Heavyweight sideman came of age as a leader in the late 1960’s.

Personnel

Harold Mabern (piano, electric piano), Blue Mitchell (trumpet), George Coleman (tenor saxophone), Bill Lee (bass), Hugh Walker (drums)

Recorded

on December 23, 1969 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR7624 in 1970

Track listing

Side A:

Rakin’ And Scrapin’

Such Is Life

Side B:

Aon

I Heard It Through The Grapevine

Valerie

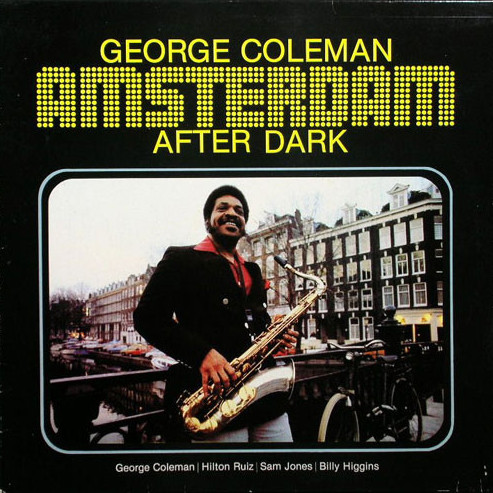

Harold Mabern was born in Memphis, Tennessee, major capital of rhythm and blues and soul, where young Harold, as he reminisces in the liner notes, asked his father for some money, his father with his very modest income replying that he’d try to rake and scrape up some. Hence the title Rakin’ And Scrapin’. Mabern grew up with buddies Booker Little, George Coleman and Frank Strozier. Mabern’s debut album as a leader was From Memphis To New York in 1968. Mabern moved to New York City in 1959 and stayed true to The Big Apple, a stalwart for exactly sixty years, till his passing in 2019 at the age of 83.

New York jazz is heavily indebted to Mabern, exceptional hard-bop and post-bop pianist that played and recorded with Lionel Hampton, J.J. Johnson, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley and Freddie Hubbard, who vigorously and enthusiastically passed on his knowledge to the new breed. Mabern was closely associated with Eric Alexander, Joe Farnsworth, Steve Davis and other contemporary class acts that came up in the early 1990’s. His last recorded efforts were Mabern Plays Coltrane featuring Alexander and Vincent Herring in 2018 and a feature on the late great drummer Jimmy Cobb’s last album This I Dig Of You in 2019. Warriors until the very end.

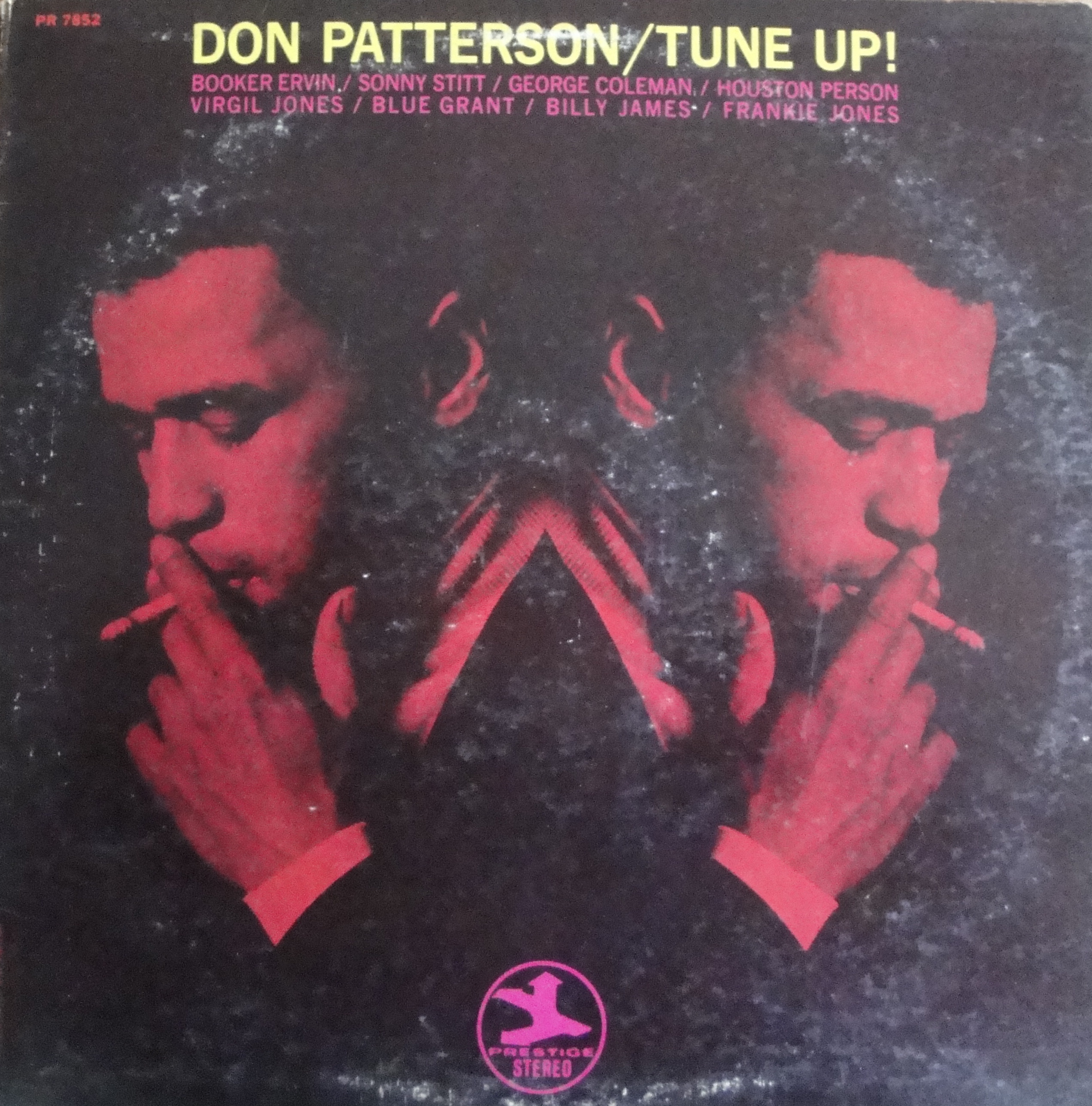

What you get in the aftermath of Lee Morgan’s surprising hit of The Sidewinder on Blue Note in 1964 is rival companies like Prestige that rely on the skills of their artists to write a promising, catchy tune, in this instance Harold Mabern’s Rakin’ And Scrapin’, lurid boogaloo affair that features vibrant solos from trumpeter Blue Mitchell and tenor saxophonist George Coleman, good company. Rakin’ And Scrapin’ wasn’t a big seller, it was 1969 ok, all across the USA, another year for me and you, another year with nothing to do, as Iggy Pop from The Stooges sang, though, actually, plenty was happenin’, chief among those the Vietnam War crisis, while interest in mainstream jazz dwindled and rock jazz was on the rise. Plenty of people enjoyed funky stuff, provided by musicians that jazzed up James Brown and The Isley Brothers. Competition for Mabern (Lou Donaldson, Lonnie Smith, Eddie Harris, Boogaloo Joe Jones) was fierce.

Who cares, it’s 2022, oh my and a boo-hoo, continuing sagas of crises, and we’re looking back on a charmingly quirky mix of music, which besides Mabern’s boogaloo tune veers between serious post-bop and the electric piano-driven cover of I Heard It Through The Grapevine, which, admittedly, is rather stiff and superficial. Contrary to this, Mabern’s uptempo Aon hits bull’s eye, a sparkling piece that extends the refreshing work of Herbie Hancock and Andrew Hill from the mid-1960’s and features intense piano stylings by Mabern. Torrents of notes, like bountiful drops of water from a fountain. Punchy and dense “McCoy Tyner” chords and voicing. Top-notch stuff.

Mabern’s Such Is Life is no joke either, the kind of original ballad that should be picked up by contemporary jazzers besides perennial favorites as Body And Soul and Darn That Dream. Just a thought.

Listen to the full album on YouTube here.