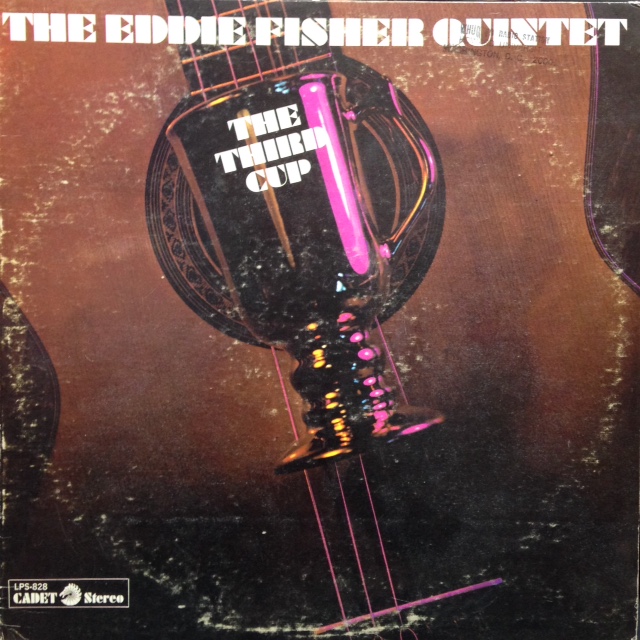

Eddie Fisher’s guitar sound is quite irresistible. Small wonder, then, that his jazzy and soulful 1969 debut on Cadet, The Third Cup, was a good seller.

Personnel

Eddie Fisher (guitar), Phil Westmoreland (rhythm guitar), Bobby Selby (organ), Paul Jackson (bass), Kenny Rice (drums)

Recorded

in February 1969 at Saico Studio, St. Louis

Released

as Cadet 828 in 1969

Track listing

Side A:

Scorched Earth

A Dude Called Zeke

Shut Up

The Third Cup

Side B:

Two By Two

Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Doo-Be-Do-Da-Day

The Shadow Of Your Smile

Eddie Fisher was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1943. The teenage guitarist caught the traveling bug in the late fifties, touring first with Solomon Burke and subsequently stopping by Memphis, Tennessee. There Fisher mingled with Memphis stalwarts Isaac Hayes, Willie Mitchell, Booker T. Jones and Steve Cropper, receiving ample education. Settling in St. Louis in the mid-sixties, Fisher further delved into popular black urban music as guitarist and bandleader with blues master Albert King. Simultaneously, Fisher had honed his skills as a jazz player. In an interview with the Riverfront Times in 2002, Fisher says: ‘I really wanted to play jazz. (…) Albert let me do jazz instrumentals before he came onstage – tunes like Milestones and So What – so I was happy.’

In St. Louis, Fisher got associated with Leo Gooden, the 400-pound club owner, singer and politician and/or hustler who’d been a supporter of guitarist Grant Green a couple of years earlier. (According to Lou Donaldson, Leo Gooden assisted Donaldson and Green to Blue Note headquarter in New York in 1960, to recommend St. Louis resident Grant Green to Alfred Lion; the rest, as they say, is history) Fisher played in Leo’s Five, a group fronted by Gooden in his Blue Note club just out of East St. Louis in Alorton, Missouri. Also in that band were, at different times, saxophonists Fred Jackson and Hammiet Bluiett. Prominent visitors like Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis and Yusef Lateef sat in.

Fisher recorded the 45rpm single The Third Cup on Oliver Sain’s Vanessa label. The considerable airplay of Fisher’s debut on wax as a leader – it sold more than 5000 copies – prompted Cadet, the subsidiary label of Chess Records in Chicago, to release an entire album, also produced by Sain. The Third Cup was a good seller and Fisher’s follow up, The Next One Hundred Years, a big success. Fisher made another album for All Platinum in 1973, Hot Lunch, but then settled down in Centerfield, focusing primarily on social welfare projects with his wife.

On the surface, one may notice the influences of Fisher’s apprenticeship. The horn-like lines, integrated, repetitive blues riffs and blend of relaxation and bite point to fellow St. Louis cat Grant Green. There’s a bit of Kenny Burrell as well, the ease of the warm-blooded blues groove A Dude Called Zeke definitely brings to mind the work of the revered mainstream jazz guitarist. Big city blues, moreover, is in his veins. But, much like blues/jazz guitarists as Freddie Robinson, (although a bit more relaxed) it’s twisted to accommodate a definite, personal style. Fisher’s a fusion cook of note, combining lurid r&b swingers like the uptempo Shut Up and Shoo-Be-Doo-Be-Do-Da-Day, the cookin’ boogaloo tune Two By Two (written, by the way, by fellow St. Louis resident, the future avant-gardist Oliver Lake) with the sick, rock jazz vamp of Scorched Earth.

The group’s take on Harvey Mandel’s The Shadow Of Your Smile is a stiff affair, since subtle swing isn’t the rhythm section’s strong point. The title track is better. The Third Cup travels along the borderland route of soul jazz and CTI-type smooth stuff. It’s also one of the examples of the quintet’s intricate, hi-quality interplay, the contrasting rhythm of drums and bass providing the clever and meaty bottom for Fisher and the excellent organist Bobby Selby to work with. Up front the group’s lively and tasteful accompaniment is Fisher’s unmistakable, plucky, ringing tone. Very alluring.

Eddie Fisher died of prostate cancer in 2007. The Third Cup was finally re-issued properly on vinyl in 2017.