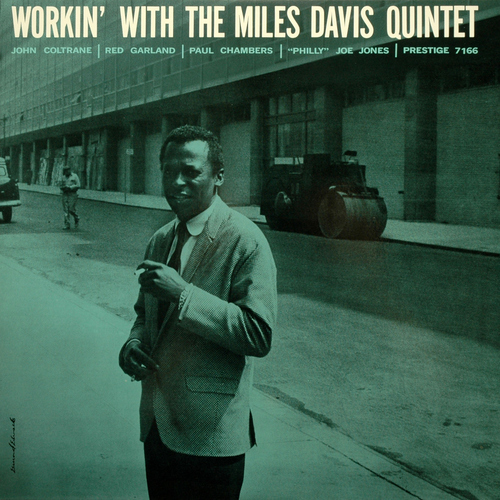

The first two cuts on Workin’ immediately show the impact of Miles Davis (and his First Great Quintet) on the evolution of jazz in the mid-fifties. Davis put the showtune It Never Entered My Mind in a moody package by way of his subdued, husky trumpet. The instant classic Four swings effortlessly but insistently. With a focus on expression, Davis distinctly shaped the kind of jazz labeled as mainstream or hard bop.

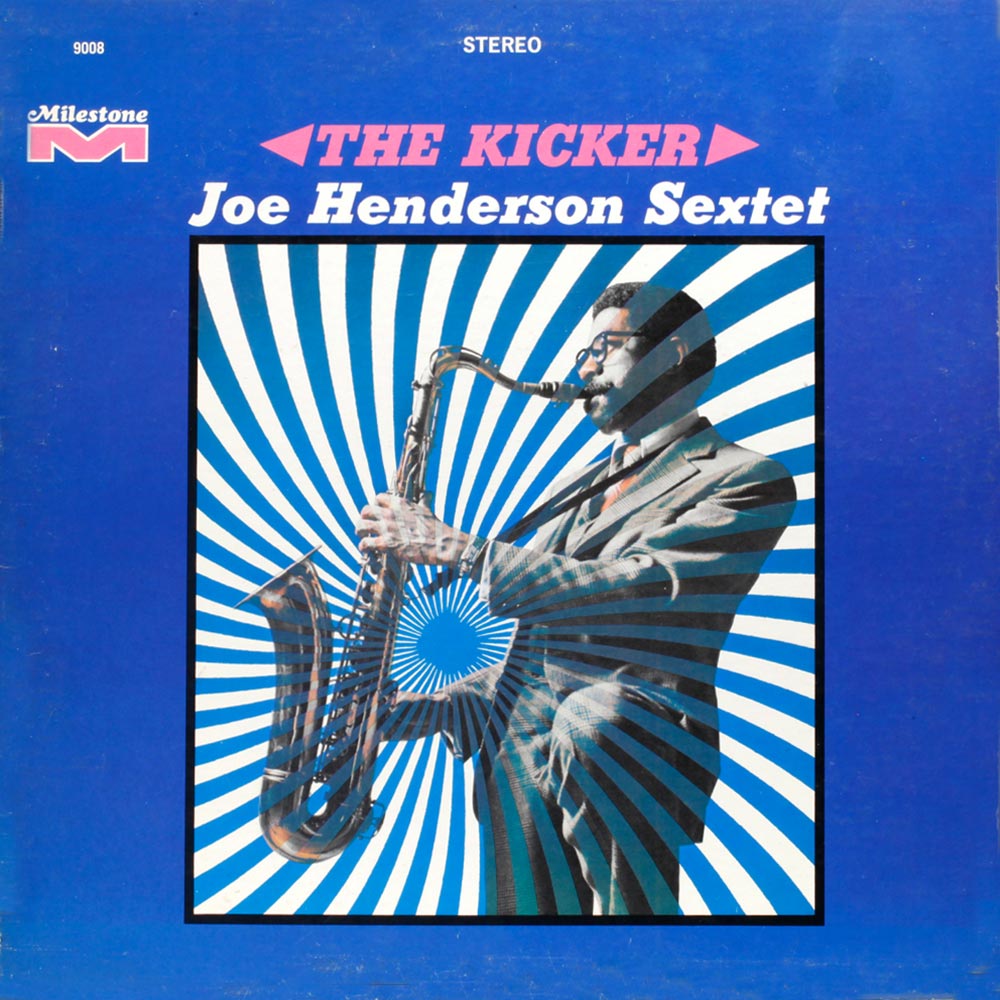

Personnel

Miles Davis (trumpet), John Coltrane (tenor saxophone), Red Garland (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Recorded

on May 11 and October 26, 1956 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7166 in 1959

Track listing

Side A:

It Never Entered My Mind

Four

In Your Own Sweet Way

The Theme (take 1)

Side B:

Trane’s Blues

Ahmad’s Blues

Half Nelson

The Theme (take 2)

When I was young, stupid, sloppy drunk and just about to metamorphose into a giant insect, I used to propagate the opinion that Miles Davis sounded like a door who had trouble creaking. I wasn’t quite fond of his (Harmon) mute sound. In hindsight, I’m sure it was also my cheeky, cynical way of questioning the overdone worship of the ‘Miles’ disciples. Guys in front of the stage begging for the styrofoam cup that Miles Davis drank from after finishing his take on Cindy Lauper’s

Time After Time. Guys that wouldn’t have minded if Miles Davis’d filled it with some of his urinal artistry.

Regardless of the swagger, that door obviously did make a tentative attempt at showing off its creaking prowess. Arguably, the term ‘ugly beauty’, like the title of the Thelonious Monk tune, appropriately defines the muted Miles Davis sound as opposed to his open horn sound. Sometimes it hurts the ear. But that, perhaps, was the inevitable consequence of the goals that Davis set for himself. His acerbic, thin trumpet voice brings about a distinctive feeling. There’s more than a touch of hurt in the playing of Miles Davis, mingling with a distinct soft spot. Understated drama. Simultaneously, his sound has the utmost seductive quality as if it’s the voice of a loose woman peeping from behind a red velvet curtain… A slightly shabby woman, streetwise like any one con man on the corner. So there’s hurt, tenderness and a touch of seediness. More than anything else, listening to Miles Davis at his husky best is like being involved in a conversation of the utmost intimate level. Davis at his thinnest still annoys me from time to time. I wonder if anyone else has been having a beef with the nasal Miles Davis sound? At any rate, I do pretty well today as far as the muted Miles Davis is concerned. (Someday My Prince Will Come!) Times-a-changin’, people-a-changin’ and opinions and feelings seem to change by the minute nowadays. About the only thing that doesn’t change is the quality of Italian espresso.

Not being taken in immediately by the muted sound of Miles Davis, when Clark Terry, Donald Byrd or Lee Morgan were somehow more accesible, the admiration for the notes and vision consequently took some time coming. There’s something to be said for a slowly developing admiration, ripening year after year, like the timbre of a grand piano. The clarity of his ‘voice’ and the way Miles Davis shaped phrases and usually concentrated on fewer, expressive notes, thereby cleverly making use of his strong, individual points, is enough to make one look back in awed wonder. In the mid fifties, starting off with 1954’s recording of Walkin’, Miles Davis breathed musical life into the motto of ‘less is more’ (which was first posed by modernist architect Mies van der Rohe in the 1930s), opening up jazz in an original, interesting direction for the second time in his career. Davis later claimed that he changed the course of jazz five or six times. Which makes sense but wasn’t entirely accurate.

The first milestone would be the Birth Of The Cool-session of 1949. Thereafter, the modal Kind Of Blue, the albums of his Second Great Quintet in the mid-sixties, the fusion of Bitches Brew, jazz rock of Jack Johnson and eighties crossover album Tutu are influential classics. They’re also cases in point that Miles Davis didn’t shake all this innovative stuff out of his sleeve as the sole master for all those years, but instead also relied on such brilliant vanguard colleagues like Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, Teddy Charles, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Marcus Miller. It’s a notion that matches well with the theory that jazz innovations usually don’t come out of the blue, but are the result of a gelling of jazz spirits influencing one another with their simultaneous experiments. Furthermore, often some of these musicians got their ideas from cats they had never even met in (or outside) the studio, like for instance George Russell, or (modernist) classical composers. A valid theory. Superimposing his one-of-a-kind style over the contemporary developments, Miles Davis was crucial to let such profound changes in jazz come to full fruition. He was a catalyst with guts and vision. At the same time, due to his stardom, Davis became the face of that change for the general public.

Long before these kind of elaborate and almost stupefying discussions, in 1956, the one major upset was the signing of Miles Davis to major label Columbia. A big deal not only for Miles Davis but for the Afro-American community in general. Davis, under contract to Prestige, had the agreement that he could record for Columbia and get albums released once his Prestige contract expired. (The first Columbia release would be the Quintet’s 1957 album ‘Round About Midnight) To fulfill his obligations, Davis and Prestige label boss Bob Weinstock agreed to get it over with and record a couple of spontaneous cuts. The sessions of May 11 & October 26, 1956 led to the release of Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’ and Steamin’. Great blowing sessions that showcased the exceptional abilities of everyone involved.

Although an easy way out, Bob Weinstock did took care of structuring the hodgepodge of tunes into a logical order of tracks. He included studio chatter, which was symbolic of the loose atmosphere. (the usage of the two short ‘Themes’, a common jazz practice to start and finish live performance sets, also contribute to that atmosphere) It’s impossible to subdue a smile when Miles Davis announces Trane’s Blues with his gruff, raspy voice. Davis and Coltrane have different ways of dealing with the blues. I feel that Coltrane’s confidence in this tune overshadows the tentative steps of Davis. Nevertheless, Davis’ blend of stacked blue notes and deadpan off-center turns is intriguing.

Davis had recorded Four for the first time two years earlier. It was released on the 10-inch Miles Davis Quartet (Prestige, 1954) and the 12-inch Blue Haze. (Prestige, 1956) The solo on that version is the one people have been crazy about ever since, and small wonder! (Listen Here) Miles Davis is also in very good form on the Workin’-version. Coltrane blows tough tenor, eschewing fast flurries of notes in favor of a more relaxed approach, undoubtly under the influence of Davis. Davis re-visits another tune, Half Nelson. It was initially recorded in 1947 under the guidance of Charlie Parker by the Miles Davis All Stars on a 78rpm Savoy single. (and subsequently under Charlie Parker’s name) The group suavely and swinging flies through the infectious uptempo bop tune.

Ahmad’s Blues – a tune by pianist Ahmad Jamal, who was a big influence on Davis at the time – is a showcase for the rhythm trio. Red Garland stretches out ebulliently on the 32-bar blues with his singular long lines and innovative block chord playing. Miles Davis was enamoured of the tune of another pianist, Dave Brubeck, and seized the opportunity to record In Your Own Sweet Way. Davis initially recorded the tune in March 1956. (Collector’s Items, Prestige) Brubeck recorded it in April, a month after Davis, a solo take on Brubeck Plays Brubeck (Columbia 1956) and a live quartet version appeared on Jay & Kay And Dave Brubeck At Newport. (Columbia 1956) Davis recorded the Workin’-version on May 11. He favored a minor mood over Brubeck’s classical approach and delivered an introspective, smoothly flowing take.

Of the sessions that were released as the Workin’/Relaxin’/Steamin’/Cookin’-albums Miles Davis coolly said: ‘We just came in a blew.’ That’s watertight. It wouldn’t be too much to add, however, that Miles Davis came in and blew in fresh, unique fashion.