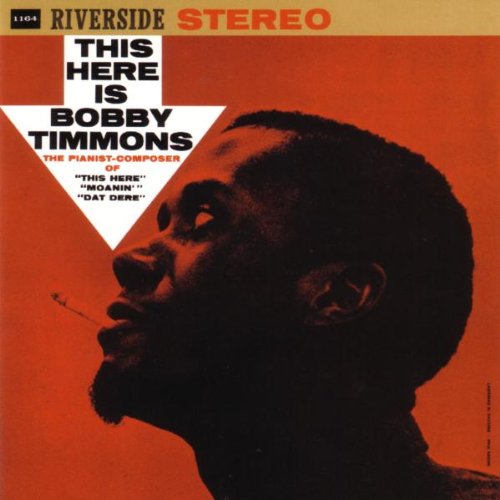

A working day that sucks the soul out of me. An argument with the woman that hangs suspended in the air like a radioactive snowflake on the leaf of a tree. Many of you know the drill. Or don’t. Me and my wife, we’ll catch up. But for the moment, what better cure than a good piece of music? Bobby Timmons’ classic cut This Here certainly qualifies. Lasting a mere 3:31 minutes, its forceful, gospel-driven beat and style is enough for at least a temporary driving out of demons. It comes upon me like a strong but gentle wave. I jump for joy. Am moved by its groove and feeling.

Personnel

Bobby Timmons (piano), Sam Jones (bass), Jimmy Cobb (drums)

Recorded

on January 13 & 14 at Reeves Sound Studio, NYC

Released

as RLP 1164 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

This Here

Moanin’

Lush Life

The Party’s Over

Prelude To A Kiss

Side B:

Dat Dere

My Funny Valentine

Prelude To A Kiss

Joy Ride

Cannonball Adderley used to introduce the tune, that became part of his set when Timmons joined his quintet in 1959, as ‘simultaneously a shout and a chant.’ Jazz waltzes often have a lithe, airy quality. Not This Here. It has relentless drive. Indeed, all tunes on Timmons’ solo debut on Riverside, This Here Is Bobby Timmons, swing from start to finish. Even ballads like My Funny Valentine. At the time, Timmons’ version of the tune, as Orrin Keepnews reveals in the liner notes of the album, was commonly referred to by Timmons’ colleagues as My Funky Valentine. Obviously, Timmons put a lot of church influence in his music. Timmons was raised in church, played church organ and his father was a minister.

Timmons had been part of major groups like those of Chet Baker, Sonny Stitt and Art Blakey, with whom he recorded his signature tune, Moanin’ in 1958. By the fall of 1959 Timmons had become part of the Cannonball Adderley Quintet. Their live album The Cannonball Adderley Quintet In San Francisco, recorded on October 18 & 20, 1959, was a smash (jazz) hit, largely due to their exciting rendition of This Here. Three months later, on January 13 and 14, Timmons recorded his first solo album with fellow Adderley member, bassist Sam Jones and drummer Jimmy Cobb. Cobb had been an Adderley member at various recordings from Winter 1957 to Spring 1959. By January 1960 Timmons had decided to return to Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. He would record Dat Dere with Blakey on March 6, 1960.

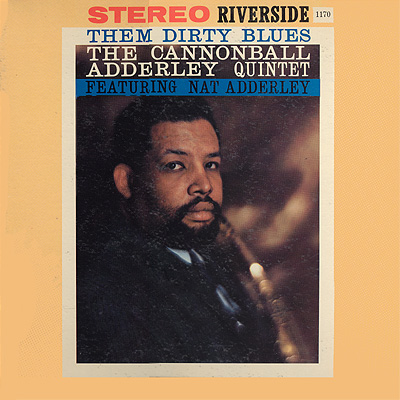

Dat Dere is longer than its ‘churchy’ cousin This Here, but the fire cracks almost as hard. Yet its playful, rollicking theme also has a moody quality. After Timmons states the theme in rootsy, Ray Charles-like fashion, the groove gets going. Then follows a Sam Jones intermezzo, whereafter the tune builds to a climax with a terrific shout chorus and a clever modulation that leads back to the theme. Timmons’ version has a rawer quality than ‘Blakey’s’ equally immaculate version. That version boasts Blakey’s inspiring accompaniment and great solo’s by Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter. In ‘Cannonball Adderley’s’ version on Them Dirty Blues of February 1, 1960, Timmons jumps into locked four-hands playing almost immediately. It’s a great solo but different.

‘Art Blakey’s’ iconic version of Moanin’ is as powerful as it can get. Timmons’ take isn’t short on hi-voltage energy either. Sam Jones’ deep sound and strong beat and Jimmy Cobb’s uplifting style coupled with Timmons’ tough yet playful left hand create an unmistakably groovy piece of hard bop. The piano sound of Timmons – robust, slightly feeble – ignites the atmosphere of a juke joint. The whole album benefits from this atmosphere. Intricate jazz loaded with feeling and a barrelhouse sound. It’s too good to miss.

This Here, Dat Dere and Moanin’ are iconic hard bop cuts that refreshed the jazz world of the late fifties and early sixties and inspired many generations of mainstream jazz musicians thereafter. One thing they have in common is that they never wear me out. Should we consider Joy Ride a fourth classic of Timmons’ Riverside album? Not a bad idea. It’s a piece of blistering bebop soul. Jimmy Cobb opens the uptempo tune with a series of cocky firecrackers and Timmons’ solo is a spirited mix of blues, Art Tatum and Bud Powell.

The tender Prelude To A Kiss shows the delicate side of Timmons’ personality. Lush Life’s dramatic flourish is enticing. Yet even in these tunes Timmons sneaks in bold, accurate blues lines. They make complete Timmons’ quintessential album This Here Is Bobby Timmons: a gospel-tinged, extremely swinging and articulate affair that’s imbued with a joyful sense of discovery. It kills me time and again.