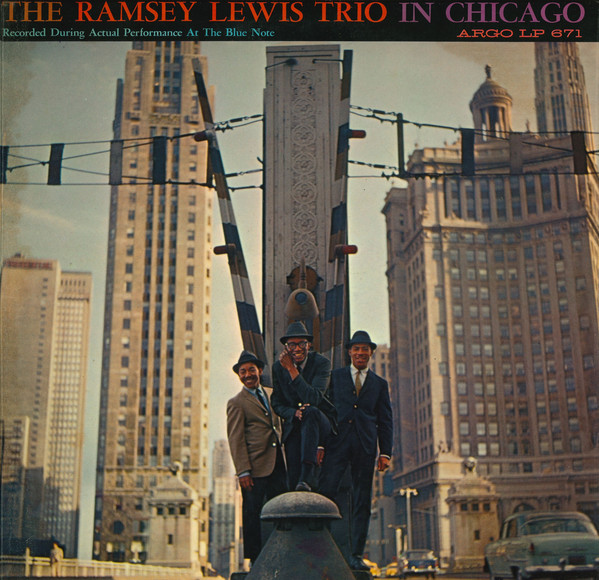

Before he hit big nationwide with 1965’s The In-Crowd, pianist Ramsey Lewis had delivered a string of Argo albums to an already notable fan base in the Mid-West. Among those albums is In Chicago, a typically dynamic and entertaining performance of the Ramsey Lewis Trio.

Personnel

Ramsey Lewis (piano), Eldee Young (bass), Red Holt (drums)

Recorded

on April 30, 1960 at the Blue Note club, Chicago

Released

as Argo 671 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Old Devil Moon

What’s New

Carmen

Bei Mir Bist Du Schön

I’ll Remember April

Side B:

Delilah

Folk Ballad

But Not For Me

C.C. Rider

There’s soul jazz and soul jazz. In the late 50s and early 60s, artists like Jimmy Smith and Gene Ammons spearheaded a movement of artists that presented both excellent and entertaining blues-based jazz to a largely Afro-American audience. Then Ramsey Lewis covered Billy Page’s The In-Crowd, which was a hit for Dobie Gray in 1963. His version, recorded at Bohemian Caverns in Washington D.C. in 1964, climbed the Billboard charts to #5 in 1965. From then on, coming immediately and in droves, colleagues followed his footsteps and interpreted a variety of contemporary soul songs and hits. Suddenly soul jazz, having taken ‘soul’ quite literally, also appealed to the white market place, with Ramsey Lewis at the helm. The pianist scored subsequent hits with Hang On Sloopy and Dancing In The Street.

With the exception of his early seventies output and mingling with the electric piano – Lewis focused on electric piano-driven fusion of smooth funk and jazz, releasing the Grammy Award-winning Sun Goddess featuring Stevie Wonder in 1974 – the style of Lewis more or less stayed the same throughout his career. And he cherished the foundation of long-running rhythm sections – first Eldee Young and Red Holt (1956-65), then Cleveland Eaton and Maurice White (1965-75). Never change a winning team and/or format. These duos, a bunch of steam locomotives, in constant motion, either holding back responsively or driving the tune through a brick wall, perfectly underlined the trademark style of Lewis. It’s a dynamic style imbued with gospel and blues feeling, propulsive but rarely if ever overcooked. It’s filled with lithe, rippling teasers that slowly but surely develop into Sunday sermon storms. Groove but with a bit of sensitivity that Lewis borrowed from influences like Ahmad Jamal. Lightweight? Yes, if one unjustly compares Lewis with Jaki Byard or Herbie Nichols. No, because when Lewis plays, the floor threatens to sag under the heavy toe-tapping of the audience.

In the late 50s and early 60s, the audience was also bound to go home with a smile after an evening of Ramsey Lewis music. Smiles abound, surely, on April 30, 1960, at the Blue Note club in Chicago. The Ramsey Lewis Trio played Old Devil Moon, What’s New, Carmen, Bei Mir Bist Du Schön, I’ll Remember April, Delilah, Folk Ballad, But Not For Me and C.C. Rider. A mix of standards, popular music and original blues-based compositions, practically each one of them marked by tension and release, effective devices from r&b and a lot of quiet thunder. Old Devil Moon is a lesson in how to begin a set. The piano introduction is lavish, then the band kicks in, pang! Such a tight-knit, urgent groove. That’s how to state your intentions! The trio’s version switches regularly between keys, which perhaps is a bit cheap but definitely keeps the listener on its toes. You think the gent and dame at the table noticed the changes of keys? Don’t underestimate the Afro-American jazz lover of the 50s and 60s, they knew their stuff, but they wouldn’t have cared less, as long as the stuff swings.

This was Chicago, hometown of Ramsey Lewis, and obviously the pianist would’ve had to strain to fuck up, in the city that up until that time had spawned the careers of Jimmy Yancey, Roosevelt Sykes, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Pinetop Perkins, J.P. Leary, Otis Spann, Walter Shakey Horton, Kokomo Arnold, Eddie Boyd, Willie Dixon, Jazz Gillum, Earl Hooker, Little Walter, Fred Below, Syl Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, Big Bill Broonzy, Blind John Davis, Magic Same, Otis Rush, Elmore James, Sunnyland Slim, Buddy Guy, Willie Mabon, James Cotton, Koko Taylor, Dinah Washington, Jerry Butler, Gene Chandler, Otis Clay, Etta James, Sam Cooke and many others. Most of them had migrated from the South, just like the audience, that was working hard by day in the big city factories, enjoying their night out as hard as they could. A tune like C.C. Rider, generating a lot of heat pretty much equivalent to the temperature that is developed from the blow of a hammer on a steel girder, sits well with such an audience. It probably was a request. At the end of the set, Ramsey Lewis humbly says that the trio, unfortunately, wasn’t able to play all of the requested tunes.

The In-Crowd was something else, a roaring, sure-shot mender of Ramsey Lewis’s destiny. But as In Chicago reveals, the particular Lewis swing during live performance was there from the beginning.

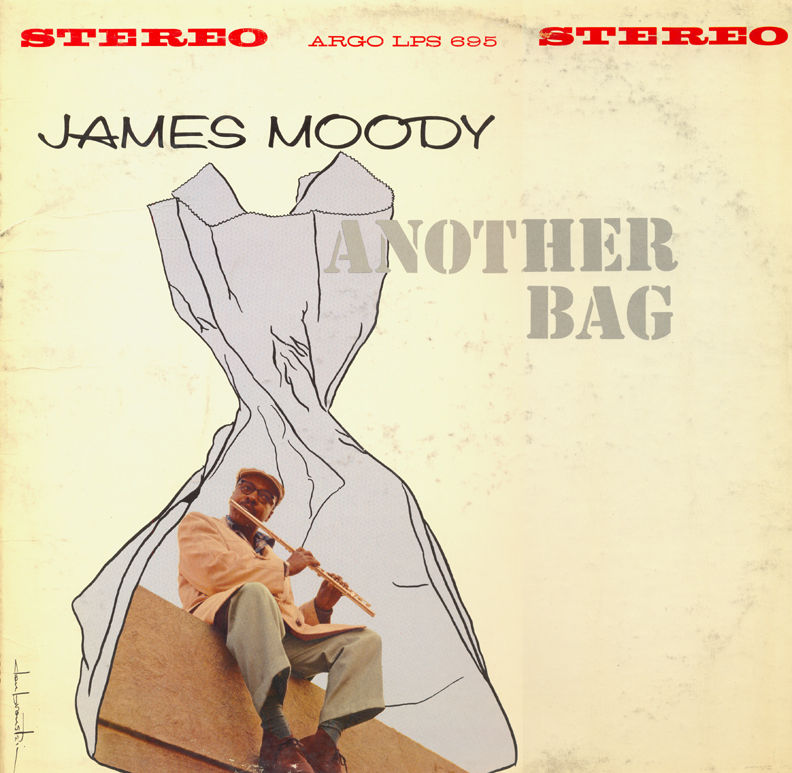

PS: Any doubt that this is the essential Ramsey Lewis record cover? It’s beautiful. Argo art is either beautiful, solid or plain silly. Look at those Johann Sebastian Bach sweaters. Only thing one can say is, they picked the right dude.