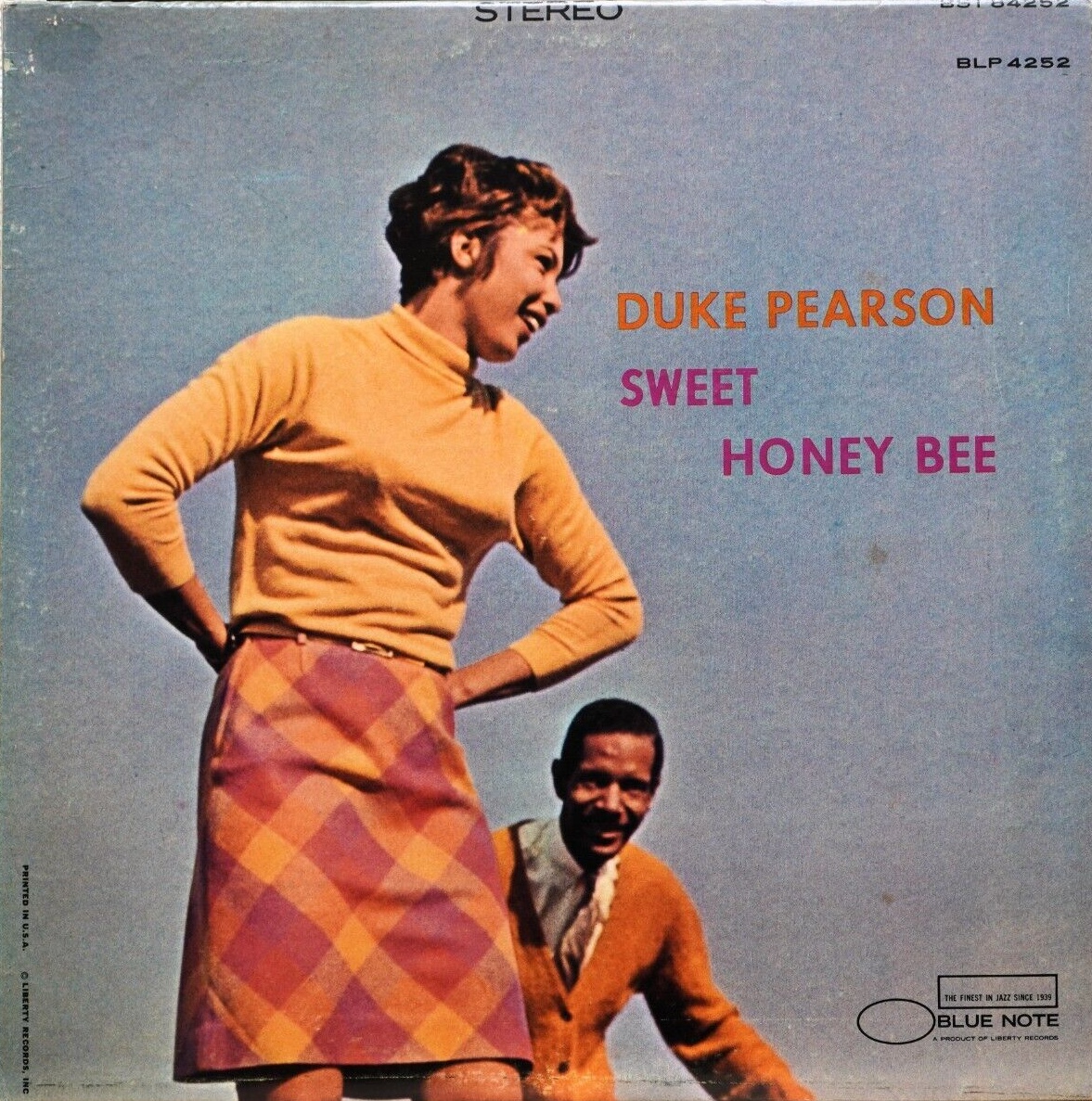

Hard bop was in a rut but Pearson was on a roll.

Personnel

Duke Pearson (piano), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Joe Henderson (tenor saxophone), James Spaulding (flute, alto saxophone), Ron Carter (bass), Mickey Roker (drums)

Recorded

on December 7, 1966 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BST 84252 in 1967

Track listing

Side A: Sweet Honey Bee / Sudel / After The Rain / Gaslight / Side B: Big Bertha / Empathy / Ready, Rudy?

Besides, these traits also apply to his piano and songwriting skills. Somewhat under the radar, not unusual in an era of stellar pianists, Pearson plowed the field of hard bop modernists as Horace Silver and Sonny Clark. Pearson had his own thing going on. Bright solos clear as spring water. A man full of gaiety and the blues.

And a songwriter, damn. He wrote Jeannine. It was recorded excellently by the Cannonball Adderley Quintet. But the essential version is on At The Half Note Café Vol. 2 by Donald Byrd, featuring Pearson on piano.

Pearson wrote Idle Moments for Grant Green’s career-defining session in 1963. And was pianist of service.

Cristo Redentor, The Phantom, Sudel, Wahoo, Chili Peppers, New Girl. Many Pearson songs, great blends of sassiness and ingenuity, not unlike Horace Silver’s compositions, have made a lasting impression. Small wonder that people like to play his tunes. Striking contemporary tributes are The Other Duke by bassist Dave Post’s Swingadelic big band from 2011 and Is That So? by Dutch baritone saxophonist Rik van den Bergh from 2021.

Pearson was a Blue Note recording artist but recorded intermittently for Prestige and Atlantic. He recorded for Blue Note until it was sold to Liberty and co-founder Francis Wolff passed away in 1971. Pearson suffered from multiple sclerosis and died at the premature age of 47 in 1980.

His most adventurous album Wahoo from 1965 is a perennial favorite. Pearson followed it up with two soulful albums on Atlantic, Honeybuns and Prairie Dog. His return to the Blue Note catalogue, Sweet Honey Bee, recorded at the tail end of 1966 and released early 1967, is a sizzling synthesis of groove and lyricism.

By 1967, Blue Note hard bop had become a dinosaur in a world of upheaval that spawned The Black Panthers and the sorrowful cry of Albert Ayler. Yet, Pearson kept the flame burning, seemingly intent on getting the job done. Putting a smile on our face. If records like Sweet Honey Bee don’t make you at least temporarily gay, it seems it’s about time that you order the nails of your coffin. If somebody makes a record like Sweet Honey Bee today, it’ll get a four-star review as a great neo-hard bop album.

Sweet Honey Bee was written for Pearson’s wife. She couldn’t have asked for more. It’s lavender in full blue bloom. It’s a Saint Tropez breeze. It’s killer no filler… But it wasn’t a hit record. There is no reason why, three years after Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder, it shouldn’t have been a hit, what with James Spaulding’s sweet-toned flute melody. No luck. Desperately attempting to reach the top of the charts again after mega-hit The Sidewinder by Lee Morgan, Blue Note opened albums of Morgan, Hank Mobley, Duke Pearson, Andrew Hill, with funky tunes to no avail. Chart success is a mysterious phenomenon.

What is success but a matter of perspective? With all due respect, I’ve heard Taylor Swift singing acoustic guitar songs no better than your average village talent show contestant. In hindsight, successful or not, Pearson recorded his gems for posterity. Like Sudel, a happy marriage of a Carribean theme and Hancock/Tyner-inspired layout. Or After The Rain, an achingly beautiful, melancholic ballad. And Gaslight, somewhat Pearson’s Killer Joe, a lightly swinging walk in nocturnal shadows and a glimpse of neon light, not a care in the world though and not a hustler in sight. Serene, dark night.

Freddie Hubbard and Joe Henderson feel like fish in the water, adapt to Pearson’s bouncy and mellow tunefulness with easygoing but lightly charged solos. Ron Carter and Mickey Roker in the house. Amen.

Listen to Sweet Honey Bee on YouTube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f3Ycbx8TctM&list=PLw9ozJMqRxLbE768Z2sPzgcSjhDcmAC-k