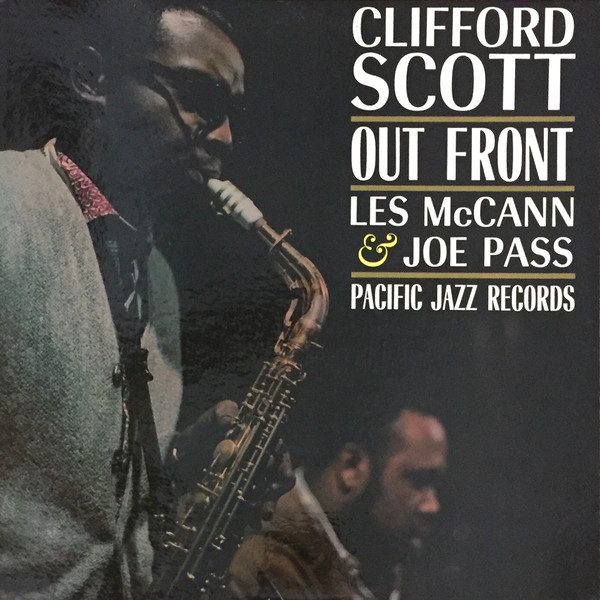

Check out this readily ignored but seriously hip and crafty piece of soul jazz and hard bop: tenor saxophonist Clifford Scott’s Out Front.

Personnel

Clifford Scott (tenor and alto saxophone), Joe Pass (guitar), Les McCann (piano), Herbie Lewis (bass), Paul Humphrey (drums)

Recorded

in 1963 at Pacific Jazz Studio in Los Angeles, California

Released

as PJ-66 in 1963

Track listing

Side A:

Samba De Bamba

Over And Over

As Rosie And Ellen Dance

Crosstalk

Side B:

Why Don’t You Do Right

Just Tomorrow

Out Front

As rhythm and blues developed into the most popular black music in the late forties and early fifties, a lot of jazz-oriented musicians jumped the bandwagon in order to make a decent living. Perhaps decent isn’t the appropriate term. Regularly, players switched from swing bands to r&b outfits, which usually meant a change from one grueling touring schedule to another. One bows in awe to them in hindsight, the way guys like Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, Red Holloway, Don Wilkerson or Sam “The Man” Taylor, survived. Tenor saxophonist Clifford Scott, born in San Antonio, Texas in 1928, deceased in 1993, traveled a similar route.

Scott worked with Amos Milburn, Jay McShann, Lionel Hampton, Roy Brown and Roy Milton in the early fifties. Scott provided the groundbreaking honking tenor solo on organist Bill Doggett’s jukebox hit in 1955, Honky Tonk. He stayed with Doggett for a number of years. Subsequently, Scott acted as a leader, trying to capitalize on the honking hype with singles bearing gimmicky titles like Bushy Tail and The Kangaroo, and recorded as a prominent session musician in the r&b and pop field. His last big stint, before settling down as a local hero in San Antonio, was with the Ray Charles band, intermittently, from 1966 to 1970.

Based on the West Coast in the sixties, Scott was featured on a number of Pacific Jazz albums by the organ combo Billy Larkin & The Delegates. Scott recorded Plays The Big Ones on Pacific Jazz in 1963, a gritty soul jazz date featuring Hammond organ. It’s a nice enough date but incomparable with Scott’s subsequent album, Out Front!. During that session, Scott expanded his scope, holding on to the fried-bacon notes and the occasional crowd-pleasing climaxes, while displaying distinct suppleness and double-time fluency. Coming with the slightest vibrato, Scott’s style is sensual as hell, and hot as hell as well.

Sensual also applies to the Les McCann Trio, which consists of McCann, bassist Herbie Lewis, drummer Paul Humphrey, plus Joe Pass, as in: attractive, uplifting, rousing. McCann had cooperated with Joe Pass on Richard “Groove” Holmes’ Something Special, Les McCann’s Featuring Joe Pass, On Time and Soul Hits. The gospel-drenched vigor and probing accompaniment of McCann, the group’s abundant swing and the subtle and peppery phrases of Pass provide a stimulating canvas for the lurid, lean strokes of Scott, whom one imagines must’ve been elated with the possibility of working with such an immaculate quartet.

And as is usual with the presence of McCann on a recording date, the pianist contributes a couple of catchy tunes, like the driving Out Front and the crisp stop-time cooker Over And Over, which is marked by the typical McCann device of a shift in key. McCann also wrote Crosstalk, killer greasy tune that is pure Bo Diddley’s Not Fade Away, thriving on the rousing beat and statements of McCann and Pass and the rubato wail of Scott that takes one by surprise like a tornado in New Mexico: a soul jazz gem stopping at a mere 2.45 minutes.

Samba De Bamba is a different ball game, an equally swinging, Latin hard bop tune. Developing his story from sophisticated, fluent phrasing to the kind of terse blowing of Ben Webster, Scott reveals himself as a singular stylist. This, perhaps, comes as no surprise considering his past in the swing era. It is surprising, though, that the saxophonist wasn’t granted the opportunity to record more extensively throughout his career, except for a couple of albums in the early 90’s. More than that, it is a shame.

Listen to the full album here.