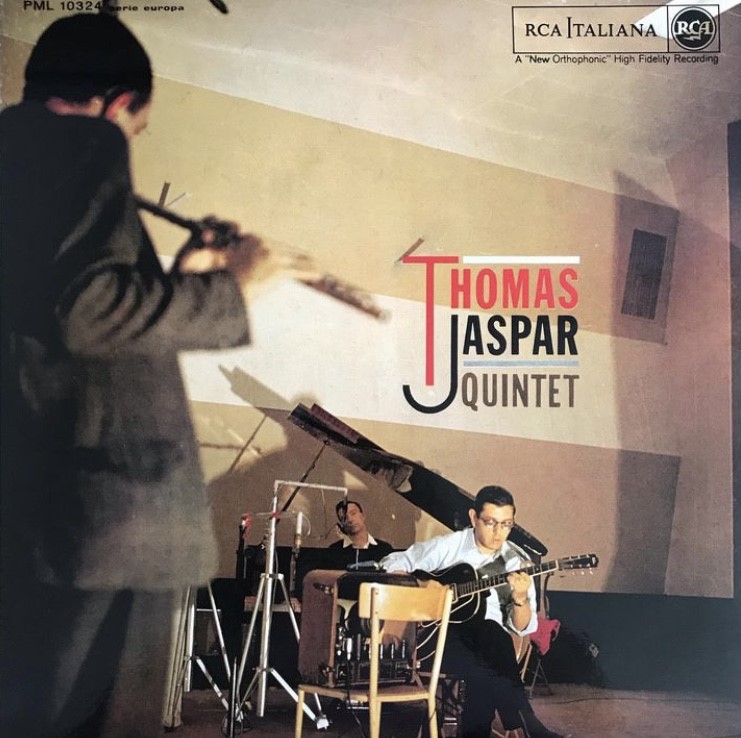

Theme for René.

Personnel

René Thomas (guitar), Bobby Jaspar (tenor saxophone, flute), Amedeo Tommasi (piano), Maurizio Majorana (bass), Franco Mondini (drums A1-3, B1, B2 & B4), Francesco Lobianco (drums A4)

Recorded

in October 1961 in Rome

Released

as RCA Italiana 10324 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Oleo

Theme For Freddie

Half Nelson

But Not For Me

Side B:

Hannie’s Dream

Bernie’s Taste

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes

I Remember Sonny

It was a little town close to the border of Belgium and approximately fifteen kilometers from my birthplace in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen in The Netherlands. There was a gypsy trailer camp. Me and a buddy, we must’ve been about 18 years old, I was a blues band drummer in my spare time, he was a talented guitar player already much better at his craft than I would ever be at mine, for some reason visited a gypsy family. There was a guy that played fabulous gypsy jazz. I believe that he was a nephew of Fapy Lafertin.

Typically, almost everybody at the camp played one instrument or another, from the cradle-young to the Methusalem-old. The camp was situated a stones’ throw away from the little town. About twelve trailers, made from brick, plastic and corrugated plate, were hidden from view by grey skies, silent back ways and fields of waving corn.

Whenever I think about or am listening to René Thomas, my mind is cast back to this afternoon. Thomas was neither gypsy nor gypsy jazz guitarist, but he had plenty, unmistakable gypsy feeling. For the gypsies, for Thomas, music is like eating a grape. Like tying shoelaces.

The soul of René Thomas lighted up in Liège, Belgium in 1926. Thomas loved the music of his fellow countryman, Django Reinhardt (there you have it) and besides swing jazz played ‘manouche’ in his youth. Around 1947, Thomas and friends like saxophonist and flautist Bobby Jaspar, saxophonists Jacques Pelzer and Jack Sels, bassist Benoit Guersin and drummer Rudy Frankel were obsessed with bebop and grew into one of the first European bebop units. Thomas thrived in Paris in the early 1950’s, mate among young lions as pianist Francy Boland and saxophonist Barney Wilen.

As soon as Thomas landed in New York City in 1956, he made a big impression. Until 1961, Thomas played with Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Jimmy Raney, Tal Farlow, Jim Hall, Zoot Sims, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Hank Mobley, Jackie McLean, Joe Henderson and Wayne Shorter. Everybody was crazy about his playing. Rollins, who featured the guitarist on Sonny Rollins And The Big Brass, said: “I know a Belgian guitar player that I like better than any of the Americans I’ve heard.”

Fruitful years in Belgium and Europe, marked by associations with Kenny Clarke and organist Lou Bennett, preceded a period of depression in the late 1960’s. Thomas stepped back into the limelight in 1970, again with Clarke and another organist, the fabulous Eddy Louiss from the island of Martinique. Then Stan Getz asked for his services. Enter a stellar band, featuring Louiss and drummer Bernard Lubat. Their legacy is preserved on a fantastic live album, Dynasty.

Sadly, Thomas overdosed and passed away in 1974 in Santander, Spain.

René lives! By God, a fabulous guitar player. Put on any of his albums or features as sideman, whether it’s early work as René Thomas Et Son Quintette, mid-career Riverside recording Guitar Groove, stints with Chet Baker on Chet Is Back or Lou Bennett on Echoes Of My Church or Ingried Hoffmann on Hammond Tales, Dynasty and his last recording, Thomas/Pelzer Limited with Dutch pianist Rein de Graaff, and notice his unmistakable solid sound and ringing notes. Not to mention, when he’s at his very best and stretches out, and here you need to check out some of the stuff on the fantastic CD-set Remembering René Thomas on Fresh Sound, which provides his best biographical sketch so far, seemingly endless strings of ideas, an originality that bustles with vitality and oozes a desire to break away from harmonic resolutions.

He seems exceptionally involved with his playing, really into it, digging in, peeking from the dark through the curtains, sun rays slipping in… Dark thoughts, cigarette smoke curling to the brown-skinned ceiling. Clean, electrifying lines seem to come so easily to him, and you see him hunched over his Gibson ES 150, hiding behind Coke-bottle glasses, modestly pouring out the sweat drops of his soul. He came from Charlie Christian and Charlie Parker and most of all was a disciple of Jimmy Raney, who was God for so many guitarists, and mind you, even influenced John Coltrane, but what sets him apart from the maestro, in my mind, is abundance of feeling. Emotive sparks.

Plenty sparks fly on the before-mentioned Guitar Groove, his best-known album, quite logically because it was recorded on Riverside and in the USA, but Thomas Jaspar Quintet definitely holds it own. It demonstrates the agility of the finest European jazz musicians and a gift for original songwriting. The band, consisting of another European giant, tenor saxophonist and flautist Bobby Jaspar, who contrary to Thomas built a solid career in the USA, pianist Amedeo Tommasi, bassist Maurizio Majorana and drummer Franco Mondini, performs the usual suspects that Thomas had played for years, Sonny Rollins’s Oleo, Miles Davis’s Half Nelson, But Not For Me, but also original tunes as Thomas’s Theme For Freddie, I Remember Sonny and Tommasi’s Hannie’s Dream.

Highlights? Every tune’s got something going for it. The way Thomas kickstarts his story of Oleo, lingering on a note, and using plenty of repetition, is daring and spontaneous and the way he constructs his solo in the process is even more exciting. Theme For Freddie is sweet and lovely, what with Jaspar’s flute playing, brimming with life in the sultry summer afternoons of Brussels, a tune oozing with the age-old culture of the good life. Hannie’s Dream is another very “European” ballad. There is hard swing and the hard tenor of Jaspar to be heard, while Cole Porter’s Bernie’s Taste is taken at brisk, sprightly pace. For good measure, Thomas tackles another lovely standard, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes, and him doing it solo, quite brilliantly I might add, adds to the variety of the program.

Although Thomas was still not a household name in the early seventies, his energy seemed undimmed. At that time, he was regularly coupled with the masterful Dutch drummer Eric Ineke, who played with Thomas between 1972 and 1974 in Dutch places like Utrecht, Zwolle and Laren and German cities such as Bremen and Wilhemshaven. (cuts from Utrecht and Wilhelmshaven ended up on Guitar Genius Vol. 1, good stuff regardless of the reverb-less mix) In his book The Ultimate Sideman and a big article that he himself wrote for the great Dutch jazz magazine Jazzbulletin, Ineke says:

“René was a very adventurous player who was not afraid to take some dangerous risks on the spot. His playing had an urgency which gave the music a forward motion, combined with a great swinging time feel and a lot of old-fashioned emotion. (…) I miss his playing, he was really responding to the drums, sometimes we were almost getting over the top.”

“René and his daughter Florence stayed at my place in The Hague. We had the night off and sat playing scrabble like a couple of good little church workers. René was very good at the game. Early next morning, guitarist Eef Aalbers was standing at the front door. He was dying to chat and play with René. René took his guitar and showed just how difficult that cadenza was that John Coltrane played at the end of the ballad I Want To Talk About You. He played it note by note from the top of his head. (..) The last time that we played together was in November 1974 in Café 19/20 in Amersfoort. Eef Aalbers had initiated this gig. Wim Essed was on bass. It was a night to remember. Emotions were running high and René and Eef played as if their lives depended on it. I would love to have a recording of this because it was unique: Eef Aalbers, young and hip super talent, together with René Thomas, a legend during his lifetime.”

“René Thomas was a humble personality and a unique guitar player, whose every note came from the depths of his soul. Belgium has put all but a couple of jazz stars on the map and René is unquestionably one of those.”

He remembers René. Giant of jazz guitar.