Kenny Burrell’s Blue Lights Vol. 1 & 2 consist of a bunch of tasteful, blues-infested tunes. A lively, relaxed jam session.

Personnel

Kenny Burrell (guitar), Louis Smith (trumpet), Junior Cook (tenor saxophone A1, A2 & B1 on Vol. 1, A1, A2 & B1 on Vol. 2), Tina Brooks (tenor saxophone A2, A3 on Vol. 1, A1, A2 & B1 on Vol. 2), Duke Jordan (piano, Vol.1), Bobby Timmons (piano, Vol. 2), Sam Jones (bass), Art Blakey (drums)

Recorded

on May 14, 1958 at Manhattan Towers, NYC

Released

as BLP 1596 and BLP 1597 in 1958

Track listing

Blue Lights Vol. 1

Side A:

Phinupi

Yes Baby

Side B:

Scotch Blues

The Man I Love

Blue Lights Vol. 2

Side A:

Caravan

Chuckin’

Side B:

Rock Salt

Autumn In New York

Kenny Burrell, 86 years old, is one of the great mainstream jazz guitarists, who has been consistently successful ever since he made his debut with Dizzy Gillespie in the early fifties and hit his stride on the Blue Note label in 1956. On the Blue Lights albums, recorded in 1958, Burrell is coupled with other major league players. Drummer Art Blakey, bassist Sam Jones, pianists Duke Jordan/Bobby Timmons, trumpeter Louis Smith and tenor saxophonists Junior Cook and Tina Brooks provide plenty of sparks and a meaty hard bop bottom for Burrell to work with. Fleet, snappy lines, a lot of fresh ideas, articulation best likened to the pop of a champagne bottle, are all in evidence in a set that is comprised of blues-based affairs like Burrell’s r&b groove Rock Salt, the uptempo cooker Phinupi, slow blues Yes Baby, Duke Jordan’s lively riff Scotch Blues, Sam Jones’ choo-choo-boogie-type Chucklin’ and the standards The Man I Love, Caravan and Autumn In New York.

Burrell’s capacity to set the atmosphere, which feels as if he’s wrapping you in velvet drapes, and sustain it consistently, is one of his greatest gifts. His playing is relaxed, but rooted in the blues and not without a topping of sizzle. Vintage Burrell. Perhaps inevitably considering his extremely long discography, I feel Burrell also delivered less inspired affairs that showed a tendency to run through the repertory with safe cliché patterns of phrases. However, especially in the company of hi-level colleagues, like John Coltrane, Sonny Clark or Kenny Dorham, Burrell is at his best. His playing, in those cases, has that extra bit of flair and bite.

Burrell was no stranger to Art Blakey, who drives everybody to the edge of the cliff. Blakey’s ride, it goes without saying, is roaring, a hard drive, a lurid mélange of bombs, cymbal crashes and tom rolls either meant to stimulate the soloist or introduce the subsequent storyteller. Besides Blakey’s boss accompaniment, the drummer’s plush tom variations on the theme of Caravan are striking. The fat texture of brass and reed combines well with Blakey’s forceful style. Smith, Brooks and Cook have ample room to stretch out, and Smith’s gait is sprightly, and he sprinkles his happy blues juices with drops of vinegar.

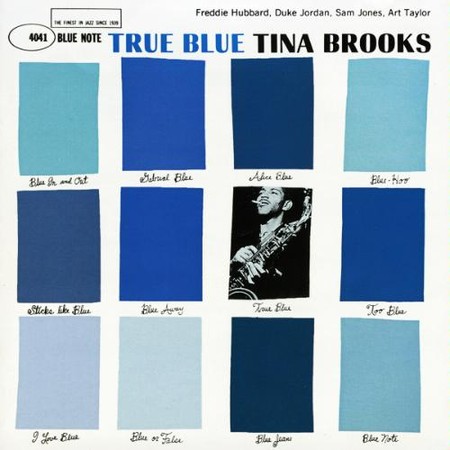

Perhaps more tenor contrast would make Blue Lights more exciting. Both Brooks and Cook are intent on swinging clean, flowing, tasteful, much like master Mobley, Brooks with a tidbit of wear on his notes, Cook somewhat more soft-hued. But who’s to complain? Brooks, who faded into obscurity after a concise stretch of Blue Note appearances, demonstrates the cliché-free, resonant, swinging storytelling that has made him a legend among hard bop aficionados around the world. Junior Cook, who would join Horace Silver late in 1958, provides the tenor sax highlight of the set during Phinupi, the steamy tale and unhurried flow a real treat.

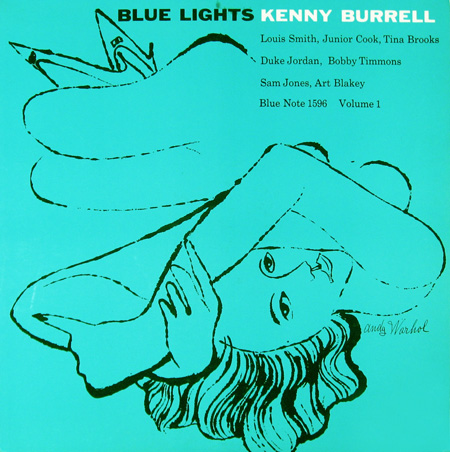

Care to purchase original first pressings of these twin beauties? Good luck. They’re not only at the tail end of the famed and collectable 1500 series of Blue Note, but the covers were illustrated by Andy Warhol, who not only created postmodern mayhem by churning out his screen printings of Campbell Tomato Soup and Marilyn Monroe on the assembly line, but also did his fair yet modest share of record sleeve design. Without a doubt, the Warhol/Blue Lights LP’s are unattainable artifacts for the average collector. Unless, of course, that average collector decides to skip his family trip to Rome and put up a figure of about 1750. A piece. Don’t get any ideas, now.