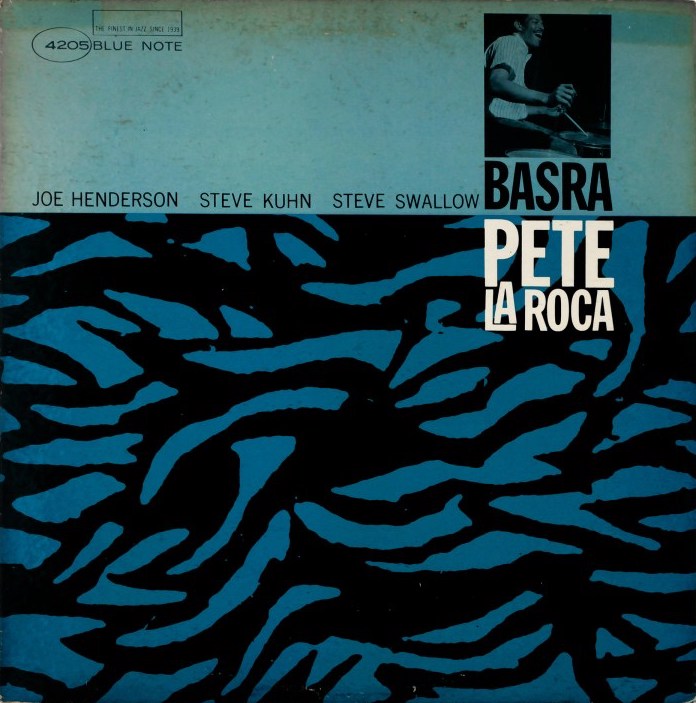

Drummer Pete La Roca delved into exotic modality on his much-admired 1965 record on Blue Note, Basra.

Personnel

Pete La Roca (drums), Joe Henderson (tenor saxophone), Steve Kuhn (piano), Steve Swallow (bass)

Recorded

on May 19, 1965 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as RLP 12-232 in 1956

Track listing

Side A:

Malaguena

Candu

Tears Come From Heaven

Side B:

Basra

Lazy Afternoon

Eiderdown

If I say Pete La Roca you will most likely answer with: Sonny Rollins, Live At The Village Vanguard. Small wonder, since it is his feature on Rollins’ game-changing LP that put him squarely in the vision of the night binoculars of serious jazz fans. Bird watchers may constitute a fanatical breed, blessed with encyclopedic knowledge, waiting patiently in their cabin in the woods. But serious jazz fans are a passionate lot as well. They spot a gem from miles away and will discuss the merit of the “birds” that play on the disc much in the manner of monks pondering over the words of Saint Augustine.

La Roca shared sideman duties on Village Vanguard with the developing genius of Elvin Jones. As the sole accompanist, however, there are plenty of top-notch features that serious jazz fans cough up effortlessy. He played on, for instance, George Russell’s cutting-edge The Outer View, Joe Henderson’s hard bop winner Page One, Jaki Byard’s far-out Hi-Fly, Slide Hampton’s soulful Sister Salvation and Art Farmer’s folk song gem To Sweden With Love.

La Roca recorded only three albums as a leader: Basra, Turkish Women At The Bath (Douglas 1967) and Swingtime (Blue Note 1997). La Roca – born Pete Sims, the pseudonym was made up after years of playing in Latin bands in his birthplace of New York City – was a taxi driver in the 70s. It’s a disgrace that fine black artists as La Roca had to resort to day (or night) jobs, however honorable the menial activity may be. But it must’ve been one swinging cab. La Roca subsequently attended law school at New York University and returned to jazz in 1979. He passed away in 2012 at age 74.

Basra and Turkish Women At The Bath are highly collectible artifacts, acclaimed albums for the wildly ecstatic ‘bird watchers’. With sound reason, it’s a hell of a couple of albums. Turkish Women is impressive experiment, terse complex groove and abstract painting, as much colored perhaps by Chick Corea than LaRoca, though, it must be said, La Roca wrote all originals. (It was released by Muse under Corea’s name as Bliss, which La Roca successfully fought in court) Basra is progressive mid-sixties Blue Note, on par with the records of Bobby Hutcherson, Herbie Hancock, Jackie McLean, adventurous with a keen sense of the past. It’s a sleeper for the general audience, a winner for the birdwatchers. And it features a number of interesting feathered creatures: tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, pianist Steve Kuhn and bassist Steve Swallow.

Both Malaguena and Basra are one-chord (Spanish and Eastern-flavored) drones resting on the fantastic, loose-but-solid drumming from La Roca. Either the man’s got a hip approach to the snare drum or his engineers were in continuous top form, but I’ve heard a lot a awesome drums sounds from La Roca. His snare drum is the Crisp of Crispiness, a healthy slap in the face, cocky like a 42nd Street hustler and wide like the open spaces of East Texas. Joe Henderson is comfortable with the exotic groove, his patiently timed clusters of grunts, growls and bellows on the drone admirable. Henderson whirls lines around the chord like the way a snake charmer directs the movement of the reptile on the streets of Manila or Punjab. He really creeps deep into the vessels of the groove. Candu is loose-jointed blues, Tears Come From Heaven a crisp modal romp, Eiderdown a dark-hued Wayne Shorter-ish melody, Lazy Afternoon a piece of slow-moving ambience with a leading role for the impressionistic Steve Kuhn.

Sometimes the rebellious La Roca hits his polyrhythm as hard and wide as Elvin. Can you imagine?! It’s that kind of excellence and power driving Basra, coupled with the Rudy van Gelder touch, that has for many years now caused the bird watchers to drop their binoculars in awe.