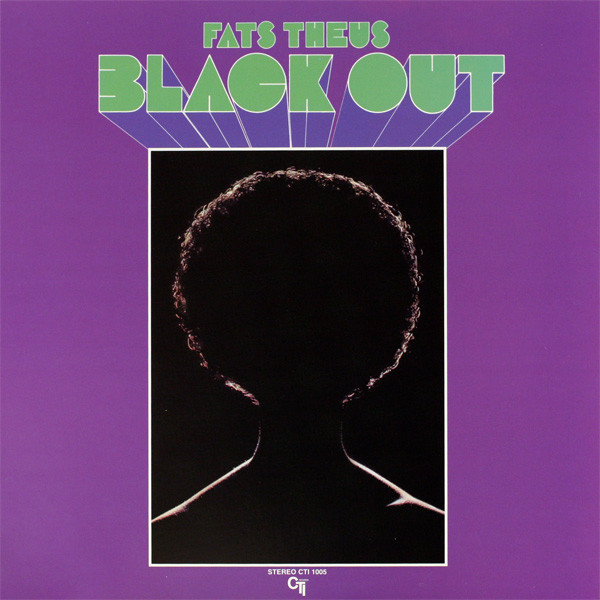

A deviation from the polished jazz catalogue of Creed Taylor’s CTI label, saxophonist Fats Theus’ Black Out is a gritty funk jazz session with the overpowering presence of hard bop and funk jazz heavyweights Grant Green and Idris Muhammad.

Personnel

Fats Theus (tenor saxophone), Grant Green (guitar), Clarence Palmer (organ), Chuck Rainey (bass), Jimmy Lewis (bass), Idris Muhammad (drums)

Recorded

on July 16 & 22, 1970 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as CTI 1005 in 1970

Track listing

Side A:

Black Out

Light Sings

Bed Of Nails

Side B:

Stone Flower

Moonlight In Vermont

Check It Out

Afootnote of the soul and funk jazz era, the life story of saxophonist Arthur James “Fats” Theus remains largely obscure. Originating from the West Coast r&b scene in the fifties, as a logical outcome Arthur James “Fats” Theus cooperated with jazz organists the following decade, including Reuben Wilson. A concise discography reveals (to the knowledge of Flophouse) recordings with organist Billy Larkin And The Delegates (Hold On! – World Pacific, 1965; Ain’t That A Groove! – World Pacific, 1966), organist Jimmy McGriff (I’ve Got A New Woman – Solid State, 1968; The Worm – Solid State, 1968 and Step One – Solid State, 1969) and guitarist O’Donel Levy (Black Velvet – Groove Merchant, 1972). The blues lick The Worm, which Theus wrote for the McGriff date, was a succesful single.

Black Out is one of the earliest CTI sessions (CTI was an imprint of A&M and went independent in 1970) and cousin to the late sixties/early seventies funk jazz sessions on Prestige and Blue Note. Green had made his comeback on Blue Note after his first prolific stint from 1960 to 1965, this time in funk jazz vein, the first being Carryin’ On in 1969. That album also included the organist who’s present on Black Out, Clarence Palmer. Muhammad was a Blue Note and Prestige staple. Green and Muhammad carry the album. The grit and sleaze is in Muhammad’s bones and his funky beat is hypnotic. Green fine-tunes the basic changes with red-hot, articulate phrasing. Theus, albeit clearly operating in their shadow, occasionally does away with his formulaic phrases and jumps from one corner of a tune’s fabric to the other, notably on the title track. Theus embellishes the funky bossa tune Stone Flower with mean staccato phrases and whirling arpeggios.

Theus employs a smooth, high-pitched sound one usually doesn’t associate with late sixties funk jazz. Sound and style-wise, comparing Theus’ leadership date with the saxophonist’s side dates has intriguing results. On the three crackerjack McGriff albums, the Billy Larkin affairs as well as O’Donel Levy’s easy listening funk album Black Velvet, by and large, Theus consistently uses his slightly metallic sound. One is led to consider for a minute that the saxophonist plays the electric Varitone sax, following the footsteps of Eddie Harris and Sonny Stitt. At any rate it has become evident that it’s the signature tone of Fats Theus. Style-wise, Theus fluently adjusts to the bluesy and funky surroundings, yet also throws in a number of excellent, bop-inflected phrases, notably on Easter Parade of McGriff’s big city blues fest Step One LP.

Uplifting funk galore, perhaps Light Sings is the highlight on Black Out. Palmer plays with gusto without being overbearing, Muhammad’s driving beat and propulsive single strokes cause a stir, Green’s liquid silver notes sizzle, his phrases bite and bark. Black Out was Green’s sole appearence on CTI. Much greasier than the slick A&M/CTI albums that star guitarist George Benson was turning in at that time.