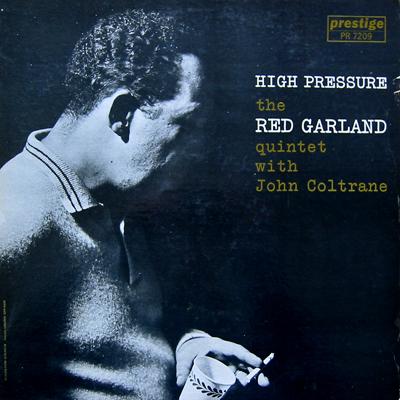

The Red Garland sessions of November 15 and December 13, 1957 spawned a number of Prestige releases. Initially, only All Mornin’ Long was released. Soul Junction came out in 1963 and High Pressure a year earlier, in 1962. High Pressure is a top-notch blowing session, memorable for Red Garland’s influential piano playing and our understanding of the rapid, exciting evolution of John Coltrane.

Personnel

Red Garland (piano), John Coltrane (tenor saxophone), Donald Byrd (trumpet), George Joyner (bass), Art Taylor (drums)

Recorded

on November 15 and December 13, 1957 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as PRLP 7209 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Soft Winds

Solitude

Side B:

Undecided

What Is There To Say

Two Bass Hit

At the time, Red Garland and John Coltrane were colleagues in Miles Davis’ group, which included Philly Joe Jones and Paul Chambers. It was Davis’ first great quintet that recorded the landmark hardbop albums

Miles,

Workin’,

Cookin’,

Relaxin’ and

Steamin’. These albums were scheduled to let Davis fullfill his contract with Prestige, whereafter the group could record Davis’ Columbia album

‘Round About Midnight. Red Garland was fired by Davis, who alledgedly had enough of Garland’s narcotics abuse and erratic behavior, but Garland returned for the session of

Milestones. There was a musical conflict during the recording of

Straight, No Chaser and Garland walked out for good.

Soft Winds, taken at a brisk medium tempo, is essential Red Garland. Garland’s solo is a sumptuous blend of bop and blues, distinctive for Garland’s trademark block chord technique and extended, imaginative right hand lines. Never a dull moment in a five minute solo, of which the groove that Garland sustains through locked-hands playing on the three minute mark is especially enticing. Coltrane fires off phrases that attack the mind like lightning bolts hit a roof top antennae. His famous (and back then, infamous) ‘sheets of sound’ are backed powerfully by five note bombs of Garland and Art Taylor. Donald Byrd contributes a nicely contrasting, buoyant bit. The band trades fours before returning to the robustly swinging theme.

Of the two ballads Solitude and What is There To Say, Solitude stands out. The tempo remains slow throughout this rendition, double timing is avoided. It is the hardest way to play a ballad and, arguably, the greatest way. One has to show what he’s got, naked, no trickery. The band does a badass job, both interactively and solo-wise.

Garland stays close to the swing feeling of Robin & Shavers’ 1938 tune Undecided while adorning it with intricate, rollicking phrases. The group blasts through it like a quintet of Joint Strike Fighters.

Two Bass Hit, the Gillespie/Lewis composition, is also the opposite of lame, including a fiery opening (the theme is stated by the trio only) and contributions from the soloists that are evidence of mutual understanding and suggest that there was a relaxed studio atmosphere.

Two and a half months later, Two Bass Hit was recorded for the beforementioned Columbia album of Miles Davis, Milestones. That band (including Cannonball Adderley alongside a no less imposing, more subdued and structured Coltrane) delivers a crispy, coherent and slightly amended take. In which, lest we forget, the wayward leader didn’t contribute a solo.

The association of Red Garland with Miles Davis ended on a sour note. However, sessions like High Pressure make abundantly clear why Davis wanted to play with Garland in the first place.

YouTube: Soft Winds