And the Bentley driving guru is putting up his price, anyone for tennis… wouldn’t that be nice?

Personnel

Stan Getz (tenor saxophone), Eddy Louiss (organ), René Thomas (guitar), Bernard Lubat (drums)

Recorded

on January 11 and March 15-17 at Ronnie Scott’s, London

Released

as V6-8802 in 1971

Track listing

LP1 Side A:

Dum Dum Dum

Ballad For Leo

LP1 Side B:

Our Kind Of Sabi

Mona

LP2 Side A:

Theme For Emmanuel

Invitation

LP Side B:

Song For Martine

Dynasty

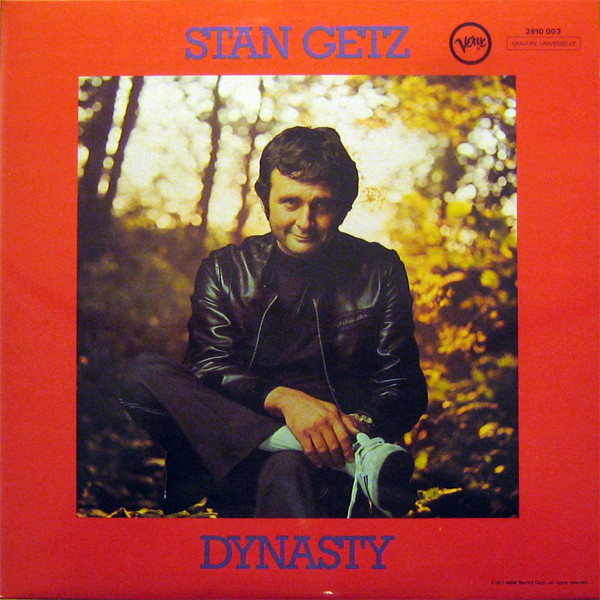

By 1970, Stan Getz had plenty reason to be proud of an already very successful career of approximately twenty years. To be sure, Getz had led a turbulent life of drug addiction and jail sentences. I remember reading an apology of his behavior by Getz in a Downbeat issue of the late 1950’s, which is decent or odd, depending on your view or mood. Contrary to general opinion, the withdrawal symptoms of cold turkey are not horrible or a hellish hurdle. Nasty, for sure. But the thing is, it’s harder to stay clean and Getz struggled all his life. Not least during his second marriage with Swedish Monica, who was his manager for many years. Quite the task. Getz was a tough customer. Few if any colleagues sang praise of his personality or were liable to break into my buddy your buddy misses you… On the contrary. When Getz had heart surgery later in life, trombonist Bob Brookmeyer commented: “Did they put one in?” Ouch.

Let there be no mistake that in the first place though, Getz was a gorgeous tenor saxophonist who released top-notch records as early as the early 1950’s on Norman Granz’s Norgran label and became the incredibly successful frontman of the bossa nova craze in the early 1960’s. What are your favorite Getz albums? Mine? Sweet Rain (1967) is something else. I think Live At Storyville 1 & 2 (1951) with Jimmy Raney is indispensable. Classic stuff. His ‘with strings’ album Focus is intriguing and groundbreaking. I’m crazy about The Steamer. (1956) But I’m even more crazy about Dynasty. Not only underrated and essential Getz, but a masterpiece of organ jazz as well.

The early summer of 1970 found Getz in Paris, where he visited the tennis tournament of Roland Garros. Why not? A bit of relaxation won’t hurt. Getz may have seen Czechoslovakian Jan Kodes beat Yugoslavian Zeljko Franulovic in the finals. Remember? Nope. There is no doubt that these cats hit a mean ball, otherwise they wouldn’t have come this far. But their match could hardly have been comparable to John McEnroe-Björn Borg or Nadal-Djokovic. At any rate, while in Paris, Getz also went to the Blue Note club. There he saw the trio of French organist Eddy Louiss, Belgian guitarist René Thomas and French drummer Bernard Lubat. As Getz put it in the liner notes of Dynasty: “I had been told that jazz in France was dead, and sure enough the club was almost empty. I walked in and my mouth fell open. I heard some hard core swinging jazz, everybody was dipping in, really taking their piece.” Getz arranged a couple of unannounced rehearsal engagements at the Chat Qui Pêche. “I decided then and there to present these musicians to the rest of the world.”

And so it came to pass. That is, after a short while. Getz had to hurry back to the USA when his father passed away in the fall. Back in Europe, the band was recorded at Ronnie Scott’s in London in March, enough material to fill a double LP set, though it is said that a small part was recorded in the studio. It’s an enchanting, hypnotic release. Don’t we all have big favorites? Don’t we all share stories of records that we never tire of hearing and that have found a special place in our hearts? Usually, these are the kind of albums that we discovered in our youth, making an indelible impression, mingling with the confusing and liberating forces of adolescence… It’s a kind of magic. Later in life, we still cherish and listen to these favorites. We can dream them up in a flash. They take you back to the innocence of youth, the internalization of hurt… You with me? You play any big favorites?

Musicians are aficionados and listeners as well. And vice versa, occasionally. Musicians know all about magic. And the absence of it. They love to be in a zone and work a bit of magic, to approach that feeling of innocence and internalize hurt, feelings that are recognized by the audience. I think that some people at the three nights at Ronnie Scott’s from March 15-17 definitely were in a zone. To begin with, Stan, Eddy, René and Bernard. I think that the audience at Ronnie Scott’s was damn lucky. Getz is flying like an eagle, swift and flexible, eyes on its prey, swooping from the edge of a breeze, winner taking all… He’s sweet, a father caressing his son. His tone is velvet, candlelight, golden earrings on a Parisian brunette. He hasn’t been nicknamed The Sound for nothing.

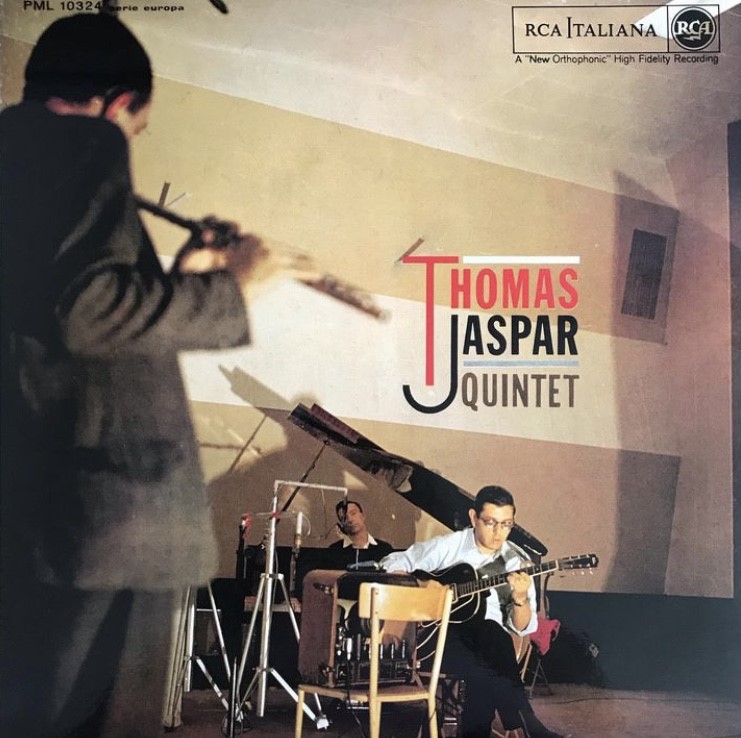

Getz was impressed by these European cats with good reason. Actually, René Thomas was relatively known in the United States. Getz may not have been familiar with him but the acclaimed guitarist from Liège in Belgium had made a big impression in New York and Montréal from 1958 till 1961. Collaborators Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins had expressed their admiration of Thomas. Thomas recorded one album for Riverside in the USA – Guitar Groove. It seems to me that Thomas is involved to no end, always playing as if his life is depending on it, always brimming with ideas. Then there’s the unmistakable gypsy-feeling of the legendary stylist from Wallonia, same area where Django Reinhardt was born and raised. And Toots Thielemans, from Les Marolles in Brussels. Lots of brilliant poets of sound out there.

Born on the island of Martinique and formerly a singer in the popular group Les Double-Six, Eddy Louiss was a pianist and organist that strayed from the Jimmy Smith-style and came into his own as a challenging player that crossed genres and peppered his lines with exotic twists and turns. His sounds veer towards the solid tones of Brian Auger and Keith Emerson. The band plays strong tunes by Louiss, one cooperation between Louiss and Thomas, two by René Thomas, one by Albert Mangelsdorf – Mona – and one standard by Bronislau Kaper – Invitation. The CD reissue includes Benny Golson’s I Remember Clifford.

None by Mr. Getz. Always the supreme interpreter, Getz delivers some of the finest tenor stories of his career… a snake charmer of the tantalizing Dum! Dum! Dum! and a Neo-Lestorian King of modal-bop-latin-funky-ish Our Kind Of Sabi, both highlights that feature classic Eddy Louiss… immaculate bass lines, subtle accompaniment, moving from satin cushion to church to brick wall sounds and swinging with swirling, chili pepper lines… the European answer to Larry Young. Getz stuck to his word. Plenty of room for ses amis to stretch out. Plenty of absolutely killer songs that are captivating from start to finish.

Dynasty is like waking up in the wee hours of the morning, drowsy, or as we say around here, sleepdrunk, realizing that you had the coolest dream, striving to return to it immediately, if only… Getz provides, Getz was in a zone. Did Jan Kodes found himself in a zone in his final match on Roland Garros? His zone perhaps, but not the zone. You have to ask Roger Federer for that kind of zone. How is it to be in that zone and how is it when it’s absent and is it something you can ignite? Who knows what the answer by Federer will be? What the answer of Getz would’ve been? Hard to tell. But we can take a wild guess.

Wild guessing also applies to the question why this band broke up. It is said that, when Getz wanted to take this European group to the USA, union disagreements put a stop to this. The other story though is that Getz had a beef with Lubat and wanted to add Roy Haynes to the group. Thomas and Louiss stood behind Lubat. More likely. End of a fantastic band.