Sonny Stitt suffered from the constant comparison with his friend Charlie Parker. Fact is, former manager of Ray Brown, Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven explains, that The Lone Wolf, contrary to common belief, already played bebop before he’d ever met Bird. A long-awaited debunking of myth.

You read about the nomads in North-Africa in history books. Or see them on tv on Discovery Channel. Weather-beaten people with leathery, wrinkled, red faces, dressed in full desert regalia, long robes from neck to feet, ingenuously arranged turbans on their heads. They’re wobbling on camels from dune to dune, finally reaching a tiny bit of half-fertile land, settling for a while, then moving on to the next challenge. Minding their own business. Until somebody takes them away as slaves. Or hires them as a tourist attraction below union scale.

The similarity with jazz legends is striking. You read about them in history books as well or, if you’re lucky, see them on public tv in a documentary, most likely on the European broadcasting systems. Somebody might give you a tip to go see the Miles Davis documentary on Netflix, featuring various fellow legends as supporting roles. This is the only way to know about them because, for various reasons, one being that America still hasn’t come to terms with the implications of an indigenous art form that simply by being itself defied white supremacy, the history of jazz is still largely absent from the curriculum of the educational system in the USA. (Let alone the history of serious rap and hip-hop, which was partly fueled by jazz and the most extreme – extremist – Afro-American outing in the history of American musical culture, essentially completely alien to WASP teachers, parents and kids and dealing with matters too scary to touch.)

In Hollywood, jazz is a tourist trap. To date, the jazz artist hasn’t been depicted on the big corporate screen in the manner he or she genuinely moves or behaves. Not even once. (Bird? Well… with all due respect: no) The latest effort was the jazz part of Babylon. Not quite. Unless professional jazz musicians are featured, e.g. Jerry Weldon and Joe Farnsworth in Motherless Brooklyn, these efforts are fruitless. (Not counting the indispensable European indie flick Round Midnight with Dexter Gordon)

So far, so bad. If poverty of portrayal is omnipresent, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that education falls short.

The jazz legends lived a truly nomadic life. Though they rarely if ever traveled with family. Jimmy Forrest worked on the riverboat in the band of the enigmatic Fate Marable. Up and down the Missouri and the Mississippi rivers time and again. Arnett Cobb journeyed with the so-called territory bands in the Mid-West, dust everywhere, in his nose, ears, crotch, brain. Duke Ellington worked around the clock, somewhere, somehow. He sat beneath Harry Carney in the car and traveled more miles on the American highways than Boeing 747’s fly over the oceans in their life span.

Charlie Parker, The Bird. Quite the wanderer in his all-too short and turbulent life. Sonny Stitt, The Lone Wolf. He liked to travel alone from East to West and North to South, picking up local rhythm sections and hard cash.

Speaking of Bird and The Lone Wolf. Whom crossed paths occasionally in their lives. Famously the first time, in 1942. Do you remember that story? Good one. Great jazz lore. Initially, it was chronicled by former promotor Bob Reisner in his book Bird: The Legend Of Charlie Parker in 1962. The story was quickly adopted by Ira Gitler for his liner notes of Stitt’s 1963 album Stitt Plays Bird. And repeated by critics and fans to this day.

However, Reisner and the herd forgot to mention or were ignorant of one thing. To be precise, nothing less than the punchline.

Early in his career, when he was 19 years old, Stitt played in the band of singer and pianist Tiny Bradshaw. Stitt had heard the records that Charlie Parker had done with Jay McShann and was anxious to meet him. Finally, one day, the band reached Kansas City, Bird’s place of birth. (see picture of Kansas City’s club-filled black district around Twelfth Street during the era of political boss Tom Pendergast below) Stitt: “I rushed to Eighteenth and Vine, and there, coming out of a drugstore, was a man carrying an alto, wearing a blue overcoat with six white buttons and dark glasses. I rushed over and said belligerently: ‘Are you Charlie Parker?’ He said he was and invited me right then and there to go and jam with him at a place called Chauncey Owenman’s. We played for an hour, till the owner came in, and then Bird signaled me with a little flurry of notes to cease so no words would ensue. He said: ‘You sure sound like me.’”

That’s it. That’s the official story. But it ends prematurely.

Because Stitt retorted: “No, yóu sound like me!”

“Yeah!” says Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven. “It’s amazing that none of the people in the business cared to tell the real story.”

(Stitt; Bird; Twelfth Street, Kansas City)

Swiss-born Jean-Michel Reisser was nicknamed “Beethoven” by the legendary Harry “Sweets” Edison. Son of a serious record collector that befriended jazz legends in the 1970’s, Jean-Michel sat on the lap of ‘uncle’ Count Basie as a three-year old kid. He eventually befriended Basie, Ray Brown, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Max Roach, Jimmy Woode, Milt Hinton, Sonny Stitt, Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Jones, Jimmy Rowles, Alvin Queen and various others. A savvy cat, he was hired as manager by Ray Brown. Besides managing Brown, Jean-Michel produced hundreds of records, tours and jazz documentaries. He has retired from the business now, lives in luscious Lausanne and, as passionate about his beloved art form as he’s ever been, is an enlightening jazz causeur.

“I would be stupid not to overwhelm all those legends with questions while they were still living and breathing. That way, I heard a lot of stories, directly from the source.”

Sonny Stitt, though, was rather reticent. “He was a great guy, but didn’t talk much. You had to take him by the arms and say, ‘hey motherfucker, I have some questions! He was the kind of guy that liked to drink and smoke and relax after a concert. It was only privately that Sonny ultimately got down to conversating about music.”

The punchline raises multiple issues. About the ignorance of the press. (Though Gitler, as we’ll see, spitballs something interesting at the issue.) About the mystery of parallel inventions in art. And, not least, about Stitt’s reputation and life. Much to his dismay, Stitt had to deal with comparisons with Charlie Parker all his life. Small wonder, since Stitt has always been a straight-ahead bop saxophonist, variating, apart from various commercial records, largely on the prevalent Tin Pan Alley changes and bebop’s contrafact compositions. However, a mere cursory afternoon of comparative listening between Stitt and Parker will reveal largely differing personalities to all listeners that trust their ears, whether beginners or aficionados.

Stitt’s a thoroughbred. Fine horse, plenty bulging muscle, shiny brown manes. Charging out of the gate, running powerfully but smoothly, eye on the finish line. Goal-oriented.

Bird’s a pinball at the mercy of a pinball wizard. It is eloquently maneuvered on the plate. Then, with a sudden push, it is smashed through the glass, careening around the arcade and miraculously jumping back into the machine.

No, yóu sound just like me!

Come again?

Reisser-Beethoven: “That’s the truth. It’s what Sonny told me when we talked about his meeting with Parker. Significantly, many people have told me about their interaction with Sonny. First of all, Ray Brown. Ray met Sonny in 1943. Ray said that he hadn’t heard about Parker until a bit later. He said, ‘I heard this young guy playing things I never heard before. Everybody says he’s playing like Bird, I said, no way. Sonny always had his own style’. Hank Jones played with Stitt in 1943 and he told me the same story. J.J. Johnson as well. He said he’d never heard about Bird until 1944, but he’d already played with Sonny Stitt: “This motherfucker had his style. He didn’t play like Parker. He played in the same vein, but it was different.’ Stan Levey told me a similar story.”

Vein is the word here.

Reisser-Beethoven continues: “This is the way of the arts. You sometimes see it happening in painting, that two great painters arrive at a similar concept. It works this way in music as well. For instance, the late Benny Golson explained to me that he composed a lot of tunes that he thought were pure originals but found out by listening to the radio that others had reached the same conclusion, without ever hearing Benny’s drafts. As far as the story about Stitt and Parker goes, Parker hadn’t totally arrived at his original style when he played with Jay McShann. It was only in 1944 when he had fully developed bebop harmonics. Stitt arrived on the scene a bit later and in the public eye and everybody said that he played like Parker. But historically, this is not the case.”

It is the way of the arts but also extends to other areas. Politics and social history, for instance, with strings of misunderstanding attached. Take Martin Luther King’s iconic I Have A Dream speech. Contrary to general belief, King didn’t invent the groundbreaking oneliner. He’d heard Prathia Hall, daughter of Reverend Hall, utter those words in a remembrance service in church after an assassination on black citizens. King used the sentence in subsequent speeches but it didn’t catch on until he so imposingly integrated it in his speech at the march to Washington, urged by singer Mahalia Jackson.

Back to our musical icons. Paradoxically, Reisner and Gitler mention an occurrence that backs up the idea that giants like Parker and Stitt arrived at the same musical conclusions apart from each other. (In this respect, it should also be noted that drummer Kenny Clarke worked on new rhythms in the very early 1940’s, a glimpse of the congruency of ideas of Parker, Gillespie, Clarke, Roach, Monk, Pettiford, Mingus, Powell in the mid-1940’s) Reportedly, Miles Davis saw Stitt coming through St. Louis (Davis’s birthplace) in 1942 with Tiny Bradshaw’s band, ‘sounding much like he does today as far as general style is concerned’. Gitler says: ‘We don’t know whether this was before or after the Kansas City confrontation, but Stitt has long insisted that he was playing this way before he heard Parker.’

Chockfull of lore, Gitler’s liner notes of Stitt Plays Bird (by the way, a record with some stellar solos by Stitt, regardless of the underwhelming band spirit) also mentions something that Charlie Parker supposedly said to Stitt a little while before his death in 1955: ‘Man, I’m not long for this life. You carry on. I’m leaving you the key to the kingdom.’

Epic. Lord Of The Rings-style. However, nobody in his right mind believes Bird to be capable of uttering such pompous near-last words. ‘Please pass that piece of lobster,’ seems more likely. Or, in a more serious friend-to-friend/father-to-son vein, ‘I urge you not to do as I did, stay away from the needle’.

In fact, Bird did say something of the sort to young disciples, that didn’t listen and with few exceptions got hooked. Nothing of the sort was advised to Sonny Stitt, though, who lived with his own demons and did time in Lexington, Kentucky in 1947/48. Precisely at the time that bebop gained nation-wide traction. Bad luck. Reisser-Beethoven: “I’m sure that his being out of the public eye was a setback, but his main problem was criticism. He suffered from big depressions throughout his career. Everybody presented him as a clone of Charlie Parker. It was problematic. He wanted to quit many times. Eventually, he alternated with tenor saxophone. Dizzy Gillespie came up with this idea in 1946, when Sonny was in Dizzy’s band. Suddenly nobody said anything about Bird! Although he played the same lines, chords, improvisations. Dizzy said to me that, when Parker didn’t show up, he’d either call Lucky Thompson or Sonny Stitt. He loved Sonny Stitt.”

“In his view, Norman Granz saved his career. Granz took him out on the Jazz At The Philharmonic tours. He recorded him with Dizzy, Sonny Rollins and produced all those Verve albums. Sonny considered his Verve albums as the highlight of his career; notably Sits In With The Oscar Peterson Trio, New York Jazz, Plays Arrangements From The Pen Of Quincy Jones. He also believed his albums in the early 1970’s with Barry Harris, Tune Up, Constellation and 12! to be among his best.”

And so, the nomads traveled from East to West, North to South, dark-skinned birds and lone wolfs roaming from one asphalt jungle another, sometimes jubilant, rejoicing notes brimming with blues and Debussy, as excited as kids on a funny farm, sometimes shivering, hiding in a torn raincoat, at the end of the rope and the track. Charlie Parker and Sonny Stitt crossed paths more than once. Reisser-Beethoven: “Allegedly, they met several times. As far as I’ve heard, they were good friends. Charlie Parker didn’t say anything bad about Sonny’s style, no way. Dizzy said that sooner or later the critics were bound to put walls between them. It’s not only like that in music. But also in politics, religion, history. All too often, one guy tells the so-called definitive story and the rest follows it blindly. It’s a pity.”

Sonny Stitt

Here’s Stitt Plays Bird: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0I2Lcnn_hLs

Here’s I Remember Bird: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMEpRUTE_no&list=OLAK5uy_nuKI1RZPqZVIsRMGYW7kGI9RNO1uuxoRs&index=2

Gideon’s Bible

Saxophonist Gideon Tazelaar, 19 years old, is one of Holland’s major jazz talents. Leaving his options open for the next five years, Tazelaar at least is positively sure of one next step. “Next year, I’m going back to New York.”

Tazelaar stayed in New York once before in 2015, joining sessions, held spellbound by the remaining legends of modern jazz like Harold Mabern, Jimmy Cobb and Jimmy Heath. “I saw Roy Haynes twice. That was magical. I’ve never seen anything like it. He played with his quartet plus Pat Metheny. But I only watched Haynes behind his drumkit. Everything he did was so spot-on. I was often wondering where he was, time-wise. But I’ve come to the conclusion that, really, what Haynes played was the time. Somehow, Haynes was the music. He went into a tapdance routine, which, astonishingly, revealed the entire jazz tradition. And of course it was special to see someone perform who goes way back to Charlie Parker, Monk, Coltrane… Even to Lester Young.”With a hesitant timbre in his voice, as if ashamed of his good fortune: “And I had breakfast with Lee Konitz. He’d been my teacher once in Germany and said to call me whenever I was in town. That was awesome. We were at his place. I got a little quiet… But he kept talking, so that was perfect! Konitz said that he felt uneasy recording Motion, because it was his first encounter with Elvin Jones. But in hindsight he thought the results were rather satisfying… I’ve learned lots of things from Konitz. Musical stuff, because he’s a genius, but also about attitude. He doesn’t seem to have an all-encompassing explanation of his musical choices, except that they develop from a search for beauty. He really gives you the idea that the purpose is to follow up on what you love and dig deep into that well.”

“I’m really looking forward to another stay in New York. I will be going for about one year and maybe study at some music college, check out older musicians. Men like Reggie Workman and Charlie Persip still teach. The division between styles is less astringent than here. I’ve noticed this during some sessions with Ben van Gelder and American colleagues, they blew me away playing stuff ranging from blues to Bud Powell to avant-leaning compositions. In The Netherlands, people sometimes encounter me as that supposedly ‘promising musician’. They are friendly, responsive. That’s ok, for sure, people have helped me out a lot. But I haven’t really been at the bottom of the ladder, you know what I mean? And I think it would be beneficial to my musicianship if colleagues kick me in the butt now and then. And they will in New York, regardless of my age, I’m sure! I’m looking forward to it.”

Meanwhile, Tazelaar performs as much as possible. “I try to do my bit of study as well. My mindset changes continuously, so I press myself to study with focus. I like so many things, therefore I have to structure things to really get to the heart of the matter and not be distracted. I’m making schemes for two months in advance.”

Tazelaar grins, his downy, dark-brown moustache twists. He pulls himself from his couch, finds a notebook between the rubble on his desk, sits down and proceeds to read his upcoming scheme. If anything, an intriguing hodgepodge of activities. Among other things, Tazelaar is going to practice clarinet again, learn a Bud Powell solo on piano, read the biography of Sidney Bechet, finish an original Tazelaar tune, study the theory of Schönberg, harmonize chorals in Bach style and, last but not least, learn 3 solo’s of Frank Trumbauer, Bix Beiderbecke and Louis Armstrong each. Monomania. Eagerness. A young man enthralled by the beauty of America’s sole original art form as well as the works of classical composers who often were admired by the jazz legends.

Recognition for Tazelaar has come early. Already playing saxes as a kid and adding clarinet in the process, Tazelaar has been in the limelight ever since. He played at The Concertgebouw at the age of 8, enrolled at the Conservatory of Amsterdam when he was 14, passing maxima cum laude at 18. If he may choose to, Tazelaar can put a nice rack of prizes on his mantle and has been a regular fixture in the club circuit and at the North Sea Jazz Festival. Sitting under a framed portrait of John Coltrane, the eyes of the bright college student-type Tazelaar twinkle when looking back upon his contribution to a tenor summit at the Bimhuis last March, including Rein de Graaff, Eric Ineke, Eric Alexander, Sjoerd Dijkhuizen and Ferdinand Povel. “So inspiring to play with the elders. And especially great to share the stage with Ferdinand, who has been my teacher for a long time. He teached me a lot just by talking about jazz, and especially about harmony. He plays so beautifully. I think I nicked quite a few of his phrases.”

Asked about his playing style, the contemplative, even-tempered Tazelaar is cautious to ill-define matters. He patiently weighs his words on a scale, much like the way a thrift store owner would count the coins that a bunch of candy-buying kids have scattered on the counter. Lots of ‘umms’ and ‘aaahs’. The sound of a brain cracking. “Tough question. I don’t think I play in one style. I experience it as versatile, depending on the people I play with. It puts the big picture of a group in perspective, I don’t feel the need to deliberately go against the grain in a group, style-wise. Arguably, it’s all part of my development. I might one day stick to something that feels destined to be played. In general, I have my influences as well, of course.”

Aside from Povel, Tazelaar is fond of saxophonist Benjamin Herman, having thrown himself headlong into the weekly sessions at Amsterdam’s De Kring. “Basically, I’m a very critical and self-critical guy. Genes, I guess. That’s ok, critique’s a constructive asset. But it tends to stress negative aspects as well. Benjamin focuses on good things, he’s able to find interesting, quirky aspects in different kinds of music. That’s positive. And better for your mental health.”

Tazelaar has been picking some positively quintessential influences at an early age. “I’m listening to a lot of classic bop and hard bop saxophonists, but up until now I’ve always come back to my main men: Bechet, Parker and Coltrane.”

“I’m always interested in the transitional periods in the careers of musicians. Those recordings of Bechet in France in the late forties are great. (Tazelaar refers to Bechet’s May 1949 recordings with either the Claude Luter Orchestra or Pierre Braslavsky Orchestra) He’s playing New Orleans-style, of course, but hints at things to come as well. He would be an influence on Coltrane.”

“I really like both early and late Coltrane. Early or late, the integrity and inspiration are always there. Lately I’ve been listening to Coltrane with Miles Davis in 1960, near the end of Coltrane’s stay with Miles Davis. There’s this live version of ‘Round Midnight, it was on bootlegs I think. Coltrane goes from one extreme to the other, but keeps referring to the melody in between, it’s fantastic.”

“Parker’s playing on Dizzy Atmosphere (February 28, 1945, Savoy MG12020, FM) is also a good example of tension between old and new. Swing and bop, in this case. There’s this swing rhythm section including bass player Slam Stewart (and Clyde Hart, Remo Palmieri and Cozy Cole, FM) that swings like mad. Parker and Gillespie are inventing the bop language on top of it. But the thing is, Parker blends well with that old style, because he lived in that period as well, naturally. He knew where it was at. In these performances, Parker constitutes the best of two worlds, he fits.”

Gideon Tazelaar

Gideon Tazelaar (Hilversum, 1997) has been performing from age 8, appearing at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Prinsengracht Concert. Since his early teens, Tazelaar has been a sought-after player, performing with the Dutch Jazz Orchestra and the Jazz Orchestra Of The Concertgebouw as well as at The North Sea Jazz Festival, and has been cooperating with, among others, Benjamin Herman, John Engels, Peter Beets, Ben van Gelder, Dick Oatts, Eric Alexander and, in the summer of 2016, organist Lonnie Smith. Tazelaar won the Composition Award of NBE in 2006, the Prinses Christina Jazz Concours in 2012 with his quartet Oosterdok 4 and the Expression Of Art Award in 2016. Nowadays, Tazelaar regularly plays with his Gideon Tazelaar Trio, which includes bass player Ties Laarakker and drummer Wouter Kühne.

Check out Gideon Tazelaar’s website here.

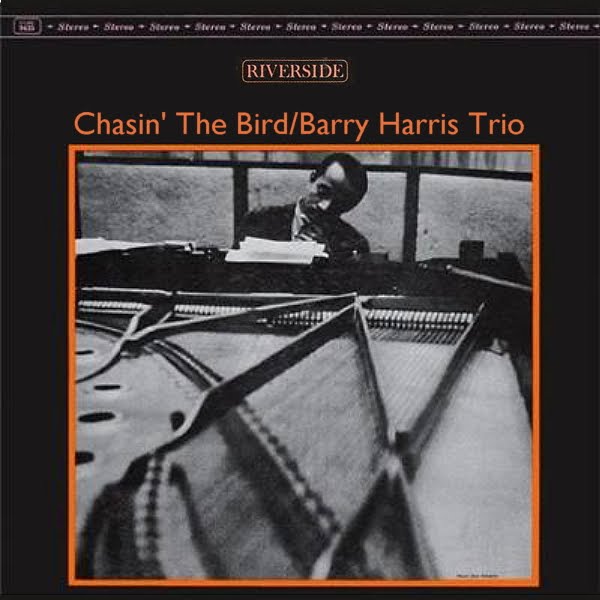

Barry Harris Chasin’ The Bird (Riverside 1962)

An important part of the spirit of jazz, writer and critic Nat Hentoff once wrote, is the independent character of the jazz musician. Improvising involves taking risks while simultaneously holding on to one’s particular style and ideas. It, ideally, takes a seizable amount of stubbornness and discipline many laymen cannot help but find admirable. A classic example of such endurance is Thelonious Monk. It took the great pianist about fifteen years of struggle, poverty, misunderstanding and denunciation before Monk’s ‘brilliant corners’ were finally part of jazz’ main route. A lesser known example of stubborn dedication is pianist Barry Harris.

Personnel

Barry Harris (piano), Bob Cranshaw (bass), Clifford Jarvis (drums)

Recorded

on May 31 and August 23, 1962 at Plaza Sound Studios, NYC

Released

as RLP 345

Track listing

Side A:

Chasin’ The Bird

The Breeze And I

Around The Corner

Just As Though You Were Here

(Back Home Again In) Indiana

side B:

Stay Right With It

‘Round Midnight

Bish Bash Bosh

The Way You Look Tonight

Nowadays, the elderly Harris is an authority on the works of Monk and Bud Powell. In the seventies Harris lived alongside Monk at the residence of the legendary jazz mecenas, baroness “Pannonica” de Koenigswarter in New York and from the mid-fifties onwards fervently studied and interpreted Monk, Powell and Charlie Parker. It says a lot about his background. Believing bebop to be synonymous with jazz more than any other development, Harris made it his mission over the years to talk about its meaning and teach its theory to new generations in universities and music colleges around the world and in the Jazz Cultural Theatre Harris has founded in the eighties. It took some perseverance, and little financial rewards. But as friend and tenor saxophonist Jimmy Heath said a couple of years ago in The Guardian: “We started because we loved this music. Harris’ students pay very little because Barry is more concerned about spreading the music around than financial gain.”

Harmonically, Harris keeps in line with his examples Monk, Powell and Parker. His solo’s sound a lot like Powell, but are less frenzied and angered. Instead, Harris concentrated on a lithe yet occasional gutsy swing. An unusual bebop approach seldom found among second-generation colleagues. (Tommy Flanagan comes to mind) Chasin’ The Bird is Barry Harris’ sixth solo album and his fifth for Riverside. Furthermore, in 1962 Harris had built up an excellent resume as sideman with Cannonball Adderley, Donald Byrd, Johnny Griffin and Sonny Stitt. Nothwithstanding Harris’ faithful bebop tactics, there are touches in his style, notably his firm, bluesy left-hand accompanying of soloists, that he would use to effect thereafter in a number of hardbop sessions, chief among them Lee Morgan’s smash hit recording of The Sidewinder.

Chasin’ The Bird sports, among others, one Parker composition (Chasin’ The Bird), two standards famously injected with bebop logic by Parker (Indiana, The Way You Look Tonight), one classic Monk tune (‘Round Midnight) and a couple of bop originals by Harris himself.

On the title track Harris shows remarkable technique on the theme, creating elaborate voicings with both right and left hand running along swiftly. It sounds like Bach and it sounds like Bach-influenced Bud Powell. Harris’ solo has a great flow and is cleanly executed; he doesn’t play fast for fast’s-sake. Ballad Just As Though You Were Here is constructed of dizzying, cascading runs mixed with sweetly romantic statements. It’s followed up by Indiana. It goes at breakneck speed and Harris puts a lot of juice in a coherent solo.

Harris’ approach is controlled and is proof of a lot of thought. The Breeze And I, for instance, was constructed around a Latin rhythm without the common release into 4/4 time. It gives Harris the possibility to concentrate on and dig deeper into the percussive piano style he utilizes. Its percussive effect and relaxed but effective use of space reminds me of Duke Ellington’s combo work with Max Roach and Charles Mingus on the rare gem Money Jungle.

Harris uses a lot of Monkisms – rollicking scales and dissonance – on Monk’s ‘Round Midnight, but also creates mellow harmony. The Harris originals come off nicely. Bish Bash Bosh, particularly, is a contagious tune including a smart stop-time theme and repetitive, fiery sparks. The supporting group – bassist Bob Cranshaw and drummer Clifford Jarvis – really get into the groove here. They create a solid bottom as well as place sureshot accents throughout the album.

Bebop is not an easy music to perform meaningfully, let alone correctly. Barry Harris was well capable of handling bop’s legacy, and in the process embraced it with his own gentle and swinging flavour.