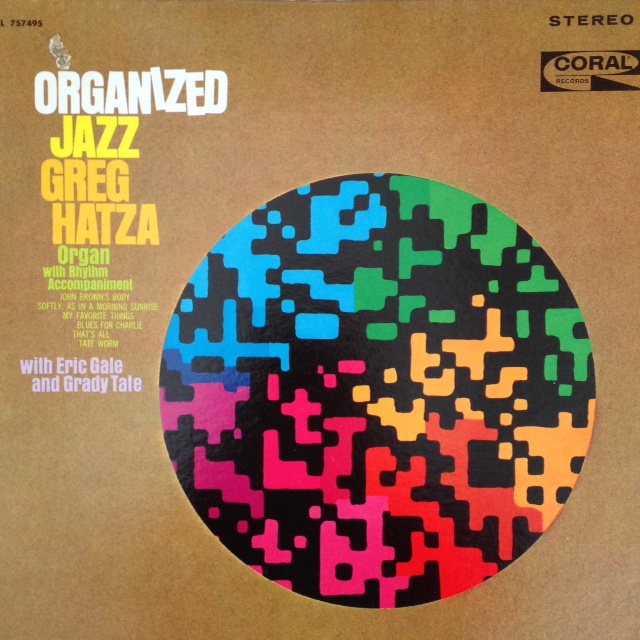

Plenty of sincere and spirited playing on organist Greg Hatza’s 1968 album Organized Jazz.

Personnel

Greg Hatza (organ), Eric Gale (guitar), Grady Tate (drums)

Recorded

in 1968 in New York City

Released

as CRL 757495 in 1968

Track listing

Side A:

John Brown’s Body

That’s All

Tate Worm

Side B:

My Favorite Things

Softly As In A Morning Sunrise

Blues For Charlie

Born in Reading, Pennsylvania in 1948, Hatza’s instrument of choice as a kid was the piano. He switched to the Hammond organ in 1963 under the influence of Jimmy Smith, like so many of his contemporaries. Relocated to Baltimore, at the time one of many Eastern cities with a thriving organ music scene, Hatza enjoyed a four-year residency at Lenny Moore’s and played with, among others, Jimmy Smith, Kenny Burrell, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Philly Joe Jones, Roland Kirk, Les McCann and Sonny Stitt. Coral, a subsidiary of Decca and later on, MCA, released two albums by Hatza in ’67 and ’68, The Wizadry Of Greg Hatza and Organized Jazz. On both albums, Hatza is accompanied by the seasoned drummer Grady Tate and the promising guitarist Eric Gale.

Undeservedly, the albums went largely unnoticed. Surely, Coral, with its roster of Al Hirt, Pete Fountain and Buddy Greco, wasn’t exactly tailor-made for a modern jazz organist. In general, Hatza came up in a period when most organ seats at the larger independent labels were taken by the accomplished players and the popularity of organ jazz slowly but surely started to decline. In the early seventies, Hatza took up bebop piano playing again and switched to the electronic keyboard, performing and releasing albums with his fusion outfit Moon August in the late eighties and early nineties.

Meanwhile, Hatza held raga piano concerts, had been schooled as a sitar, tabla (Indian percussion instrument) and erhu (two-stringed Chinese fiddle) player and developed as a martial arts master, notably in Tai Chi, Shotokan, Pa Kua Chang, Hsing-I and Shaolin Kung Fu. Jimmy Smith’s dabbling in karate pales in comparison. In the mid-nineties, Hatza met organist Joey Francesco, who pointed out to him the resurgence of the Hammond organ’s popularity in a jazz context, and subsequently Hatza resurfaced as a recording and performing Hammond organist with his group Greg Hatza ORGANization, which is active to this day. Hatza also performs with the jazz/gospel group Sanctuary.

Organized Jazz offers an excellent reading of popular song, standards and blues. Hatza’s continuous flow of John Brown’s Body is striking. He’s spicing his solo with lurid, fast-paced bebop figures and makes controlled use of the so-called ‘drone’, which involves the simultaneous climactic use of a sustained chord or note played with one hand and lines dancing through it with the other hand. The trio stretches out on three tunes. My Favorite Things, paramount in the continuous development of John Coltrane and never the same again since, is a surprising pick. The trio succeeds in keeping up a good groove. One of Hatza’s talents is to take his colleagues on a furious drive on the freeway with his pithy statements. It comes to the fore particularly well on My Favorite Things.

Hatza wrote two original blues lines for the album. Showstopper Blues For Charlie possesses some of Hatza’s most passionate phrases. Hatza’s mix of age-old blues licks is peppered with dissonant notes and his timing, precise and varied, is quite out of the ordinary. The tune is also a playground for the upcoming guitar player Eric Gale. Throughout the album, Gale contributes funky, fecund lines.

The title of Tate Worm is a witty reference to the recently deceased drummer Grady Tate. Hatza attacks his mid-tempo r&b-ish line like a young bull storming into the arena. The torrents of notes are like the quick, unpredictable movements of the bull’s horns. To be sure, the bull is possessed with the abandoned desperation of a creature that wants to show who’s boss. Alas, he isn’t. The bull is a victim of the crowd. Perhaps the brazen Hatza doesn’t present the most mature of jazz statements at this stage of his career. However, Hatza’s discography offers abundant proof of his growth as a jazz musician. In 1968, he was a promising, exceptional organist and his second album, Organized Jazz, an effective example of his skills and love of the Hammond organ tradition.

Both The Wizadry Of Greg Hatza and Organized Jazz are out of print, unfortunately. Listen to the Greg Hatza ORGANization on Spotify below.