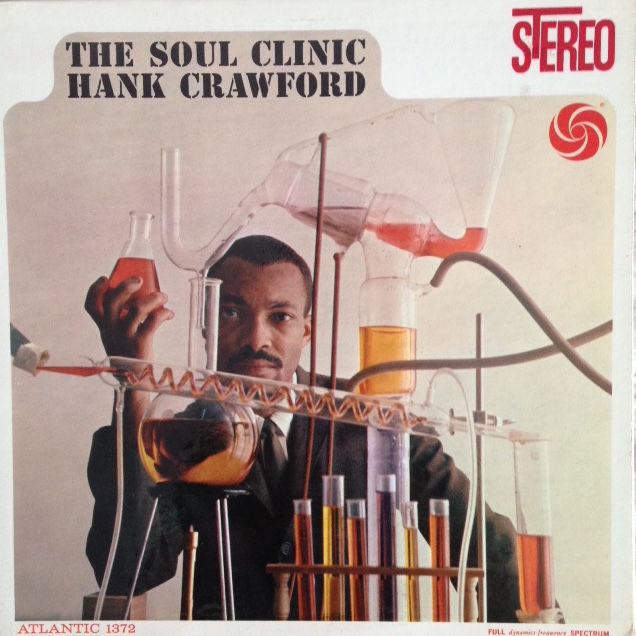

Hank Crawford’s landmark 1962 album The Soul Clinic boasts the saxophonist’s unique, ‘singing’ tone, the swinginest (Ray Charles) band in the land and a mind-boggling trumpet solo by the unknown Philip Gilbeau to boot. Bingo.

Personnel

Hank Crawford (alto saxophone, piano), David “Fathead” Newman (tenor saxophone), Phil Gilbeau (trumpet), John Hunt (trumpet), Leroy “Hog” Cooper (baritone saxophone), Edgar Willis (bass), Bruno Carr (drums), Milt Turner (drums)

Recorded

on October 7, 1960, February 24 & May 2, 1961 at Atlantic Recording Studio, NYC

Released

as SD 1372 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Please Send Me Someone To Love

Easy Living

Playmates

What A Difference A Day Makes

Side B:

Me And My Baby

Lorelei’s Lament

Blue Stone

Pick a winner: Crawford’s

More Soul,

The Soul Clinic or

From The Heart. Good luck. Not that it matters, saxophonist Hank Crawford’s first three albums for Atlantic are equally impressive. It depends on your mood. Bennie “Hank” Crawford, who played alto and baritone saxophone in the Ray Charles band and served as its musical director from 1958 to 1963, went on and recorded more excellent albums for Atlantic in the sixties like

True Blue and

Mr. Blues Plays Lady Soul and churned out hip, down-home tunes as

Skunky Green and

Whispering Grass. Between his Atlantic period and the latter stages of his career spent at the Milestone label with the likes of Houston Person and organist Jimmy McGriff, Crawford switched to a more polished approach on the CTI imprint Kudu. Kudu highlights are

We Got A Good Thing Going On and

Wildflower.

Well, highlights… Sales-and-solo-wise for sure. Wildflower climbed the charts. Crawford’s highly personal style remained largely intact. But production-wise, get a break. His Kudu albums might be your cup of tea but it’s a bottle of snake piss for the Flophouse Floor Manager. Producer Creed Taylor devised a smart formula, which he should be given credit for, but those albums lack exactly what makes the Atlantic albums jewels to be treasured for the ages: the sound of Crawford’s seven-piece band which did much to steer Ray Charles to unforgettable heights.

That sound wasn’t devised out of thin air. The albums feature steady members of the Ray Charles band, a tight-knit group if ever there was one. Crawford coming aboard in 1958 gave the Ray Charles group a big boost, first by his indelible sax playing, soon after by his arranging skills. Consequently, the indirect impact of Crawford on popular music cannot be overstated. The sound of two trumpets, alto, tenor and baritone that Crawford arranged has lingered on in the memories of music lovers as the Ray Charles period to-go-to and became the trademark Crawford sound in the sixties. Effectively, the sound of a modern blues band, one of the last in a line that had been developed onwards from the forties by Illinois Jacquet, Louis Jordan, Arnett Cobb and Bull Moose Jackson. Irresistable outfits.

Up until the 1960 and 1961 sessions of The Soul Clinic, Crawford had appeared on iconic Ray Charles hit singles on Atlantic such as What I’d Say and LP’s as the illustrious Ray Charles At Newport. Crawford shared many duties with David “Fathead” Newman, who went a bit further back with Ray Charles to 1957’s recordings like Doodlin’. Crawford, Newman, trumpeter John Hunt, drummer Milt Turner and bassist Edgar Willis cooperated on the What I’d Say LP, as well as the live album In Person. (minus Turner) Genius Hits The Road includes Crawford, Newman, baritone saxophonist Leroy “Hog” Cooper, Hunt and Turner. Thus, these guys had played, lived and breathed together both in the studio and on the road.

Trumpeter Philip Gilbeau was a newbie in this bunch, who would get his chance to stretch out on Ray Charles’ Impulse album Genius + Soul = Jazz. Drummer Bruno Carr would be part of Ray Charles’ working band on and off in the early sixties. The career of the unknown Carr reveals some interesting associations with, among others, Crawford, Newman, Nat Adderley, Herbie Mann, Dave Pike and Roy Ayers. Finally, Crawford and other members of this line up are also featured on David “Fathead” Newman’s Atlantic albums Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead” Newman and Fathead Comes On. The reason why I go at length to explain the various connections between these musicians is because I feel that the colleagues of Crawford, Newman and Ray Charles are unsung heroes of r&b and soul jazz. Take a deep breath, look at the titles of the before-mentioned albums and singles and let it sink in for a while… Got it?

The way the group builds up a tune is extraordinary. Perhaps by shaking their hips, drummer Bruno Carr and bassist Edgar Willis faultlessly guess the exact amount of small change residing in each other’s side pockets. Locked tight. Fish, hook and line. Ever so slightly, like for instance in the Crawford composition Blue Stone, Carr and Willis stoke up the fire once Crawford’s tenor is getting ready to gain momentum. Much of the album’s charm is brought about by the sonorous arrangements of Crawford. The warm-blooded, transparant production of Tom Dowd chips in magnificently. Except Please Send Me Someone To Love, that includes piano comping by Crawford, the album’s repertoire is piano-less. That worked out beautifully, creating room for the lucid voices of the group’s hard-working gentlemen from the South.

Where can I find a contemporary saxophonist with the kind of one-of-a-kind sound as Hank Crawford? You tell me. Wish me luck. I’d have to take off my pince nez and borrow the looking glass of Sherlock Holmes. Highly unlikely that Hank Crawford is part of the curriculum of the contemporary conservatories. Should be elemental, Hank presents a how-to-find-your-voice course without peer. Off course, not everybody is born in Memphis, main cradle of blues and r&b. But background only doesn’t account for Crawford’s peculiar style. With every repeated listen, awe, hearthy laughter and joy builds up and builds up, until the balloon bursts and tears of joy spray all over the floor. He’s such a stubborn man, doggedly making his point! So convinced of his method and message! Crawford, heard on alto on The Soul Clinic, generally stays close to the melody, points out the bare essentials of the tune, puts it through the wringer until the last drop. Assumingly, Crawford is conscious of every word of the tunes. He tackles the themes with his probing tone and delicate vibrato. A sparse use of fluid bop runs, spicy asides, enhance the bigger picture of his blues-drenched message. Because, essentially, Crawford’s voice is the voice of a blues singer. Not exactly hollering on the fields, Crawford nevertheless unburdens his heart, slightly sweating, sensuously. The sense of hurt is there, he’s been assisting Brother Ray, which obviously must’ve had its effect. But while Brother Ray, when singing the blues, chops out his liver to bleed on the table in front of us, Crawford passes his troubles on a rusty copper plate.

Charlie Parker, the greatest alto saxophonist in the history of jazz, did a thousand things with the blues. The ambidextrous monster musician Steve Coleman, reportedly, dubbed it ‘space blues’. On the other side of the spectrum, Hank Crawford focuses on the core of the blues. But how!

The repertoire is evenly divided between merrily bouncing swingers like the Crawford original Playmates and Horace Silver’s Me And My Baby, gorgeous ballads like Robin/Grainger’s Easy Living and the popular tune What A Difference A Day Makes, which was a hit for Dinah Washington in 1959. The latter is a vehicle for trumpeter Philip Gilbeau. As if Hank isn’t enough to drive you wild, the angels of swing sent down brother Phil Gilbeau. Brash, jubilant, linking Satchmo to crisp modern jazz, Gilbeau’s tale reveals the feelings of a man who loves his woman, which nevertheless left him stranded at a roadside diner after a heated argument. You see him standing outside at the parking lot, one heel on the springboard of his 1958 Packard, swinging a fist, a sudden act of mad laughter that can hardly conceal the yearning, the tenderness, the joy of life. This couple is bound to make up, will be back soon in a barbecue joint, ribs and fries, chili in a bowl, hashbrowns over easy, the whole shebang except candlelight… You hear him think, ‘might be steppin’ into that phonebooth, be callin’ Hank in a minute, just to say I keep-a-rollin’ with my baby…’ Hank understands. The band understands. The guys all sing that song. Not only seperately, but also as the entity that made those albums like The Soul Clinic beautiful, essential, deep blue as the ocean.