 1992)For Lady suggests the same pin-dropping power that is referred to by De Graaff. Unlike the bop and hard bop blowing sessions that made up the Prestige catalogue, Young’s sole album as a leader is subdued and moody. Young’s got a great feel for Billie Holiday’s world-weary drama and his performance on For Lady is at similarly stately and blues-drenched. His delivery is at once mournful and defiant. Two of Young’s colleagues are entitled to present a tribute to Lady Day: tenor saxophonist Paul “Vice-Prez” Quinichette and pianist Mal Waldron, both Holiday alumni on stage and in the studio. As a matter of fact, Waldron was Holiday’s accompanist at the time of this recording and would remain so till her death in 1959. Waldron’s own tribute to Holiday, 1959’s Left Alone, is a nice companion piece to For Lady.

Singing the blues is Young’s business and bop is by and large left at the gate. Understatement is key and his tone (on cornet here and incidentally the French cornet that he borrowed from Miles Davis) has the innocence of a young man that’s startin’ out of the gate of big city life, simultaneously vulnerable and assertive. It’s a pleasant mix and one, if you come to think of it, not at all so easily to attain and follow through.

Although Young sounds a bit wobbly on Moanin’ Low, his conception fits God Bless The Child, Strange Fruit, Good Morning Heartache, Don’t Explain and the Young original The Lady like a glove. The inviting opening tune of The Lady is a catchy melody and features typically quirky phrases by Waldron and full-toned, deft contributions by guitarist Joe Puma. Throughout, the smooth and smoky sax of Quinichette effectively turns up the heat a notch after Young’s plaintive stories.

Strange Fruit is a test of sorts. Light swing does not do justice to this story of a lynching, neither does overstated drama, as Nina Simone unfortunately proved much later on. The band’s elegiac treatment is spot on, foreboding drum figures – ‘executioner’s drums’ as liner notes writer Ira Gitler aptly calls it – gradually heighten the tension of Young’s stately homage to Holiday’s natural emotive power. Middle ground is Young’s terrain and he skirts the borders of blues and sophistication very nicely, thank you.