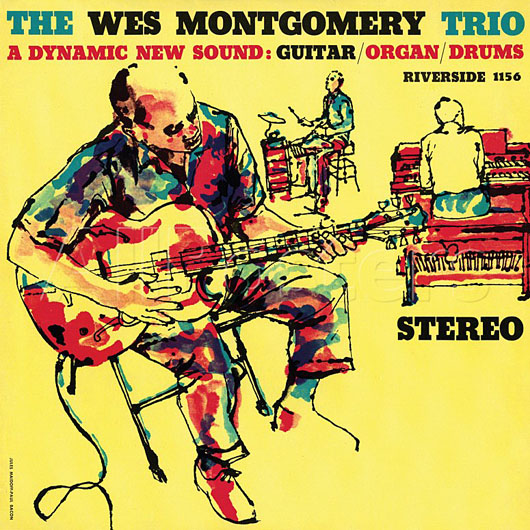

Adding ‘Style’ to Wes Montgomery’s debut album on Riverside, The Wes Montgomery Trio: A Dynamic New Sound, is more to the point. It constitutes the arrival of a guitar giant.

Personnel

Wes Montgomery (guitar), Melvin Rhyne (organ), Paul Parker (drums)

Recorded

on October 5 & 6 at Reeves Sound Studio, NYC

Released

as Riverside 1156 in 1959

Track listing

Side A:

‘Round Midnight

Yesterdays

The End Of A Love Affair

Whisper Not

Ecaroh

Side B:

Satin Doll

Missile Blues

Too Late Now

Jingles

Of this album, All Music says:

‘The only drawback is that the accompaniment, which though solid, doesn’t seem to perfectly match his guitar style… Montgomery’s performance was a revolution in technique and execution.’

That about sums it up. For readers of All Music and Ladies Home Journal. Nobody’s perfect and there must be more to the event of Montgomery’s marvelous recording debut on Riverside, released in the watershed year of 1959, which saw the release of three Ornette Coleman albums, Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue and John Coltrane’s Giant Steps. Coincidentally, Wes Montgomery declined an offer from John Coltrane to join his group. Instead, he built on the promise The Wes Montgomery Trio held, securing a spot on the scene through his Riverside recordings as the greatest jazz guitar innovator since Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian, a promise that was underlined first and foremost by Montgomery’s supple synthesis of single note lines, octave playing and block chords, effectively blown into studio and jazz club air by his distinctive, is-that-a-country-blues-picker’s?-thumb-touch, but certainly also by the subtle interaction of his group of childhood pals from Indianapolis, consisting of organist Melvin Rhyne and drummer Paul Parker, who’d grown into a tight-knit, mutually responsive outfit.

In his twenties, Montgomery landed a job with Lionel Hampton when the famed bandleader heard him copying Charlie Christian solo’s note by note, performed with his brothers Buddy and Monk regularly as the Montgomery Brothers and was featured on Kismet on Pacific, the LP of his brothers’ outfit The Mastersounds. Montgomery was noticed by a tongue-tied Cannonball Adderley in a Indy club, who introduced him to Riverside’s Orrin Keepnews, leading to a breakthrough at the ripe age of 36. The word that fits the impact of Wes Montgomery is: spellbound. Come on, from the moment Montgomery starts Monk’s ‘Round Midnight, the audience is melting, unable to resist the lure of Montgomery’s tasteful tale. In the confident hands of Wes, the micro-fragment of total silence marking the middle of Monk’s classic melody appears to be born for exactly that spot. The use of space, his timing, coming across especially enticing in his wonderful treatments of ballads, is one of Montgomery’s greatest talents.

In this sense, Rhyne is a perfect match to Montgomery’s classy style. His clear, logically developing lines and ‘plucky’ sound grace the bouncy, uptempo stop-time melody of the Montgomery composition Jingles, a swinging trio rendition. And to reciprocate Rhyne’s favor of charming, responsive backing, Montgomery smoothly accompanies the organist’s solo in The End Of A Love Affair, flowing from chord to chord like a pike-perch through the river weeds. The group’s take on Horace Silver’s Ecaroh is less spectacular, a medium-tempo groove that somehow doesn’t really gets into the groove, with, nonetheless, concise, excellent soloing.

Montgomery would reach the zenith of his recording career with the support of world-class guys like Johnny Griffin, Louis Hayes, Sam Jones, Wynton Kelly, Tommy Flanagan, Milt Jackson (Bags Meets Wes – wow – Full House – WOW) yet the total sum of The Montgomery Trio spells swing as well. At the core’s the style and sound of Montgomery, with a bite all his own. A fiery personality would be the incorrect way to describe Wes Montgomery- ringing through the articulate phrases is a man that didn’t want to be a nuisance to his neighbours, so he stopped playing with a plectrum and changed to the softer approach of his thumb – more apt is the assumption that the sparks fly (and they do fly high) almost solely on the strength of Montgomery’s dazzling brilliance and conception. His conviction, authority, is imposing. So much so that, once the driving Missile Blues, named after the club in Indianapolis, and the album is over, a new spin in order to fully enjoy and grasp the mastery of Wes Montgomery seems the best option to spend the next hour of the evening.