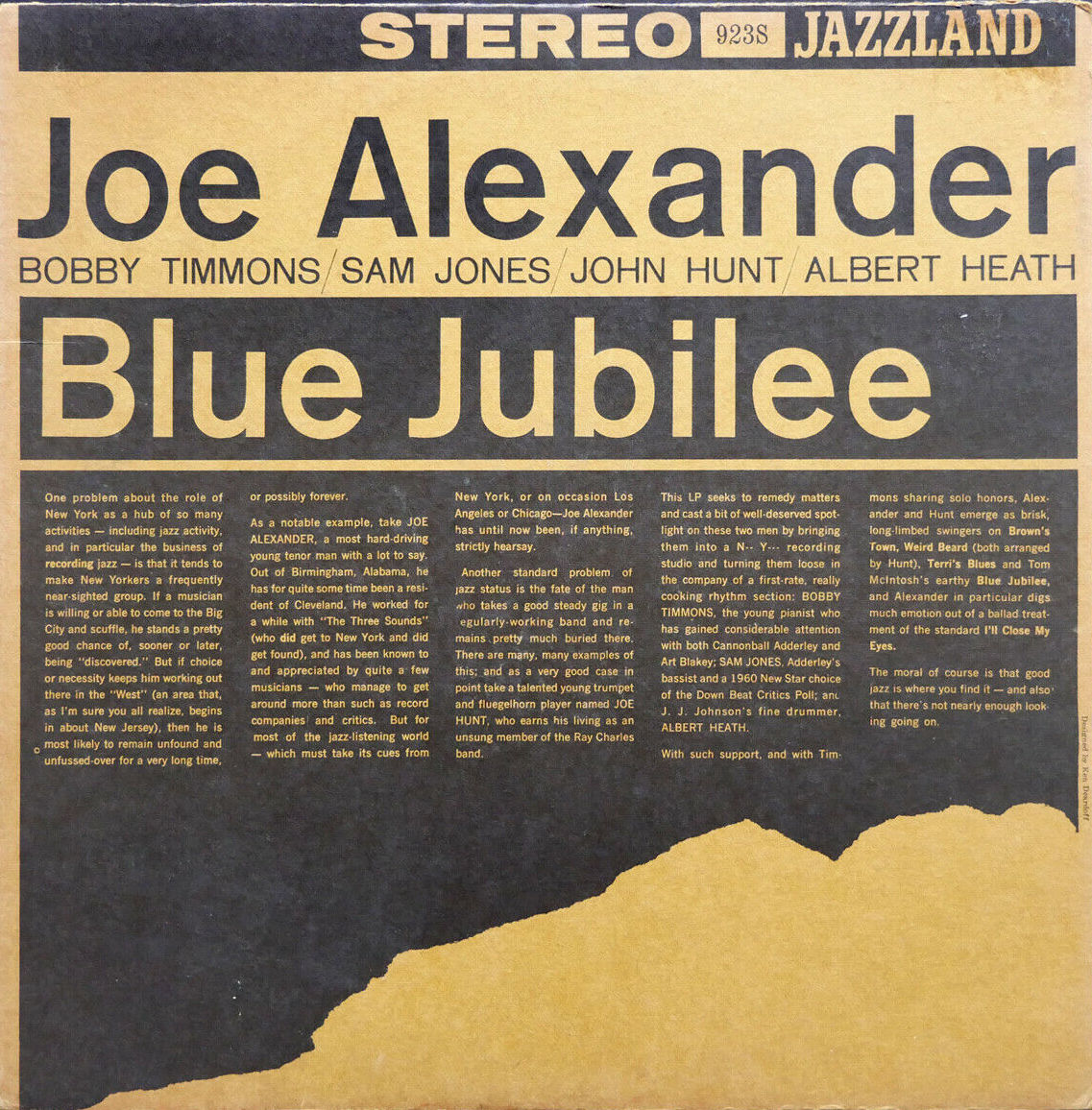

Unsung and acclaimed hard boppers meet for thoroughly enjoyable jazz jubilee.

Personnel

Joe Alexander (tenor saxophone), John Hunt (trumpet), Bobby Timmons (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Albert Heath (drums)

Recorded

on June 20, 1960 at Bell Sound Studios, New York City

Released

as JLP 923 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Blue Jubilee

Brown’s Town

Side B:

I’ll Close My Eyes

Terri’s Blues

Weird Beard

The history of the jubilee goes back to Judaism. Hebrews celebrated liberation from slavery every fifty years. Their concept of the jubilee trickled down to Roman Catholic culture, altered as works of repentance and piety, all the way to religious Afro-Americans who sang songs of emancipation and future happiness. Joe Alexander’s Blue Jubilee, obviously it wouldn’t be red or green or yellow, indirectly refers to the latter practices and its sense of relief and buoyancy is contagious. It’s the only record of the unknown tenor saxophonist from Birmingham, Alabama and a good’n.

And make that two unknowns, since Alexander’s frontline colleague is John Hunt, neither a household name though familiar to diehards as the excellent trumpeter in the Ray Charles band and, a bit later on in the early and mid-1960’s, the group of Charles’s former musical director, saxophonist Hank Crawford. They are supported by Bobby Timmons on piano, Sam Jones on bass and Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums, success guaranteed. The trio – in 1959 and 1960, hit maker Timmons (Moanin’, This Here) had gone from Art Blakey to Cannonball Adderley and back to Blakey, sharing stages with Sam Jones during his successful Adderley stint) fulfills its promise as a front-rank hard bop outfit, clearly enjoying the carefree, blues-drenched vibe. Blue Jubilee radiates with the pleasure of making good-time music together.

Tenor saxophonist with a hard tone, Joe Alexander reminds of Sonny Stitt, though bop figures are less prominent in his bag. John Hunt is a lively trumpeter, no virtuoso but someone who tells little lilting stories, combining one phrase to another with vocalized bends and slurs that enthuse the listener, likely a positive side effect of having limited time to do your thing in the Ray Charles band. Their ensembles are uplifting and they play sassy up-tempo melodies as Hank Crawford’s Weird Beard and Norris Austin’s Brown’s Town, kept interesting by tight-knit stop time rhythm and typical, sparkling gospel-meets-bop solos of Bobby Timmons. Another one who sounds very good is Albert “Tootie” Heath, whose snare beat accents on the mid-tempo blues tune Blue Jubilee, a succinct game of tension and release, properly activate the soloists. Most of all, and thinking back about other recordings, it seems to be typical, Heath sounds so amazingly crisp and urgent. Give the drummer some.

Then there’s the ballad I’ll Close My Eyes, definitely not a fossilized and predictable ritual and marked by a meaty and energetic solo by Joe Alexander. Alexander’s sole recording is a festivity of joy, catharsis and hope very well-spent.