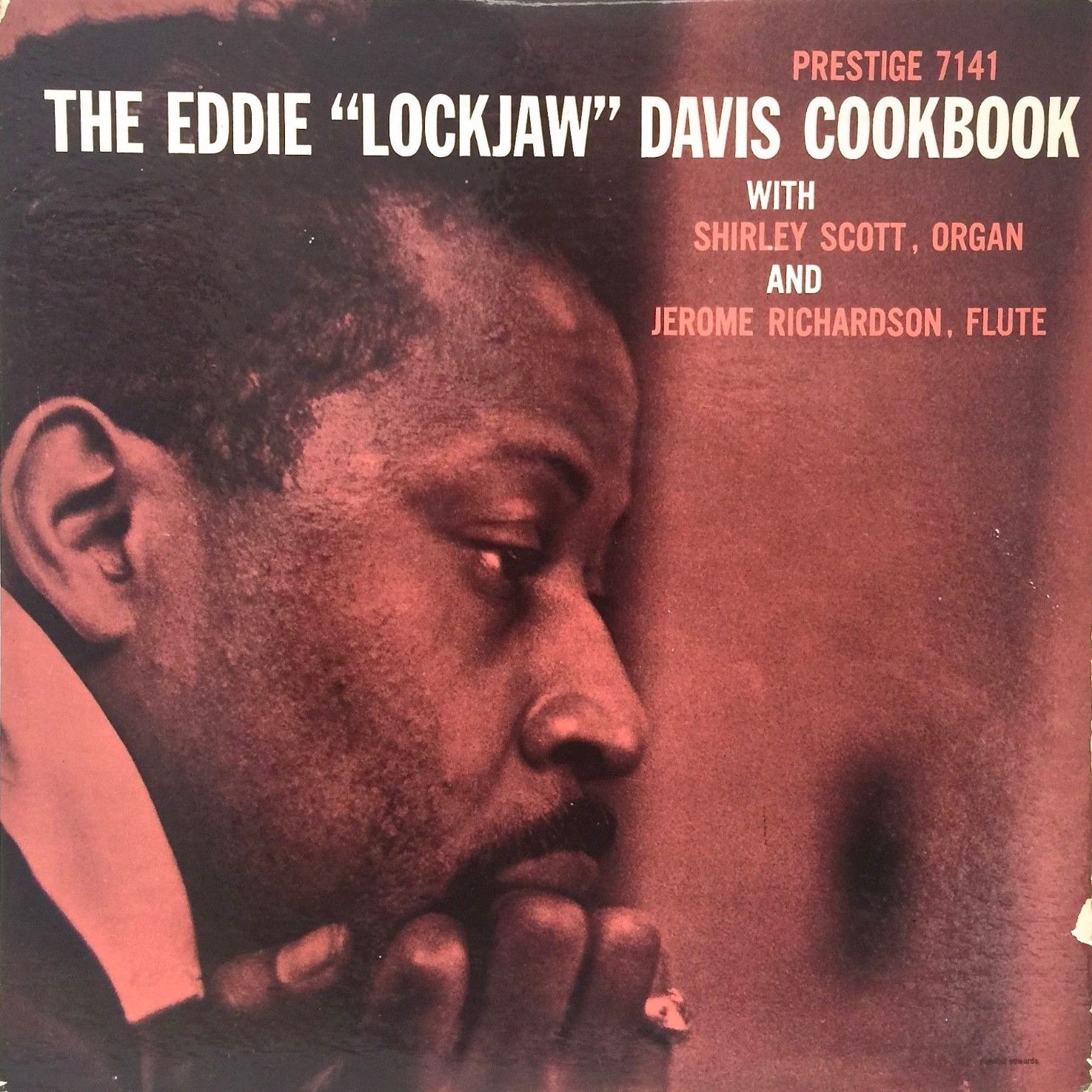

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and Shirley Scott pass the peas back and forth on their soul jazz hit album Cookbook.

Personnel

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis (tenor saxophone), Shirley Scott (organ), Jerome Richardson (flute A1-3, B1, B3, tenor saxophone B2), George Duvivier (bass), Arthur Edgehill (drums)

Recorded

on June 20, 1958 at Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as PRLP 7141 in 1958

Track listing

Side A:

Have Horn, Will Blow

The Chef

But Beautiful

Side B:

In The Kitchen

Three Deuces

Avalon

Before DJ and promoter Alan Freed coined the term ‘rhythm & blues’ in the advertisements for his groundbreaking package shows in 1947, rendering it commonplace almost immediately, ‘race’ music was the general term for black popular music. Most likely, black musicians like Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis weren’t very focused on labels as ‘race’, swing and r&b, as long as their efforts led to the required financial rewards to pay their bills and put bread on the table. Davis played with Cootie Williams, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie in the early forties (throughout his career, Davis would have extended stints with Basie) and churned out jump-and-jivin’ honk-fests for labels like Savoy and Apollo for the rest of the decade. Meanwhile, the ‘new’ jazz created by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke was labeled ‘bebop’. It is usually overlooked, but Davis mingled smoothly with the pioneering crew, functioning as MC on the bandstand of Minton’s Playhouse, not without adding his brand of tough tenorism, lest we forget. He also cooperated extensively with Sonny Stitt during the fifties.

In the mid-fifties, Davis recorded a number of albums with organist Shirley Scott on King, Roulette and Roost that were well-received by the small circle of admirers of the hard-working group on the ‘chitlin’ circuit’, the network of clubs in the nation’s black neighbourhoods. Few could foresee the succes of their subsequent recording on Prestige. The fact that Prestige, securing better distribution deals and more airplay, immediately re-issued Cookbook as Cookbook Vol.1 and subsequently also released Vol.2 and Vol.3 gives a good idea of the group’s popularity at that time. Their attraction, nonetheless, also faded fairly quickly and soon after Davis formed a more ‘hard bopping’ partnership with fellow combative tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin on the Riverside label from 1960 to 1962.

It is rather amazing, in hindsight, that a long slow blues like their take on Johnny Hodges’ In The Kitchen (12:53 minutes, although obviously, Jerome Richardson’s solo was deleted for the purpose of the length of a 7inch) turned out to be the group’s big jukebox hit. There’s no use getting trapped in the web of nostalgia and romanticizing. But one can easily imagine black folks tapping their feet and slightly shaking their hips while the sounds of In The Kitchen reverberate against the wall of a BBQ joint at the corner of 110th Street and Lexington Avenue. As Charles Bukowski wrote: Style is a way of doing, a way of being done. You might want to let this sink in while opening another bottle of Chateau de Catpiss.

It means that the Afro-American citizens of the post-war years possessed a hip musical taste. As people who’ve lived to tell occasionally have revealed, it wasn’t uncommon to comment among themselves on music of both Jackie Wilson and Ramsey Lewis, both Louis Jordan and Gene Ammons. Although soul jazz wasn’t complex jazz, it also wasn’t as ‘primitive’ as sometimes assumed. Moreover, it had a social function, as people shared their enthusiasm on nights out into town, eager for solid, funky entertainment. With the introduction of crack and the subsequent disintegration of the neighborhoods in the early seventies, the cohesive force of music received a big blow.

Shirley Scott’s solo on In The Kitchen seems filled with her memories of the sermons she attented in her youth. More like her forefathers Milt Buckner and Wild Bill Davis than modernist Jimmy Smith, Scott focuses on riffs and a theatre/accordion-type sound. Then it’s Lockjaw’s turn. Initially, Davis noodles age-old blues licks with a low-volume, breathy sound, but he progressively speaks up more forcefully and finally his howls take over the recording studio of Rudy van Gelder in Hackensack, New Jersey. One of the pleasures of playing with “Lockjaw” must’ve been that his imposing sound and scabrous style effectively pushes a group forward. Stimulated considerably, Jerome Richardson delivers a blues-drenched flute solo with a remarkable ‘singing’ tone and some rugged tongue-effects.

It may not be surprising, considering the regular working schedule of the Davis/Scott outfit at the time, that there are more tunes on Cookbook that are full of delicate interaction and rock-solid swing. The fast-paced Avalon runs smoothly, both “Lockjaw” and Richardson’s balladry of But Beautiful is tender as well as meaty and the three uptempo songs The Chef, Have Horn, Will Blow and Three Deuces (presumably titled after the club on ‘The Street’ – 52nd Street, NYC – and with a rousing feature of Jerome Richardson on tenor) are first-class potboilers. Davis unites the terse swing of Ben Webster and a bit of Webster’s vibrato with deceptively nonchalant phrasing, freely and playfully making use of slurs, barks and husky honks. His way of stringing together lines sometimes has a peculiar, otherwordly quality. Like someone is spinning backwards a sax solo on the turntable. At the same time, Lockjaw sounds as if he has to scrub the dirt of his shoes every time he returns home from a gig. Mutually stimulating contrasts, resulting in an unforgettable kind of sax poetry.