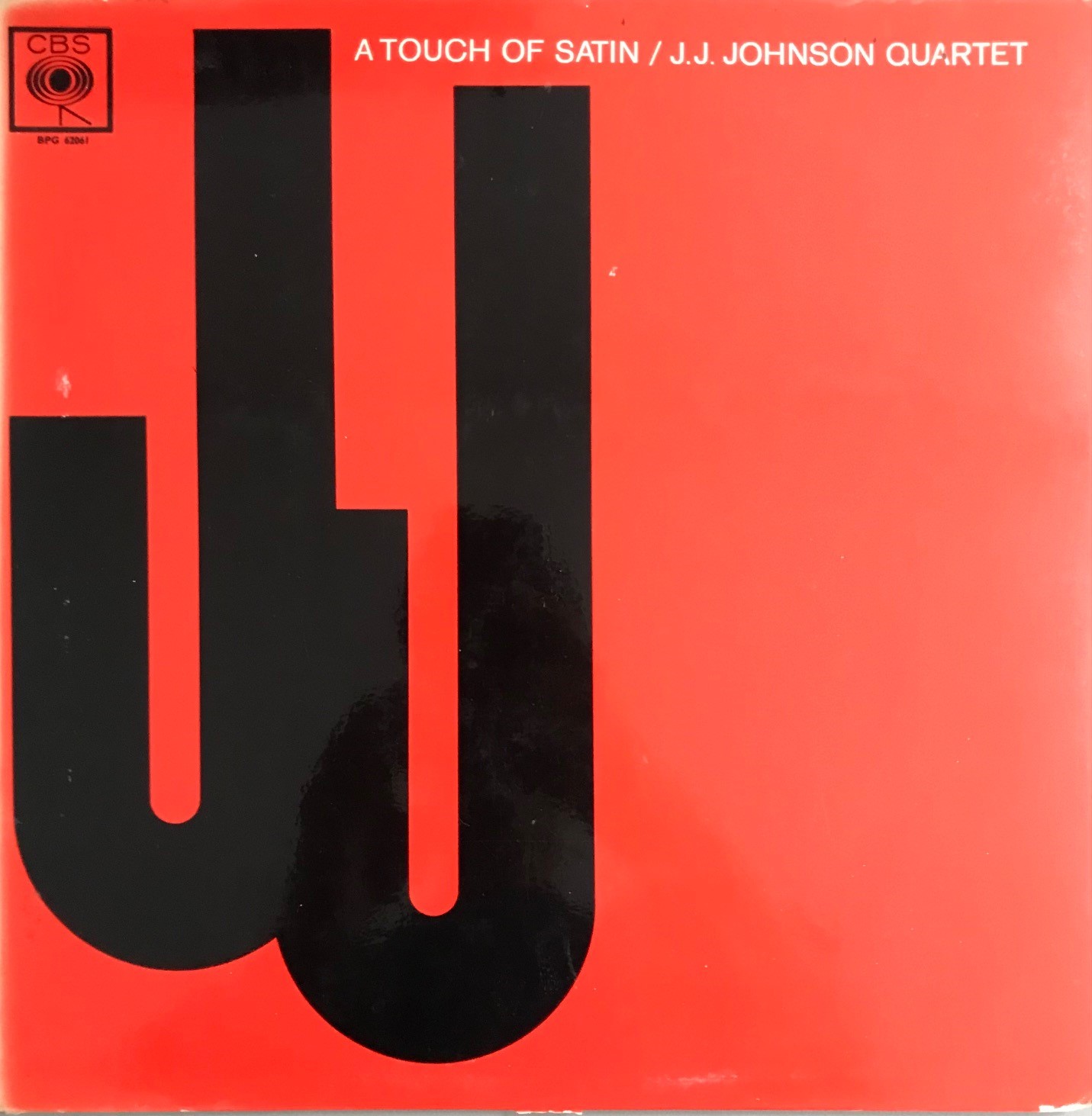

J.J. Johnson and Cannonball’s rhythm section. Ergo: hard bop bone-ology of the highest order.

Personnel

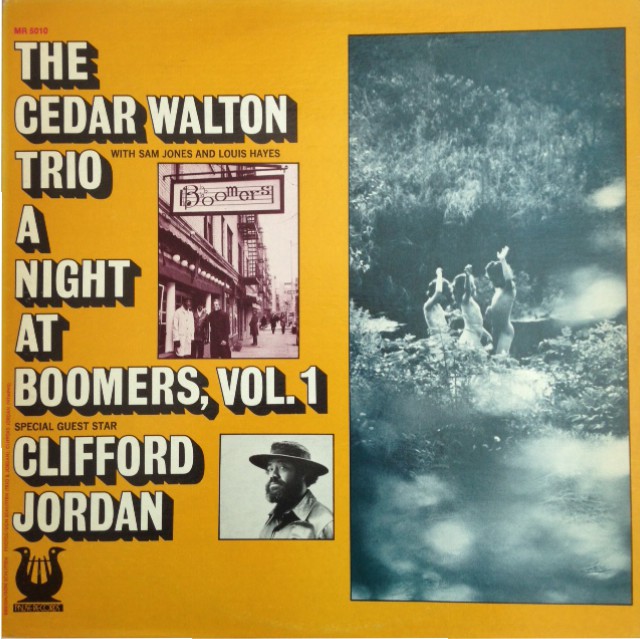

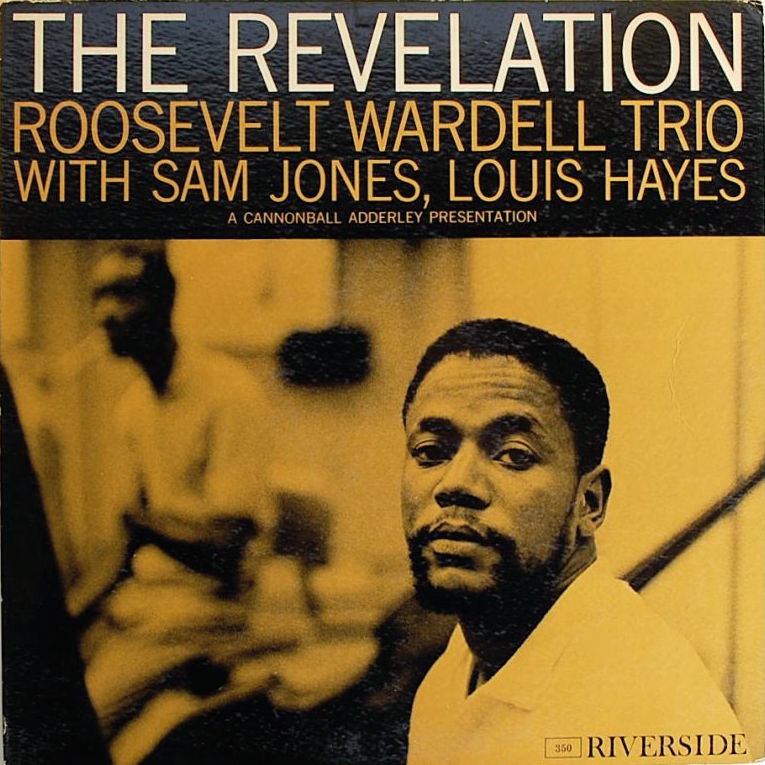

J.J. Johnson (trombone), Victor Feldman (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

Recorded

on December 15 & 21, 1960 and January 12, 1961

Released

as CL 1737 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Satin Doll

Flat Black

Gigi

Bloozineff

Side B:

Jackie-ing

Goodbye

Full Moon And Empty Arms

Sophisticated Lady

When The Saints Go Marching In

Though hardly the greatest recording by J.J. Johnson, it couldn’t go wrong. Simply and curtly stated by Johnson in the liner notes of A Touch Of Satin: “Last year while touring in Europe I had the pleasure of appearing as soloist with accompaniment by Julian “Cannonball” Adderley’s rhythm section. To say the least, I enjoyed the experience the most. So much so that with Cannonball’s approval, we recorded this LP immediately upon returning from Europe.”

By 1960/61, the date of these recordings, the leading modern trombone player, born in 1924 in Indianapolis, had been on the scene for almost twenty years. He went through the bands of Benny Carter and Count Basie and the famous Jazz At The Philharmonic tours from Norman Granz before turning into the pioneer of trombone playing in bebop, an up-until-then unmatched virtuoso that set the template for future modern trombonists. Johnson was a pivotal presence on historic recordings: Charlie Parker’s On Dial in 1947, Stitt/Powell/Johnson in 1949, Miles Davis’s Birth Of The Cool in 1949 and Walkin’ in 1954, Dizzy Gillespie’s Afro in 1954, Kenny Dorham’s Afro-Cuban in 1954 and Sonny Rollins’s Volume 2 in 1957. Meanwhile, Johnson struck up a co-leadership with fellow bone boss Kai Winding, a much-acclaimed duo that recorded successfully from 1954-60 and 1968/69.

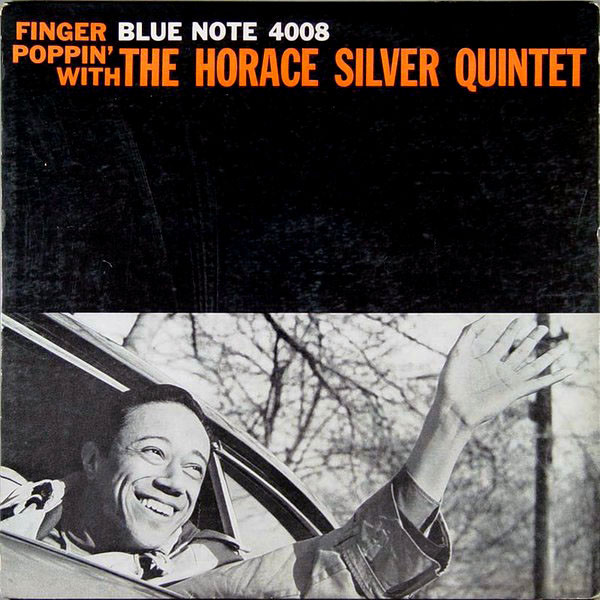

A series of Johnson compositions became instant standards, notably Wee Dot and Lament. Among his records as a leader, The Eminent Jay Jay Johnson Volume 1-3 on Blue Note from 1953-55 are unbeatable, coupling the best of the best as Clifford Brown, Kenny Clarke, Wynton Kelly, Charles Mingus, Hank Mobley and Horace Silver. Johnson found a home at Columbia Records in the mid-fifties and turned out a lot of excellent records for a period of seven years, notably First Place with Tommy Flanagan, Paul Chambers and Max Roach.

A Touch Of Satin isn’t a satin affair at all, nor velvet and neither flannel, but named so because Duke Ellington’s Satin Doll is part of the repertoire. It’s more like a sturdy cotton shirt and a thick wool sweater. He’s certainly reveling in the company and though Johnson maintains his trademark clean and bright tone and would never sound as gritty and greasy as Ellington trombonists or Al Grey, his sound is unusually big and broad and his style features plenty ‘blooziness’, perhaps that the reason why Johnson named one of the tunes on this album Bloozineff.

He adds fresh melodic ideas to Monk’s Jackie-ing, riding the waves of Feldman’s hip and deceptively loose-jointed bundle of chords. Feldman lets notes ring like Christmas bells. Satin Doll is a great group effort, a jolly, big-sounding festivity and Johnson’s slyly timed accents and fabulously structured solo are the icing on the cake. Johnson’s Flat Black, the most “Adderley Quintet-ish” cut, finds him on fire and supple and fast like a leopard on the savannah. Bop and hard bop alternates with a couple of nice ballads, featuring Feldman on celeste, and the party goers are waved goodbye with a sassy and hard-swinging version of jazz anthem When The Saints Go Marching In. Party’s over but we don’t mind the headache, it’s been serious fun.

Johnson also turned his attention to Third Stream music, rather successfully one might add, onwards from the early 1960’s, a contender to John Lewis and Gunther Schuller. In the 1970’s and early 1980’s, Johnson worked almost exclusively for cinema and television in Hollywood. Although he returned to jazz performance thereafter and earned several Grammy nominations during the last part of his career, it seems Johnson was not entirely fulfilled. He had his share of bad luck. His first wife suffered a stroke and Johnson cared for her until her death three and a half years later. Johnson was diagnosed with prostate cancer in the late 1990’s.

Apparently, Johnson died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 2001. A tragedy that is mentioned in all available sources online. Is it true or just conjecture after some kind of ill-fated event? Old friend and former manager of Ray Brown, Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven, says: “I first met him in 1980 when he was touring in Europe with Nat Adderley. I saw him many times in L.A. He was very joyous but at the end of his life he became very negative. He was not the same anymore, I think he was not very happy about his career in general. He wanted to do things in other ways, but he didn’t. I don’t know why exactly he was not happy, because he had a great career. He was a fabulous musician. He lived in Hollywood for almost forty years but went back to Indianapolis a couple of years before the end of his life. He stopped playing and writing and giving news to people around him.”

“It is true. He killed himself. He couldn’t handle the fact that there was nothing that could be done after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He asked his wife to go and buy some books for him. When she came back, she found him. A very sad way to leave this earth and a very sad story.”

Too bad. Still, only one occurrence in an exceptional life lived in the jazz realm.

Listen to A Touch Of Satin on YouTube here