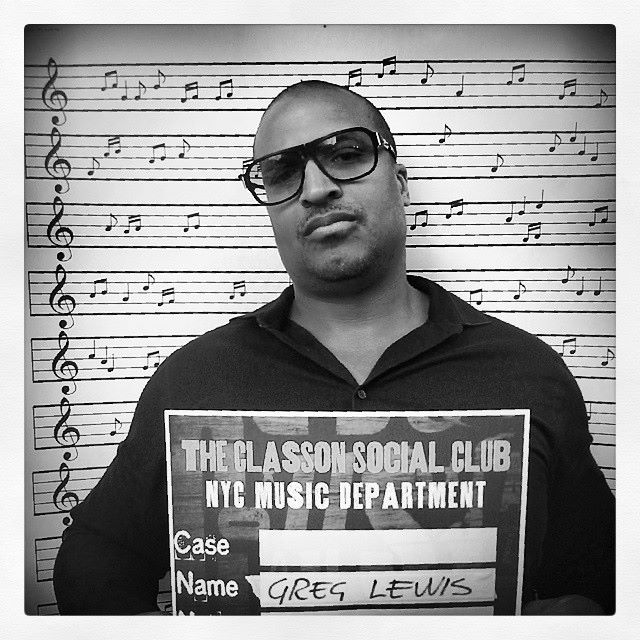

Gregory Lewis is Organ Monk, a passionate champion of the dazzling catalogue of Thelonious Monk. “I hummed his melodies by heart as a kid and played them for the girls in high school.”

Ever since the organist and pianist’s first album, 2011’s

Organ Monk, the beginning of what seems to have become a lifelong dedication to interpreting the music of Thelonious Monk with the Hammond B3 and C3, Lewis has gained plenty attention. Few have tread this path since Larry Young, a major inspiration for Lewis, recorded the epic

Monk’s Dream in 1964. No one has transposed the work of Monk to the organ with the distorted twist of the 48-year old fixture on the New York jazz, blues and funk scene, whose grasp of the wonderful compositions of the modern jazz genius is spot on and whose gritty, dynamic approach updates them excitingly for the 21st century. The hi-octane energy of Lewis works through in his live performances, where the audience is certain to witness Lewis hanging over his keyboard like a tiger over his prey. But the organist tries a little tenderness as well, occasionally caressing the organ like a vet stroking a wounded kitten.

Lewis is currently preparing the release of his fifth Organ Monk album. His latest album, The Breathe Suite, still lingers in the mind. A tour de force, it’s a mix of elaborate tunes, colorful organ playing and a twisted, groove-meets-fusion-type edge. The provoking set of Lewis compositions, including titles as The Chronicles Of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, boldly addresses the ongoing troubles of African-Americans in American society. Understandably, it’s been the grimmest theme during the telephone conversation Flophouse Magazine had with the candid, both serious and cheerful New York Native about his career and inspirations.

FM: ‘You were born in New York City. Which borough?’

GL: ‘I was born in Queens. And grew up there.’

FM: ‘I heard that you were into hiphop as a teenager, even prowled the streets as a human beatbox. Did you also play piano around that time? At what point did jazz and the piano come into your life?’

GL: ‘My father was a pianist, on the side. He had a lot of records of Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane and Bud Powell. As kids, we grew up to the sounds of Coltrane every Saturday morning and danced and ran around.’

‘In my teens, I liked the music that was on the radio, like Sugarhill Gang. I was playing piano, but nothing crazy serious, it was more like something to do. Then I got into the human beatbox thing in high school. But I got seriously into music because I noticed that the girls used to like it when I played the piano. I had many interests, the first album I bought, for instance, was by Funkadelic. But simultaneously, I was always listening to Monk and I was able to sing all these melodies, because my father played them all the time. Unfortunately, he died when he was 49, when I was 9. My mother says that he lives through me, because I’m doing what he always wanted to do.’

FM: ‘What was your father’s occupation?’

GL: ‘He did a lot of odd and end jobs. He played music and performed in his spare time. There were always friends who came by and they would go into the other room, listen to music, have a ball.’

FM: ‘So you liked hiphop, funk, and at the same Monk and Coltrane were everywhere at your quarters.’

GL: ‘Yes, it was part of our culture. We would go to my uncle and he would put on jazz and learn us to play chess.’

FM: ‘What triggered you to play jazz? Was hearing Thelonious Monk the event that essentially convinced you to become a musician?’

GL: ‘I got to thinking when people started to ask me how I knew all those melodies. They always asked, “hey, where did you learn that Monk stuff?” For some reason, back in the eighties, people knew who Monk was, but it seemed like they weren’t into him like today. Being a teenager that knew those tunes by heart, it got me into the New School Jazz Program. I didn’t know many other tunes. I was playing Monk’s music for the girls in school. “Oh, you know Thelonious Monk, you’re like a different kind of guy!” (laughs, FM) They would say: “Well, Greg’s a jazz guy, you know.” Playing Monk kind of came natural to me. Certainly his rhythm. Even to this day, when I arrange someone to sub for me, he might trip over these rhythms that Monk threw down.”

FM: ‘What kind of gigs did you do initially?’

GL: ‘When I was 16, I performed Prince songs. I loved Prince. Of course! We all wanted to be Prince after seeing Purple Rain. I did funk gigs in the neighborhood. My first professional gig in jazz was at age 18 with a group called The Family. It was founded by an artist who’d been in jail for doing heroin. Cleaned-up, he wanted to do something nice for the inmates. So we played in prisons. That was quite an experience. Then I started taking lessons from Gil Goggins. (Goggins played, among others, on the session that spawned the Miles Davis Vol. 1 & 2 albums, FM) Goggins was a really great pianist. He showed me how Monk actually played compositions like Trinkle Tinkle, which blew my mind. I had the right rhythm but a few wrong notes! He taught me a lot and also sent me to gigs.’

FM: ‘It was through Goggins that you got into organ playing, right?’

GL: ‘Yes, that’s a funny story. Goggins didn’t tell you what kind of gig it was, you just had to obey and show up! (chuckles, FM) Goggins sent me to a gig as a substitute. However, it turned out to be an organ performance. There was no piano, which presented a problem. I had never touched an organ in my life. Nevertheless, I fulfilled the obligation. I didn’t know how to handle the machine and fell flat on my face! But I was intrigued. From that day on, I puzzled out the functioning of the organ: the touch, bass pedal lines, drawbars. It took me approximately six months to fully master the Hammond organ.’

FM: ‘Did you got tips from other organists?’

GL: ‘Well, there was a real selfish thing going on in New York back then. I would go to a session where George Benson always went when he was in town. He’d park his Bentley on the curb and nobody, not the police anyway, would bother because it was George Benson! He would play, the organist would get up and notice that me or someone else wanted to sit in. The organist would push all the stops, so that you couldn’t figure out his secret. I would sneak behind, check out the stops and drawbars, memorize and then try at home!’

FM: ‘That’s pretty ludicrous! Then what did you do, study records?’

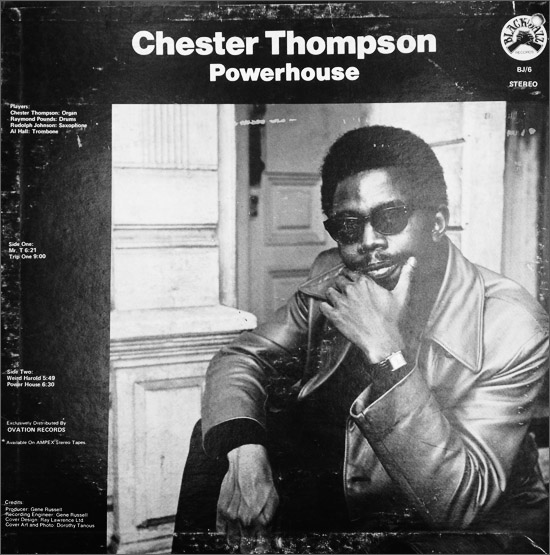

GL: ‘Yes, I studied practically everyone, from Jimmy Smith to John Patton. I checked out a lot of Chester Thompson, the funky stuff he did with Tower Of Power. Squib Cakes, whoa! And I loved Powerhouse, his solo album. Those grooves were crazy. I also loved the older cats, the r&b-drenched cookers, like Bill Doggett. But the one that blew me away, and I guess helped creating Organ Monk, was Larry Young. Monk’s Dream from Unity, where he played the duet with Elvin Jones, (Lewis hums the melody, then proceeds to play it at the organ in his practicing room, FM) hit me like a lightning bolt. I purchased all his albums. Well, mostly CD’s, the records were hard to find!’

FM: ‘How would you define your style?’

GL: ‘One thing, I was never good at copying. I was always taught that copying is no good, rightly so. As far as playing Monk is concerned, it was self-evident that my style went quite the other way. Perhaps because of the ingrained funk and groove. I met Donald Byrd and he told me: “That ain’t what Monk did!” I was like, “So what did he do?” Byrd answered: “I don’t know but that ain’t it!” Haha! I always felt, if I can get the rhythm, I don’t have to worry about the notes.’

‘To be honest, I just try to have fun with sound, dynamics. My style really developed after I started believing in myself more at a certain point. During the embryonic stages of Organ Monk, some people were still questioning my obsession with Monk. But some favorable reviews of my first album gave me a little boost. The feeling that I was on to something.’

FM: ‘How much time do you strictly devote to jazz?’

GL: ‘As much as I can. I practice a lot and perform regularly. I have also always played a lot of spirituals, gospel. I play at church meetings or tour with gospel groups. Then I try to incorporate it in my playing. A no-brainer, of course. When you throw that stuff out at the audience after you’ve played Monk, their minds get blown away!’

FM: ‘You mean, it’s a logical switch from one to the other?’

GL: ‘It’s intertwined. Playing spirituals grabs people. I play Testifyin’ by Larry Young in church. The signature line, the descending four measures at the end of the tune, it’s very churchy. That’s why he called it Testifyin’, of course. I repeat that line, build up tension and every time the audience goes berserk!’

FM: ‘There were a few self-penned tunes on your Monk albums, but The Breathe Suite is your first album that consists entirely of original compositions. It was a step forward, stylistically and conceptually. I wouldn’t say the vibe is exactly angry, but upsetting, to say the least.’

GL: ‘Being African-American, I can relate to the horrific stuff that has been going on. I also had cops pointing guns at me. My father and mother instilled in us from when we were little that when a cop pulls you over, you freeze, because he will shoot you and will kill you. You do not move, you do not say anything, you do as he says, so you can go home safe. That’s the way I was raised. The cold-blooded killings of the last few years are crazy. It upsets me as an African-American citizen. As a human being. It should upset anybody. Unfortunately, America is still not my friend yet. Yes, I can make money here, play my music and travel the world. But it’s still not fair. There remains a lot of sabotage, like in getting regular stuff such as bank loans. I tell my kids that there’s a big world out there, we don’t have to stay here.’

FM: ‘Your bewilderment rings through on the album.’

GL: ‘Classic works like Coltrane’s Alabama and Mingus’ Fables Of Faubus have had their influence one way or another, on a subliminal level. Once I started writing with these provoking works of art in mind, the songs just poured out of me. I can at least put my discomfort in my music and I guess that’s what you’re hearing. I can’t protest because then I will be fired from my teaching job at university, go to jail and won’t be able to feed my kids. So I can’t offer a solution but I hope that the album sustains the ongoing discussions and creates awareness.’

FM: ‘There’s a new album coming up, right?’

GL: ‘I just finished the album with Marc Ribot, who also played on The Breathe Suite. The new album will be released at the end of the year and called Organ Monk Blue, including more blues-based tunes like Raise Four, Misterioso. We put a twist on those tunes, because, you know, Ribot likes the funk, the groove. And he’s a crazy guitar player. I had a lot of fun playing with him because he’s nuts!’

Greg Lewis

Organist and pianist Greg Lewis is a mainstay in New York City’s jazz, blues and funk scene and tours abroad with gospel groups. As accompanist of several blues artists, his cooperation with singer Sweet Georgia Brown is striking. His thorough background in modern jazz – Lewis was teached by past masters Gil Goggins, Walter Davis Jr. and Jaki Byard – and love for groove music has resulted in a distinctive identity as an organist. As Organ Monk, Lewis has recorded a number of albums containing Hammond organ interpretations of Thelonious Monk’s music. His fifth album, Organ Monk Blue, will be released in December, 2017.

Selected discography:

Sam Newsome’s Groove Project, 24/7 (2004)

Organ Monk (2011)

Uwo In The Black (2012)

American Standard (2013)

The Breathe Suite (2017)

Check out YouTube clips of Greg Lewis, drummer Jeremy “Bean” Clemons and guitarist Ron Jackson playing roaring versions of Monk’s We See and Trinkle Tinkle.

Go to the website of Greg Lewis here.