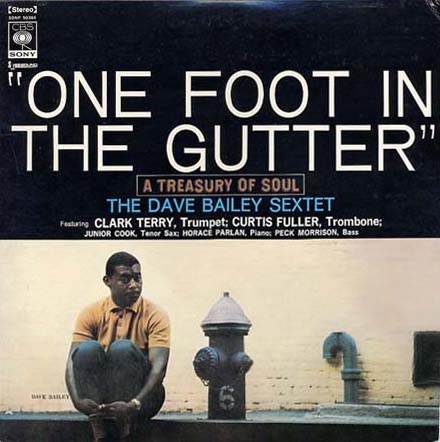

Solid, swinging drumming and great line-ups marked the albums drummer Dave Bailey made as a leader in 1960-61: a sudden burst of activity set off by One Foot In The Gutter.

Personnel

Dave Bailey (drums), Clark Terry (trumpet), Junior Cook (tenor saxophone), Curtis Fuller (trombone), Horace Parlan (piano), Peck Morrison (bass)

Recorded

on July 19 & 20, 1960

Released

as Epic LA 16008 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

One Foot In The Gutter

Well, You Needn’t

Side B:

Sandu

Cogniscenti and colleagues were in for a surprise when Dave Bailey quit the jazz life to become a flight instructor from 1969 to ’74. He somewhat returned to the scene when he picked up educational work for Jazzmobile in New York City after his stint on the airport. However, Bailey is remembered most of all as a top-rate drummer of the hard bop period, present on plenty fine albums from Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Stan Getz, Grant Green and Jimmy Smith. Three long-time associations stand out: Gerry Mulligan (1955-66), Lou Donaldson (1957-61) and Clark Terry (1962-67).

In 1960/61, Bailey recorded five albums as a leader for Epic, Jazztime and Jazzline with a number of illustrious contemporaries as Clark Terry, Kenny Dorham, Tommy Flanagan and Grant Green. Inevitably, some of those LP’s were re-issued under the names of his better-known colleagues. Reaching Out! was repackaged as Grant Green’s Green Blues, Bash! as Kenny Dorham’s Osmosis. One Foot In The Gutter met no such fate, regardless of Clark Terry, the obvious choice for companies eager to cash in.

Perhaps inspired by the success of The Cannonball Adderley Quintet’s Live In San Francisco album, recorded for a standing-room crowd in the relaxed atmosphere of the Jazz Workshop, Epic invited an audience to the Columbia 30th Street Studio in NYC (Epic was a subsidiary of Columbia Records) for the One Foot In The Gutter session. Uncertain as to which foot and gutter Bailey is talking about, it could well be, in subsequent order, his and one of those dingy clubs the jazz men of the classic age had to work in more often than not. It could also refer, of course, to the gutter of life in the USA, in which case the foot is a symbol of Uncle Sam’s snake-leather boot desperate to keep the black man lying on the ground. Any which way, the atmosphere is relaxed and the album is particularly well-recorded, sounding crisp, fresh and resonant.

Swing is the thing. And it’s immediately clear from note one that, if not spectacular on other fronts, Dave Bailey is a swinger. Cats instantly smell that kind of species. They want to play with swinging drummers only, and Bailey’s ride cymbal is stirring along proceedings rather nicely. There’s plenty of room to stretch out for Clark Terry, Curtis Fuller, Junior Cook and Horace Parlan on three mid-tempo tunes – the Bailey blues One Foot In The Gutter, Thelonious Monk’s Well, You Needn’t and Clifford Brown’s Sandu. The swift, tart and witty Terry, subdued, fecund and playful Fuller and angular Parlan succeed to raise more than a dozen smiles.

But if anyone shines brightly in the face of humiliation and constant threat of life in the muddy waters, it’s tenor saxophonist Junior Cook. The tone of Cook, at the time part of the classic Horace Silver line-up including Blue Mitchell, Gene Taylor and Louis Hayes, is a soul grabber: round, clean, medium-big, with a sly, sleazy edge, much akin to Hank Mobley or Tina Brooks. He’s finding the corners one didn’t anticipate were there in the labyrinth of bluesy, stylish phrases, spellbound by the innocence he’s discovering deep within himself of the child that’s thoroughly enjoying rides on the roller rink. Perhaps the organ grinds in his mind. Obviously, Cook is the cherry on top of a solid and laid-back blowing session.