TONY ALLEN – On May 19, Blue Note will release A Tribute To Art Blakey And The Jazz Messengers by drummer Tony Allen, a digital EP consisting of four Messengers classics including Moanin’. (see here) It’s a teaser for Allen’s forthcoming album dedicated to the indomitable Art Blakey or as he also came to be known, Buhaina. The legendary Nigerian drummer Tony Allen, who together with Fela Kuti is widely acknowledged as the pioneer of Afrobeat, was strongly influenced by American drummers such as Max Roach and Art Blakey. Which comes as no surprise, since Blakey is often seen as the most African of the modern jazz drummers. Although Blakey, who resided in West Africa in the late forties, always insisted that jazz was a purely American music, the similarities of Blakey’s style and African drums are striking. Seen in this light, percussion-heavy Blakey albums as Drum Suite, Orgy In Rhythm and Holiday For Skins might best be viewed as American interpretations of African rhythm. Allen, who has been living in Paris for twenty years, will be performing the music of Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers at Jazz Middelheim in Antwerp, Belgium on August 5, (see here).

Author: Francois

Herbie Hancock Takin’ Off (Blue Note 1962)

With the authority of a seasoned jazz personality, Herbie Hancock delivered his Blue Note debut as a leader in 1962, Takin’ Off.

Personnel

Herbie Hancock (piano), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Dexter Gordon (tenor saxophone), Bob Cranshaw (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded

on May 28, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 4109 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Watermelon Man

Three Bags Full

Empty Pockets

Side B:

The Maze

Driftin’

Alone And I

Astunning hard bop debut that hinted at post bop things to come. Around 1962, front-line hard boppers, particularly at Blue Note headquarters, were steadfastly developing an ear-catching dialect to the language of jazz. In hindsight, it is beautiful proof of the all-inclusive nature of jazz that these developments, plus gospel-drenched hard bop, plus the major happenings of the day (the envelop-pushing of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Bill Evans), ran a simultaneous course. The stakes were raised and young Hancock wasn’t about to perform below par. His confident playing and composing amidst a bunch of top-rate, contemporary players, including ‘comeback’ legend Dexter Gordon, is striking.

A year later, Miles Davis, another major jazz force, would ask Hancock to join his group, the stellar one which included Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter and Tony Williams. Jazz at a peak, not least because of Hancock’s innovative harmony, voicing and rhythm. During his period with Miles Davis, as is well documented, Hancock himself would deliver albums on Blue Note that defined the post bop style and remain influential to this day, notably Empyrian Isles in 1964 and Maiden Voyage in 1965. A succesful career path was laid out that would include the fusion of his Mwandishi group, the jazz funk of Headhunters and much, much, celebrated more up until the 21-st century’s schizoid present.

Clearly, an experimental spirit had fared into the bespectacled Hancock who peered at your open zipper on the cover of Takin’ Off. It depicts a gentleman whose attire oozed the impression of a kid that fills his evenings with chemistry tests in his granny’s attic. At the dawn of the sixties, the prodigy was taken under his wings by trumpeter Donald Byrd. Prior to Takin’ Off, Hancock debuted as a recording artist on Byrd’s Royal Flush, followed by the Donald Byrd/Pepper Adams Quintet’s Out Of This World and Byrd’s Free Form.

Takin’ Off’s opening cut, the gospel-tinged groover Watermelon Man (turned into a hit by Mongo Santamaria soon after Hancock’s release), sounds as fresh today as in 1962. Many highlights: for one, the infectious rhythm of Billy Higgins is unforgettable. A gritty vibe without the use of the backbeat. Could it be that the island blood in Higgins’ veins accounts for his inventive rhythm? (Other drummers had Carribean ancestors, among them Denzil Best and Mickey “Granville” Roker) Billy Hart (coincidentally, the drummer of Hancocks Mwandishi group) offers a welcome view in an interview with Ethan Iverson on his Do The Math blog. Hart remembers asking Billy Higgins repeatedly about the ‘Higgins island flavor’. Higgins always answered matter-of-factly: “I studied with Ed Blackwell, you know.”

Dexter Gordon’s carefully crafted, behind-the-beat blues story is also a big treat. It blends well with Hancock’s ready and able piano comping, while Hancock includes in his poised solo a number of gorgeous, rollicking cadenzas suggesting both Earl Hines and Maede Lux Lewis. The sound of the piano is round, transparent and upfront, as if Hancock’s playing beside you at the bar. Splendid acoustics at the high-roofed joint in Englewood Cliffs, courtesy of the recently deceased master of modern jazz engineering, Rudy van Gelder.

The inclusion of Dexter Gordon on Takin’ Off has been an obvious delight to many, yours truly included. Gordon, fresh in the act of an iconic comeback on Blue Note in the early sixties after a troubling, preceding decade that was largely wasted on stints in prison (with early May dates Doin’ Alright and Dexter Calling in the pocket) hits a homerun in The Maze, a tacky tune that swings while incorporating McCoy Tyner’s orchestral voicings. This period saw the influence of John Coltrane on Gordon, whose early sides, strikingly, had captivated Coltrane. Insidiously, Gordon’s resonant, fluent solo in The Maze reaches boiling point. Majestic. Trumpeter Freddie Hubbard is his usual sizzling self, raising the stakes with spirited, virtuoso playing. In the ensembles, the forward motion of Hubbard and the nonchalant beat of Gordon create a pleasant, edgy tension that blends well with Hancock’s old-timey yet sophisticated delivery.

Strong points of a flawless, immaculate debut. The chemistry kid had arrived.

Eric Ineke Let There Be Life, Love And Laughter: Eric Ineke Meets The Tenor Players (Daybreak/Challenge 2017)

Crisp and alert drumming on Eric Ineke’s latest Challenge release, Let There Be Life, Love And Laughter: Eric Ineke Meets The Tenor Players. The album brings to life performances of the now seventy year old Ineke with legends like Dexter Gordon and Lucky Thompson, and contemporary colleagues like David Liebman and Grant Stewart.

Personnel

Track 1: Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Rein de Graaff, Koos Serierse, Eric Ineke; Track 2: Dexter Gordon, Rob Agerbeek, Henk Haverhoek, Eric Ineke; Track 3: Johnny Griffin, Rein de Graaff, Koos Serierse, Eric Ineke; Track 4: Grant Stewart, Rob van Bavel, Marius Beets, Eric Ineke; Track 5: David Liebman, John Ruocco, Marius Beets, Eric Ineke; Track 6: Clifford Jordan, Rein de Graaff, Koos Serierse, Eric Ineke; Track 7: Lucky Thompson, Rob Madna, Ruud Jacobs, Eric Ineke; Track 8: George Coleman, Rob Agerbeek, Rob Langereis, Eric Ineke

Recorded

Recorded on October 24, 1984 at De Spieghel, Groningen (track 1); November 2, 1972 at De Haagse Jazzclub, The Hague (track 2); September 16, 1990 at De Brouwershoek, Leeuwarden (track 3); May 17, 2014 at Bimhuis, Amsterdam (track 4); November 20, 2014 at De Singer, Rijkevorsel, Belgium (track 5); October 12, 1983 at NCRV Studio, Hilversum (track 6); November 22, 1968 at B14, Rotterdam (track 7) and April 18, 1974 at Hot House, Leiden (track 8)

Released

as DBCHR 75226 in 2017

Track listing

Body And Soul

Stablemates

Wee

Bye Bye Blackbird

Let There Be Life, Love And Laughter

Prayer To The People

Lady Bird

Walkin’

It is an intriguing and a rewarding project, the combination of so many different styles of tenor playing. In his book co-written with Dave Liebman, The Ultimate Sideman, Ineke, premier European modern jazz drummer who played with numerous legends like Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Mobley and Freddie Hubbard, ruminates on the intrinsic bond between the tenor saxophone and drums: “The tenor saxophone is one of the instruments that is really made for jazz music, much like the trap drums. They are quite similar in that respect. It blends very well with the drums, particularly with the cymbal and with the tom tom sounds.” Ineke swings equally hard with tenorists, altoists or baritone players, yet the conversations of the drummer with Dexter Gordon, Johnny Griffin, et. al. eloquently prove his point. These conversations also are evidence of Ineke’s flexible approach to the manifold ways of phrasing and timing from the classic heroes and contemporary stunners of jazz.

A lot of crackerjack tenorism on Let There Be Life, Love And Laughter. George Coleman, a monster on tenor and perhaps still undervalued, sets fire to the Hothouse in Leiden with Walkin’. A tune that, incidentally, was so influentially performed in 1954 by Coleman’s band leader of 1963/64, Miles Davis, a session that included Lucky Thompson. On this version, Ineke acts accordingly, ‘bombing’ generously and answering Coleman’s staccato, recurring figures equally furiously. Fire and brimstone!

Dexter Gordon’s typically ‘lazy’ but forceful statements on Stablemates, taken from the sought-after LP All Souls: The Rob Agerbeek Trio Featuring Dexter Gordon, are kept in check by Ineke’s steady beat. Gordon wails one of his great solo’s of the seventies. Pushed to the max, another giant of tenor, Johnny Griffin, is flying home at breakneck speed on the bop standard by Denzil Best, Wee. It’s a propulsive high point of the Rein de Graaff Trio, which included bass player Koos Serierse and is marked by high-level bop drumming with a leading role of the ride cymbal. Rein de Graaff’s Bud Powell-influenced solo is ferocious, masterful, the tension is heightened by bold lines up and down the keys. Johnny Griffin is having serious fun. At the end, the Little Giant sardonically and playfully comments on the prolonged Ineke coda: “Shut up! You drummers playin’ so loud. Jazzzzzz music! Where am I, Leeuwarden? Dankjewel.”

On another side of the spectrum Ineke delicately accompanies Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, whose sensuously masculine, breathy take of Body And Soul is most arresting. There’s the clean, round and honestly emotional tone of Clifford Jordan, who plays his original composition Prayer For The People. Lucky Thompson also possessed a lithe, mesmerizing tone on the tenor saxophone. Thompson, an essential link between swing and bop, is heard on Lady Bird on a radio recording at club B14 in Rotterdam in 1968. 1968… where have all the flowers gone: the period in which the professional career of Eric Ineke, who celebrated his 70th birthday recently at The Bimhuis, really took off.

Also from that venerable venue in Amsterdam stems Ineke’s recording (including regulars from his hard bop outfit Eric Ineke’s JazzXpress, pianist Rob van Bavel and bassist Marius Beets, who also took excellent care of this album’s mixing and mastering) with Grant Stewart. His story of Bye Bye Blackbird is relaxed but driving, motivated by Ineke’s lilting rhythm. At forty-six, the Canadian Stewart is the youngest tenor player on the album. Considering Eric Ineke’s supportive attitude towards young Dutch hard bop guys as well as international students on the Conservatory Of The Hague, where he teaches, it would’ve been the cherry on top if a collaboration with a young lion could’ve been included.

On the title song, Ineke cooperates with long-time collaborator Dave Liebman and John Ruocco. During a rendition of the pretty Kurt Weill composition that alludes to the intrinsic Dixie-feel of early Ornette Coleman tunes, Liebman and Ruocco travel a similar avant-leaning path, Liebman with exuberant tinges, Ruocco more introspective. The beat seems to have time-traveled from Baby Dodds to Ed Blackwell to Eric Ineke. A noteworthy excursion to the woods from the hard bop aficionado, who, lest we forget, periodically traveled to modal landscapes with Rein de Graaff and far-out territory with Free Fair in the mid and late seventies.

Let There Be Life, Love And Laughter is a thoroughly enjoyable reminder of the swing and expertise that Eric Ineke has always brought to his gigs with incoming Americans. And I’m sure it will be a revelation for jazz fans who have heretofore been dependant on hearsay.

Find Let There Be Life, Love And Laughter: Eric Ineke Meets The Tenor Players here.

I Loves You, Porgy

PORGY & BESS – Good clubs are a blessing for jazz musicians and, as a consequence, for the audience. Professional equipment, a fine-tuned piano, supportive management and atmosphere are all part of the attraction. Porgy & Bess, the famed jazz venue in Terneuzen, The Netherlands, which celebrates its 60th birthday in 2017, scores way above average. The passionate and welcoming handling of affairs by the team built around general manager Maja Lemmen, who has been associated with Porgy & Bess almost from the start, and the warm-blooded atmosphere are something else. Musicians from all over the world love to perform at Porgy & Bess.

Porgy & Bess was founded in 1957 by the Suriname-born Frank Koulen, who had arrived in Dutch Flanders with the Allied Forces in 1944. It started out as a tearoom but soon staged dixieland, and later on, modern jazz. Koulen, who passed away in 1985, was famous for organising street parades, a novelty in Holland. Porgy & Bess has hosted concerts by Chet Baker, Arnett Cobb, Don Byas, Art Blakey, Benny Golson, Ray Brown, Horace Parlan, Cedar Walton, Phil Woods, Lou Donaldson, Nat Adderley, Lee Konitz, Cecil Payne, Ray Bryant, Toots Thielemans, Philip Catherine, Christian McBride, Danilo Perez, Diana Krall and many others. Simultaneously, Porgy & Bess is a cultural institution that also stages roots music, classical music matinees and literary readings.

Porgy & Bess started off its year of celebration with the return of Porgy regular Roy Hargrove on January 14. In April, festivities continue as Porgy & Bess organizes a Mini Anniversary Festival. On April 20 the Dutch guitarist Anton Goudsmit performs with blues singer Phil Bee, on April 21 Ambrose Akinmusire, one of America’s greatest young trumpet players, performs with musicians from the Conservatory Of Antwerp, April 22 will see a cooperation of the Dutch pianist Bert van den Brink and the Greek pianist/singer Maria Markesini, and on April 23 the Belgian writer Tom Lanoye will mix jazz improv with literature.

For info and tickets, go here.

For my interview with general manager Maja Lemmen, go here.

Photography above: eddywestveer.com

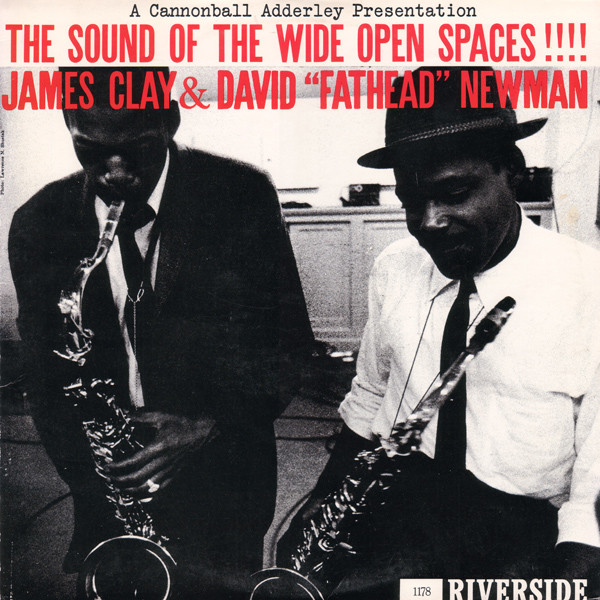

James Clay & David “Fathead” Newman The Sound Of The Wide And Open Spaces!!!! (Riverside 1960)

Some sessions just seem to swing harder than others. The Sound Of The Wide Open Spaces!!!! by co-leaders James Clay and David “Fathead” Newman is such an album. A blast from start to finish.

Personnel

James Clay (tenor saxophone, flute B2), David “Fathead” Newman (tenor saxophone, alto saxophone B2), Wynton Kelly (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Art Taylor (blues)

Recorded

on April 20, 1960 in NYC

Released

as RLP 327 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Wide Open Spaces

They Can’t Take That Away From Me

Side B:

Some Kinda Mean

What’s New

Figger-Ration

Think of the combi’s Johnny Griffin/Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Dexter Gordon/Wardell Gray, Arnett Cobb/Buddy Tate or of the Clifford Jordan/John Gilmore album Blowing In From Chicago. The Sound Of The Wide Open Spaces!!!! (the use of multiple exclamation marks is hyperbolic fancy, but I like the way it looks on the jacket) fits into that high calibre category. Clay and Fathead, two ‘tough’ Texan tenors (and alto’s, flutes) battle it out with the hard-driving support of Art Taylor, Sam Jones and Wynton Kelly. The album was supervised by Cannonball Adderley. Adderley, who had signed with Riverside in 1960 and recorded the highly succesful and influential live album In San Francisco, struck up a good rapport with label owner Orrin Keepnews, immediately getting into fruitful A&R territory.

James Clay is still a relatively unknown saxophonist and flute player. Born in Dallas, Texas in 1935, Clay played with fellow Texan tenorist Booker Ervin, but moved to the West Coast in the mid-fifties. By 1960, Clay had recorded with drummer Lawrence Marable (Tenorman, Jazz West 1956), bassist Red Mitchell (Presenting Red Mitchell, Contemporary 1957) and Wes Montgomery (Movin’ Along, Riverside 1960). As a leader, Clay followed up The Sound with A Double Dose Of Soul, which boasts a great line-up of Adderley alumni Nat Adderley, Victor Feldman, Louis Hayes and, again, Sam Jones. A concise but impressive discography. After contributing to Hank Crawford’s True Blue in 1964, Clay disappeared from the scene, only to enjoy a modest comeback in the late eighties.

Clay’s sound is edgy, his style is reminiscent of bop pioneers like Teddy Edwards. A great match with the better-known David “Fathead” Newman. Newman, the big-toned tenorist from Corsicana, Texas, put his highly attractive, blues-drenched style to good use in the Ray Charles band from 1954-64 and ’70-’71, starring on landmark tunes as The Right Time, Unchain My Heart and albums like Ray Charles In Person and At Newport. Newman was an Atlantic recording artist in his own right. On my deathbed, I’m damn sure I will be remembering Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead Newman (Atlantic 1958) as one of the most soulful albums in modern jazz.

Newman takes the first solo on the furiously swinging opener Wide Open Spaces, taking care of business from note one. He sings, spits, guffaws, presenting a lengthy, driving discourse of blues and bop. Meanwhile, Newman’s phrasing is articulate, fluent, and the full-bodied round tone is intact, and his flow is spurred on by clever, unisono figures of Kelly and Taylor. Clay’s tone is more edgy, thinner. Clay finds solace in darkblue, faraway corners, letting loose occasional gutsy, halve-valve sounds and spices a lively tale with labyrinthian clusters of bop phrases, in a sardonic mood, putting you on, enjoying himself. Then he emerges from the shadows with sudden, belligerent wails. Clay’s a more unpredictable player than Newman. Both take zillion choruses to have their say. Never a dull moment.

Wide Open Spaces is a tune written by the legendary bebop singer and poet, Babs Gonzalez. Figger-Ration, an uptempo, tacky bebop showstopper, is also by Gonzalez. The interpretation of Gershwin’s They Can’t Take That Away From Me is hard-swinging. Keter Betts’ blues-based tune Some Kinda Mean starts with the coda, a raucous figure of snare drums and piano, and develops into a mid-tempo, Ray Charles-type mover. Supported by the responsive, burning rhythm trio of Taylor, Jones and Kelly, the latter occasionally chiming in with ebullient bits on the slower tunes and frivolous strings of high notes on the uptempo tunes, Clay and Newman speak confidently on tenor throughout. For What’s New, Newman switches to alto, Clay to flute. It’s a solid rendition of the well-known ballad.

While a current of pivotal game-changing outings (Davis’ Kind Of Blue, Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Coleman’s Free Jazz) was released in ’59 and ‘60, gospel and blues-based hard bop/mainstream jazz, while not always liked by the critics, was at a peak and admired by audiences around the country and abroad. Hard bop albums rolled off the Blue Note, Prestige and Riverside assembly lines like fortune cookies. That turn of the decade was really something! Something of such all-round excellence which might easily cause such marvelous albums like The Sound Of The Wide Open Spaces!!!! to be lightly snowed under. But it aged well. To this day, Clay and Newman’s bopswinging sax festivities leave one breathless with every new turn on the table.

Sunset And The Mockingbird

JUNIOR MANCE – There were so many great pianists with varying styles in the hard bop era, it demanded endurance and originality to stand out. Junior Mance certainly has an authentic voice. To illustrate his authority among colleagues and label owners, his discography should suffise. Mance cooperated with, among others, Dexter Gordon, Art Blakey, Johnny Griffin & Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, Clifford Brown, Gene Ammons and Cannonball Adderley and recorded prolifically well into the 00’s, his last album being 2012’s The Three Of Us. Mance is eighty-nine years old, but unfortunately, not well. Flophouse received the following e-mail from co-producer Sarit Work about a documentary that’s in the making of Junior Mance called Sunset And The Mockingbird:

I’m producing a feature documentary about the love story of legendary jazz pianist Junior Mance and his wife and manager, Gloria Clayborne Mance. The film is co-directed by Jyllian Gunther (The New Public, PullOut) and Adam Kahan (The Case of the Three-Sided Dream).

Junior suffered a stroke in 2012, which led to the onset of dementia. Though his musical abilities were untouched, his mental and physical decline has forced Gloria’s role to take on a whole new meaning; she is now faced with winding down Junior’s legendary career as he looses his identity — while still, somehow, maintaining her own.

You can watch the trailer here and donate to make possible the cooperation of an editor.

Reachin’ Out To Rob

ROB AGERBEEK/HANK MOBLEY – Just recently, the Dutch Jazz Archive released To One So Sweet Stay That Way: Hank Mobley In Holland. (See review here.) A great document that fills the musical gaps of Mobley’s ten-day stay in The Netherlands in 1967. A big part of the CD is dedicated to Mobley’s gig at Rotterdam’s club B14 with the Rob Agerbeek Trio. More than enough reason to get in touch with veteran hard bop, boogie-woogie and swing pianist Rob Agerbeek and ask about his recollections with the revered tenor saxophonist.

FM: How did that gig came about?

RA: I got a call from a small-time impresario, Wim Johan Kuijper, who asked me: ‘Do you want to play with Hank Mobley? ‘ I said, ‘that’s a silly question! Of course!’

FM: It must’ve been quite something to meet Hank Mobley before the show.

RA: I expected a big, impressive cat, you know. But he was just a young guy. It was a beautiful day, late Winter, early Spring. I was there with my wife. He strolled into the place, threw his horn case into the corner. He asked me, ‘where you from?’ I said: ‘The Hague.’ ‘No’, he said, ‘I mean, where you from?’ Then I got it. I explained that I was born in Dutch Indonesia. ‘Aha,’ said Hank, ‘that’s the place with the king who plays clarinet.’ Almost. ‘No,’ I said, ‘that’s Thailand.’

I was thinking, Jesus Christ, I better set my best foot forward on stage! But it turned out pretty well.

FM: It was a one-off trio, right?

RA: Yes. I hadn’t played with bass player Hans van Rossem. But I was familiar with drummer Cees See.

FM: Was the setlist discussed or did Mobley counted off the tunes on the spot?

RA: Basically, he called a tune and asked if that was ok. Very nice.

FM: The sound quality, quite logically, isn’t fantastic. But you can hear you’re a bed of roses for him, despite the fact that he sounds a bit fatigued as well. You were already a very accomplished player and, naturally, familiar with standards like Autumn Leaves and Like Someone In Love. Mobley’s Three-Way Split was a lesser-known affair. Oddly enough, it’s the swinginest tune!

RA: I knew that tune from the album with Andrew Hill on piano. (No Room For Squares, FM) Yes, Hank liked my playing, afterwards he invited me for a gig to Paris. Sometime later we played at the American School in Paris with Art Taylor, trumpeter Dizzy Reece and bass player Jimmy Woode. Mobley had a session in Paris and wanted me in on it. But Francis Wolff had already booked another pianist, Vince Benedetti. Mobley was rather peeved about being overruled. It turned out to be the album The Flip.

FM: At least now your cooperation with Mobley in Holland is preserved for posterity.

RA: O yeah, it’s a wonderful job by the Dutch Jazz Archive. I’m very honored. I also really like those tunes with the Hobby Orkest.

FM: Mobley in a big band setting, really surprising. The context suits Mobley very well, he’s in great form. It would’ve been really nice if Mobley would’ve done a big band album in his lifetime.

RA: Yes, absolutely. Well, early in his career Mobley did play in Dizzy Gillespie’s band, of course.

Find To One So Sweet Stay That Way: Hank Mobley In Holland here.