Hip couple, hip soul. Finding a hip crowd for the collaborations between wife and husband Shirley Scott and Stanley Turrentine was a cinch.

Personnel

Shirley Scott (organ), Stanley Turrentine (tenor saxophone), Herbie Lewis (bass), Roy Brooks (drums)

Recorded

on June 2, 1961 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PRLP 7205 in 1961

Track listing

Side A:

Hip Soul

411 West

By Myself

Side B:

Trane’s Blues

Stanley’s Time

Out Of This World

Organist Shirley Scott released no less than eighteen albums on Prestige from 1958-61, including the subsidiary label Moodsville. Excluding six albums that the company released from 1965-67, when Scott had already become part of the Impulse label roster. Tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, married to Scott in 1961 and divorced in 1971, guest-starred on five albums by Scott on Prestige and Impulse. In turn, Scott was featured on four of her husband’s Blue Note albums.

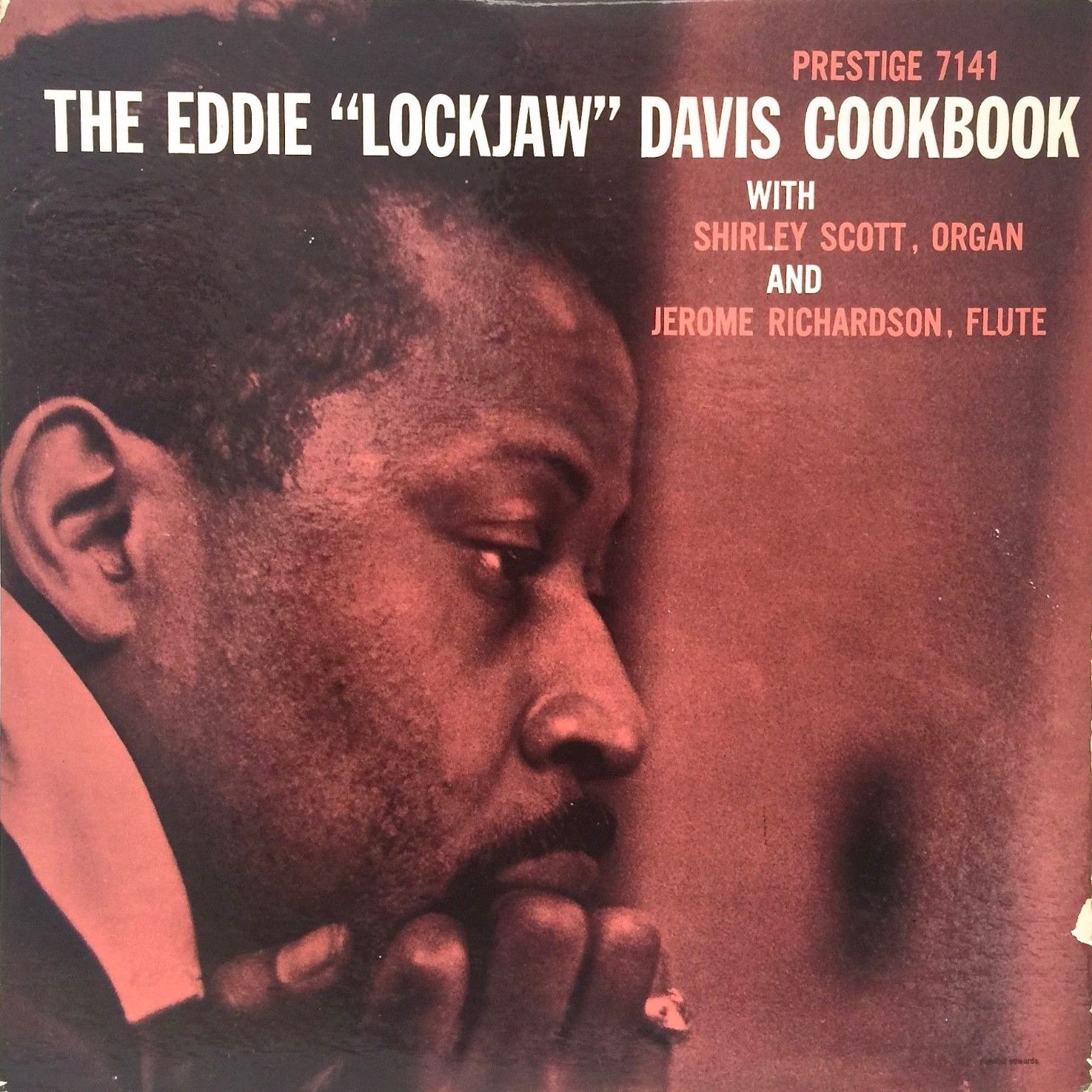

They not only had grown accustomed to each other’s faces on daily bases, meshing musical styles hardly posed a problem. Scott had started her organ combo career with Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and therefore had plenty experience of playing with a highly original tenor saxophonist. The collaboration of Scott and Turrentine is about the blues and a fair share of standards and modern jazz. It comes as no surprise that the prolific recording duo was a popular attraction in the circuit of clubs of the soul jazz era.

The beautiful Shirley Scott looked great on a record cover, and high-spirited. Don’t mess with Shirley. Music-wise, her tasteful, driving playing style demands attention. Largely ignoring the revolution of Jimmy Smith, Scott preserved an orchestral approach during her years on Prestige, the settings of her organ ‘old-fashioned’ almost like Wild Bill Davis, the style full of gospel and swing and with few tinges of bop. It is only during her tenure on Impulse that Scott expands her territory with more elaborate single lines and a more modern sound.

Hip Soul is as good an example as any of the Scott/Turrentine combinations on Prestige. The group, including bassist Herbie Lewis and drummer Roy Brooks, performs the mid-tempo, down-home blues of Hip Soul, the sophisticated melody of Benny Golson, 411 West, the pleasurable standard By Myself, John Coltrane’s (surprise pick) Trane’s Blues, the catchy blues line by Turrentine, Stanley’s Time and Arlen/Mercer’s Out Of This World. Sounds like an appropriate second set at, say, New Jersey’s Club Harlem or Chicago’s Theresa’s Lounge, the crowd in anticipation of another hour of lurid down-home jazz.

They take their time to stretch out during the course of the very enjoyable 11 minutes of Out Of This World. Scott’s solo consists almost strictly of chords, the suspense hinging on voicing, her meaty touch and gospel feeling. Turrentine, the Single Malt of tenor saxophonists, all peat, oak, berries, cutting the phlegm and leaving a layered taste in the palate, demonstrates his unique way of bending blues-infested notes, sometimes stretching them as little but imposing wails, a hypnotizing brew. He swiftly phrases through his finest story of the album.

Stanley Turrentine passed away in 2000. Shirley Scott in 2002.