At the distinguished age of 73, pianist Rein de Graaff preserves a childlike enthousiasm for his trade, which he typifies matter-of-factly as ‘bebop, ballads and blues’. As a boy of 15, De Graaff entrusted his equally jazz-crazed pals with the wish to one day play with his heroes Hank Mobley, Dizzy Gillespie and Dexter Gordon. “I never would have thought that dream to come true. But, amazingly, it did.”

They told me De Graaff had long since decorated one of his rooms in his countryside bungalow as a jazz museum. Well, make it

two rooms. De Graaff has led me from one room, filled with the monumental archive of his career and hundreds of jazz magazines (e.g. all Downbeat Magazine issues up to 1970, which speaks for itself if you’ve learned to know anything about De Graaff’s tastes) to another that hosts a grand piano, walls adorned with vintage photographs, concert posters and a vast collection of original classic bebop and hardbop albums on labels as Blue Note, Prestige, Clef/Norgran, Savoy, Bethlehem and Argo. I’m the drooling kid in the candy store. Come to think of it, if it comes to collecting vinyl, Rein de Graaff transforms into a boy that has entered the Efteling amusement park as well. Collecting has been a lifelong passion. “I just got back from a Los Angeles festival. There was a record fair just outside the Capitol building. It was great!”

For De Graaff, the classic jazz of the late fourties to the late sixties that his speaker system churns out has always remained the real deal. “Jazz shouldn’t be too clean, it has to have an edge, something dirty and smoky. The music I play comes from the smoke-filled clubs, where sex often was cheap, and the blues was heard… I started out at the end of the era when New York clubs had music from 10 to 4. And then there was Slugs’. I usually went to bed at 8 in the morning. Nowadays, I’m having breakfast at 8! Naturally, there was something going on. I mean, who’s sitting at the bar? Hustlers, for instance. It was partly a criminal environment. All these things somehow ring through in the music.“

No reason for Sam Spade to stake out De Graaff’s Veendam residence, though. Just the music. A gentlemen from peat country, the north-eastern region of Groningen in The Netherlands. A man for whom a bargain is a bargain. This man has been a boy, frail and white as whipping cream, who happened to land in classic jazz paradise. That, indeed, is Rein de Graaff’s unusual, arresting story.

Partly anyway. It was clear from the outset that the young man from an upper middle-class family had a natural talent for music and playing piano that could bring him places. The boy had soaked up the sounds of Charlie Barnett, Winifred Atwell and played ragtime when one day the radio broadcasted Charlie Parker’s Shaw ‘Nuff and Stupendous. He heard Bud Powell play Tempus Fugue-It, Clifford Brown blast through All Chillun Got Rhythm. The kid was hooked, caught in ‘Webb City’. Getting involved into bebop with a cultish zeal reminiscent of its inventors, Rein de Graaff’s self-taught playing matured, under further influence of albums as Interpretations By The Stan Getz Quintet, The Jazz Messengers At The Cafe Bohemia and Griffin/Coltrane/Mobley’s A Blowing Session.

“People usually stay true to the music that makes an impression on them when they’re 15 or 16. It’s ingrained. That certainly holds true for me. Introducing Lee Morgan was and still is an all-time favorite. Hank Mobley is stunning, and the rhythm section is extremely lively. Of course, Blakey backed Mobley on some wonderful classics, like Soul Station, but the Art Taylor/Doug Watkins combi is dear to me.”

“I have most of the classic West Coast albums now, but I didn’t like West Coast jazz when I was young. The only record I liked was Shorty Rogers’ Modern Sounds. Take a listen here, that’s not cool, right, it’s hot! Great arrangements too. A bebop album that blew my mind was It’s Time For Dave Pike. Yeah man, that’s great, it’s Charlie Parker on vibes. I took it to his gig at a club in Groningen in 1967 and asked Dave Pike to sign it. I wasn’t a kid anymore but thought to give it one more go as far as signatures were concerned! I felt that our thought processes were alike. And it proved they were. Later on, when we became friends, it totally clicked. By the way, that vibraphone over there is the one that Dave used for the It’s Time For Dave Pike album.”

(From left, clockwise: Lee Morgan – Introducing Lee Morgan, Savoy 1956; Shorty Rogers – Modern Sounds, Capitol 1952; Dave Pike – It’s Time For Dave Pike, Riverside 1961)

By the early sixties, De Graaff, who didn’t fancy getting into Chopin and the like at Conservatory, gigged steadily, had won a prize at the Loosdrecht Jazz Festival, toured Germany with a swing orchestra, and even shared the stage with Sonny Stitt at the Blue Note in Paris. Back in The Netherlands, De Graaff scoured Amsterdam clubs, particularly the Sheherezade, where the expatriate tenor saxophonist Don Byas mentored young lions like De Graaff and his friends and colleagues such as saxophonist Dick Vennik, drummers Eric Ineke and John Engels and trumpeter Nedley Elstak.

But the big year for De Graaff turned out to be 1967. The pianist rises from his chair and beckons me to come up close to the photo wall. “So you’ve seen the big picture of me and Hank Mobley on stage over there, right. But look here, this one you have never seen. Hank, Evelyn Blakey (Art Blakey’s daughter) and me, we’re watching tv.”

In 1967 the 24-year old De Graaff traveled to New York. He said to his friends that he wanted to experience the jazz life of his heroes and, jokingly, added that his main goal was to play with Hank Mobley. For De Graaff, Hank Mobley was and has always remained the personification of jazz. “I got out of the subway in the Lower East Side and the first man I saw was walking with a trumpet case at the other end of the sidewalk. He looked familiar. He looked like Kenny Dorham, one of my all-time heroes. I followed him for a while and then had collected enough nerve to ask if he really was Kenny Dorham. Indeed he was! Subsequently, Dorham invited me to come up to the East Village Inn at night.” The following week, De Graaff hung out with musicians like Walter Davis Jr., Barry Harris and Evelyn Blakey, at whose place De Graaff had dinner one night. Evelyn knew of Rein’s wish to see Mobley and invited Mobley as a surprise guest for the astonished, skinny piano player from Holland. “She asked me to open the door. I obeyed. My heart burst out of my chest. There was Hank Mobley. ‘Hi, I’m Hank’, he said.”

In New York, De Graaff played with Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Elvin Jones and Joe Farrell. It was a dream come true. It was pretty devastating, however, regardless of their brilliant, swinging game, to see his heroes play sleazy bars for a nickle, while he opinioned that their stature should be of concert hall level, and to see some of them, like bassist Paul Chambers, succumb to a dreary, destructive alcoholic life style. “I saw some of that as well in Germany and The Sheherazade, it was a bit scary. I decided to follow a different path.”

The following decades would see the pianist lead a prolific but most unusual jazz life. Working by day in the electro ware wholesale company of his father (which De Graaff continued in later life and sold at the age of 56), De Graaff played at night and during days or weeks off. His popular De Graaff/Vennik quartet ventured more and more into modal jazz territories, while De Graaff also supported Americans such as Johnny Griffin, Dexter Gordon, Clark Terry, Arnett Cobb, Dizzy Reece, Carmell Jones and Red Rodney on their Dutch and European gigs. Great experiences, with lessons to be learned as well, like those from Griffin and Art Taylor, who played either at furious breakneck speed or extra slowly, getting into a distinctive ‘groove’, something De Graaff called ‘American Tempos’.

It was an outrageously busy lifestyle. Better to burn out than to fade away? “I didn’t drink. That helps. And I was young, able to get along without much sleep. Sometimes I got home at 4 in the morning and was at the office at 8! And for instance, when I had a business meeting far away, I would combine it with a gig the night before! Most of all, playing jazz was my high, gave me a lot of adrenaline. My work gave me a kick as well. All that keeps you on your toes!”

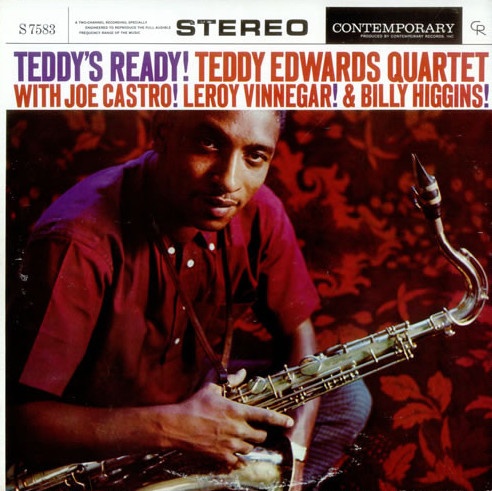

De Graaff’s skin has that antique porcelain quality. Aged but still quite smooth. Strands of yellow-ish hair embellish a white crop, like sheep wool. Slightly wavy hair, and always that broad curl at the back of his neck. Not too neatly trimmed. An edge. “But yes, I lived three lives. My wife and children are proficient in music and they were understanding.” Then, dryly: “I wouldn’t have married her otherwise. But indeed, I was away a lot and didn’t see enough of my little daughter. I decided to do it differently when my son was born. The kids loved it as well, though, having those Americans around. Instead of hotels, they stayed at our place. Teddy Edwards and Babs Gonzalez were housefriends. Babs always played checkers with my kid daughter,” laughs De Graaff. More laughs erupt when De Graaff recounts the extended sleepovers of Johnny Griffin and Art Taylor, who always slept in a bunk, ‘can you imagine?!’

A white boy amidst Afro-American legends, many of whom were desperate, troubled, grappling with racism, dissapointed in American society, and, like Art Taylor, quite militant about it. “You’ve read Taylor’s book Notes and Tones, right? (Ed., Art Taylor’s controversial 1982 book of interviews with fellow musicians) The thing is, these guys transformed into Europeans in a way. Don Byas spoke Dutch, Art Taylor spoke French. Life in Europe wasn’t so stressed, they were more relaxed in general. In The States, the cops were on their backs all the time and they were ripped off regularly. It wasn’t like that over here.”

“Musically, I just gave my best. At the start of my career in New York, and later in Detroit with trumpeter Louis Smith, I was sometimes the only white musician in the group. Oh, I’ve had a bassist say to me once, (De Graaff puts on a deep, gritty voice) ‘Show me how good you are’. I made sure I did. The thing is, jazz is the shared language. You communicate on that level. I remember what the emcee said when I was on stage with Hank Mobley. He said: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, how about a big hand for Hank Mobley, Herbie Lewis and Billy Higgins, and the young man from Europe. You heard the man, he’s preaching the same message as we do.’”

(From left, clockwise: Dexter Gordon & Rein de Graaff; Rein de Graaff, Herbie Lewis, Hank Mobley & Billy Higgins; Art Taylor, Henk Haverhoek, Johnny Griffin & Rein de Graaff)

I mention De Graaff’s version of Gil Fuller’s I Waited For You (from Drifting On A Reed, Timeless, 1977), a classic De Graaff cut of long, flowing lines, spare blue notes, tumbling and rollicking lyrical modes and some ‘out’ phrases. “That was inspired by Joachim Kuhn, who although he didn’t really swing, was outrageously good. I was into McCoy Tyner as well, our quartet developed more of a ‘new thing’. Musicians advised me to quit bebop, start something new. It was kind of a breather for me, a liberation, really. And the quartet was so propulsive! That avantgarde stuff didn’t sit too well with the legends, though. I remember Dexter Gordon saying one night, ‘Rein, stop that Chick Corea shit, will you!’

The quartet existed until 1989, but in the late seventies De Graaff again took some advise to heart. “Now audiences said, ‘Hey Rein, you used to play such beautiful bebop, why don’t you get back into that? Of course that’s when I went to New York to record New York Jazz (Timeless/Muse, 1979) with Tom Harrell, Ronnie Cuber and the classic rhythm section Sam Jones and Louis Hayes. I used to play along with all those Cannonball Adderley albums at home, you know!”

A combination of Horace Silver, Bud Powell, Sonny Clark, Hampton Hawes and a touch of Lennie Tristano, De Graaff has made his mark as one of the premier European bebop/hardbop pianists. An ‘unpianistic’ pianist, relishing long, flowing lines that he tries to construct as horn men do. A more gentle touch, like his friend Barry Harris, in contrast to Powell’s hammering lightning bolts. “Someone in The States once said to me, ‘hey man, you blow a nice piano!’ Horns have fringes. Playing piano like Oscar Peterson is not my ambition. He was the best in the world, but I couldn’t care less. All over the keyboard, flurries of arpeggio’s, brilliant, perfect playing, but constant brilliance and perfection becomes boring after a while.”

“I think I was a fanatic. That’s crucial, you gotta have that dedication and obsession. Let me tell you a story guitarist Peter Leitch told me. He teached a class at Conservatory, there was a talented guitar player. Leitch said, ‘okay, I’ll see you at the workshop on Friday.’ The young man said, ‘No, I can’t make it, I have to hang wallpaper at my grandma’s’. You know, that’s not the right mentality. Small wonder, we’ve never heard from the gentlemen since.”

Like Barry Harris, De Graaff has been a true ambassador for bebop and hardbop. From 1986 till his 70th birthday in 2012, De Graaff gave four lecture/tours a year, playing and explaining the music that grew out of Charlie Parker et al. Essential jazz history, embellished by an endless list of acclaimed and underrated Americans: Teddy Edwards, Clifford Jordan, Johnny Griffin, James Moody, Ronnie Cuber, Charles McPherson, Harold Land, Houston Person, Frank Foster, David “Fathead” Newman, James Clay, Barry Harris, Webster Young, Bud Shank, Billy Root, Herb Geller, Al Cohn, Louis Smith, Art Farmer, Eddie Daniels, Lew Tabakin, James Spaulding, Bob Cooper, Gary Foster, Pete Christlieb, Gary Smulyan… That’s when people started nicknaming De Graaff ‘Professor Bop’. “That was the source. Guys like Johnny Griffin, he could tell how it was to play with Monk, Harold Land what Clifford Brown was about. And Teddy Edwards, come on, he invented bebop!”

Fortune’s favorite? A fullfilled man, certainly. But where have all the flowers gone? At 73, De Graaff concedes that he’s starting to become a regular visitor of the crematorium. De Graaff puts his arm in the air and moves a closed hand back and forth slowly. “It’s the Big Hand working. Here it goes, ‘swoosh’, takes a bunch of us, draws back again, only to resume its relentless work… Dave Pike passed away last year.” You can hear a pin drop. Says De Graaff, his face now a brittle mask that hides sorrow. Only human: “That really made me kind of sad. We were like bloodbrothers. But ok, we performed, made a record. Fine. At least, that’s consigned to posterity.”

“I’ve got nothing but nice memories. My favorites? The first time that I played with Hank Mobley is really dear to me. Also, my tour with Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt and Philly Joe Jones was fantastic. I knew these guys inside out from their records, but to sit beside them on stage really is something else. They play familiar phrases and licks, but the licks are theirs, original. The impact is enormous.”

His blue-grey eyes, mostly hidden behind wrinkled eyelids like ladybugs in the cracks of cobblestones, suddenly grow: clarity, earthiness, a little tenderness. “I carefully pick my recording projects, it has to be something fresh. That’s why I did duet albums and performed with two baritones, for instance. It’s still possible to be creative in bebop and hardbop, or what you’d call mainstream jazz. I will be doing my Chasin’ The Bird tour in the near future. That would give you an idea of what that tour is about, right?”

Rein de Graaff

Pianist Rein de Graaff (Groningen, 1942) recorded more than 40 albums, both as a leader and in cooperation with numerous Americans and fellow Europeans. He won the Boy Edgar Prijs in 1980 and the Bird Award at North Sea Jazz Festival in 1986. From 1986 to 2012, De Graaff organised Stoomcursus and Vervolgcursus Bebop: lectures about bebop, which included performances by a host of American and Dutch luminaries, as well as upcoming youngsters. De Graaff’s career is chronicled in Coen de Jonge’s Belevenissen In Bebop. (Passage, 1997)

Selected discography:

Body And Soul (with J.R. Monterose, Munich 1970)

The Jamfs Are Coming (with Johnny Griffin & Art Taylor, Timeless/Muse 1975)

Modal Soul (Timeless 1977)

New York Jazz (Timeless/Muse 1979)

Good Gravy (with Teddy Edwards, Timeless 1981)

Live (with Arnett Cobb, Timeless 1982)

Rifftide (with Al Cohn, Timeless 1987)

Blue Bird (with Dave Pike & Charles McPherson, Timeless 1988)

Nostalgia (Timeless 1991)

Blue Beans & Greens (with David “Fathead” Newman & Marcel Ivery, Timeless 1991)

Baritone Explosion (with Ronnie Cuber & Nick Brignola, Timeless 1994)

Alone Together (with Bud Shank, Timeless 2000)

Blue Lights The Music Of Gigi Cryce (Timeless 2005)

Indian Summer (with Sam Most, Timeless 2012)

Fried Bananas, the vinyl release of a 1972 Dexter Gordon performance with the Rein de Graaff Trio by Gearbox Records is due in November.