Da-da di-da-da-da, the crosseyed cat sang.

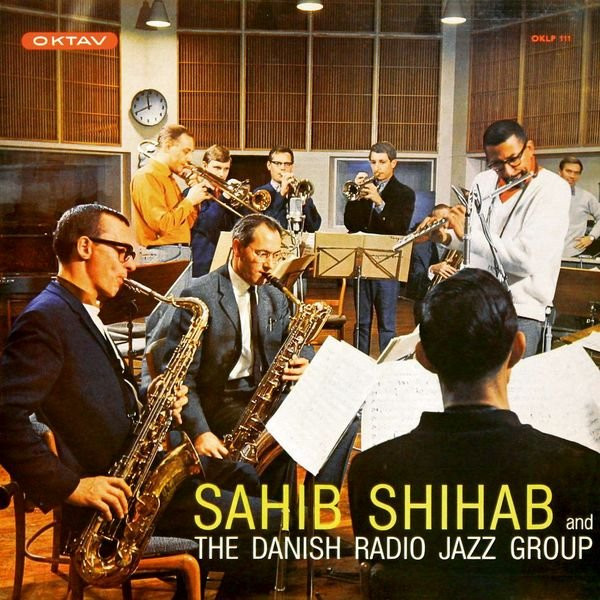

Personnel

Sahib Shihab (baritone saxophone, flute, cowbell), big band featuring a.o: Palle Mikkelborg (trumpet, flugelhorn), Bent Jædig (tenor saxophone, flute), Niels Husum (soprano saxophone, bass clarinet), Bent Nielsen (baritone saxophone, flute, clarinet), Bent Axen (piano), Louis Hjulmand (vibraphone), Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen (bass), Alex Riel (drums)

Recorded

in 1965 at Danmarks Radio

Released

as Oktav 111 in 1965

Track listing

Side A:

Di-Da

Dance Of The Fakowees

Not Yet

Tenth Lament

Side B:

Mai Ding

Harvey’s Tune

No Time For Cries

The Crosseyed Cat

It’s about time to spotlight Sahib Shihab, who creeped in the Flophouse premises as a sideman on Philly Joe Jones’s Drums Around The World, Milt Jackson’s Plenty Plenty Soul, Curtis Fuller/Hampton Hawes’s With French Horns and Howard McGhee’s The Return Of Howard McGhee. Plenty sizzling sidemen jobs. He played on records by Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Art Blakey and Thelonious Monk and spent a decade in the Kenny Clarke/Francy Boland Big Band.

Relatively unknown in his homeland probably because of his move to the European continent in 1965, Shihab nonetheless managed to make some slaps of vinyl as a leader in his own right. Jazz Sahib on Savoy in 1957, Sahib’s Jazz Party on Debut in 1963 and Seeds on Vogue Schallplatten in 1970 are, well… Sahib Highlights. Shihab lived in Denmark for ten years. A lot of recognition, a lot of work, a lot of good food and great women. And (almost) no discrimination and hostility. Hampton Hawes agreed but in his poignant autobiography Raise Up Off Me also expresses his doubts: “What are beautiful cats like this doing in European capitals? They should be back blowing at Shelly’s and the Half Note close to the source where the music was changing and evolving – things happening that might not reach Europe for years. If they stayed over here much longer they were in danger of becoming local.”

Sahib Shihab went back to the States in 1973 for three years, where he was born as Edmund Gregory in Savannah, Georgia and turned into one of the early boppers on baritone, alto and soprano saxophones and flute. Among those that comprised the source where the music was changing and evolving, Mr. Gregory was one of the first black artists to convert to Islam faith, an act that served as the most politically outright manifestation of the inherently progressive music that was bebop. Though we should be careful to address it as mere protest.

That was in 1947. Post-war frenzy. Commies the new enemies. Two decades later, with JFK shot through the head, Lyndon Johnson the new B-boy battling the Vietcong, The Beatles breaking through across the pond, Shihab was living in Copenhagen. That was the year of 1965. The year of, yes… another Sahib Highlight. Thé highlight? We’re talking Sahib Shihab And The Danish Radio Group, one American, a big bunch of Danish cats. Hell yeah, can’t get any better.

Tremendously swinging stuff. Without any reservation, a blast that oozes Ellington and Mingus, consisting of eight sassy compositions by Shehab. It kicks off with a solid walking bass and staccato horns, it’s Di-Da and a tenor saxophone says da-da-di-da-da. A vibraphone is added, someone plays a killer trumpet solo, someone quotes St. James Infirmary Blues. First thing one might notice is that this Danish platter sounds crazy good.

Second thing one might notice when we’re waltzing in Dance Of The Fakowees is that Sahib recruited a group of Denmark’s finest: Palle Mikkelborg on trumpet and flugelhorn, Bent Jædig on tenor saxophone and flute, Bent Axen on piano. Not to mention the greatest Danish bass player of all time, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen and superb drummer Alex Riel. The clarinet player is a first-class snake charmer. Someone plays killer trombone, a muted three-trumpet team returns to the Fakowees theme after a superb display of soft/loud horn section dynamics. Sophisticated but sleazy. Here’s one of the references to Ellington/Mingus. Did Sahib play with Mingus? Not on wax. He listened. Better said, heard. No doubt.

We have the breakneck speed of Not Yet, built around sparkling and booming drum melodizing. We have the balladry of Tenth Lament, vaguely resembling, ahum… Goodbye Porkpie Hat, showcasing a bold and terribly hot baritone story. Leader Sahib at work. More splendid and husky baritone in No Time For Cries and the polyrhythm party of Mai Ding, which links Africa, Cuba, Dizzy’s big band of the late 1940’s and the blues. Pandemonium.

Vocalized breathy flute plays the leading role of the lithe Harvey’s Tune. Finally, the big band goes modal and finishes off the session with The Crosseyed Cat in good spirits. Nineteen fellows dangling like puppets on the magical string of Sahib Shihab. Lasting a mere 37 minutes, And The Danish Radio Group is as short as they came in the LP market, but nobody is dealt short here. One only wishes contemporary artists in the CD/download era would limit themselves to half hours of coherent programs instead of hour-long expressions of the ego.

This little big band platter’s on fire.

Check out Shihab’s masterpiece on YouTube here.