Manager Maja Lemmen (70) has been taking care of business at the Dutch jazz club and cultural theatre Porgy & Bess ever since Eve bit the apple. She started out in 1960, when she had moved in with the family of Porgy founder, Frank “De Neger” Koulen. “But when I was 17, I wanted out. I was going crazy, you know how it goes, puberty! But Frank said, ‘you? You’ll never get out of this place!’ He was right. I was holding on to dear life, working hard and getting involved with the beautiful music called jazz.”

Early summer sun. Saturday’s shopping crowd is leisurely strolling in De Noordstraat, which, like many streets of our brave new civilisation, puts best foot forward to guard off the gulf of retail stores in favor of small enterprises. Clothing, shoes, household appliances, books, delicatessen… And, right in the middle, Porgy & Bess. The vintage bar, self-made floor, the painting of exotic black girls, pictures of jazz legends and the portrait of Frank Koulen on the wall. A jukebox underneath, tables in front of it. Terracota walls, various brass instruments hanging on the ceiling. The dark nightclub interior at the back of the club, the performance area, where the Steinway grand piano is hidden under a black sail cloth. Right in the middle of that area, Maja, Miss Porgy & Bess.In 2017, the club will celebrate its 60th Anniversary. Quite a feat for a jazz club, to say the least. A cult hero of mythic proportions ever since he passed away in 1985, the Suriname-born Frank Koulen arrived in Dutch Flanders with the Allied Forces in 1944, married Vera van den Bruele and transformed their tearoom into a jazz cafe. With it, Koulen, the only dark-skinned person in town, hence “De Neger”, forever changed the cultural life of the medium-sized harbour city Terneuzen and the Benelux jazz landscape. Koulen, eternally short of cash but always brimming with ideas and socially conscious visions, introduced streetparades, staged Dixieland and modern jazz, as well as various cultural festivities. Lively entertainment for the youngsters of the day. After his passing, a dedicated army of volunteers and passionate sponsors rebuilt Porgy & Bess (also literally) from scratch and made Porgy & Bess what it is today, a world-wide known, highly acclaimed jazz club.

But what if Maja’s mother hadn’t taken a cab to fetch a ball of wool at Van den Bruele’s wool and linnen shop? One can only guess. “That shop was right in front of future tearoom and jazz club Porgy & Bess. We had recently arrived from Rijswijk. My mother had heart problems so she took a cab. Frank was working in the store and, curious as he was by nature, asked about her un-Flemish, big city accent. A friendly talk. Then, in that charming, pleading tone of his, Frank asked, couldn’t her daughter help out on Friday nights? That’s where I get into the picture.”

When did jazz come into the picture? Maja, adding a stirring touch to the story in the way old sailors recount a legendary shipwreck, explains: “Well, the Koulen family, including seven kids, was great, but it was quite a transistion of course. Then Santa Claus gave me a transistor radio. I had this sparsely furnished room, just a bed and a table, a footstool. So I took the little radio under my blanket, couldn’t sleep, it was about three in the morning and suddenly, I heard something…. Afterwards the announcer said it was John Coltrane. Dizzy spells, heart beating! That beat of Coltrane, and the inherent blues, amazing. It was Radio Brussel. The man said, ‘dear listeners, until next week.’ Yes! From that moment on, I was hooked. In an odd turn of events, I seemed to be taken by an invisible hand. And a voice that said, ‘come, come with me, you’re not alone anymore…’”

“When I got older, I started thinking about the background of jazz. About, for instance, Strange Fruit. I’ve heard it being performed countless times here, by Lillian Boutte for instance, but I never really thought about it, until one day it clicked. The hanging, the drama… It was a protest song at heart. An eyeopener for me. I think it also took Frank a while until he realised where he came from. From black men who’d had a hard time in a white world, essentially. That’s why he felt close to the black performers who came over. Initially, Frank was a straight New Orleans Jazz guy. One day Piet Noordijk played in Porgy. He had a row of saxes lined up on stage. Frank said, ‘Hey, you’re not going to experiment, right?!’” Maja laughs. “But when people like Hans Zuiderbaan and Frans de Ruyter programmed modern jazz, Frank also veered towards that style eventually. Improvisation, melody, but still recognisable mainstream jazz. The emotion of it, Frank dug that.”

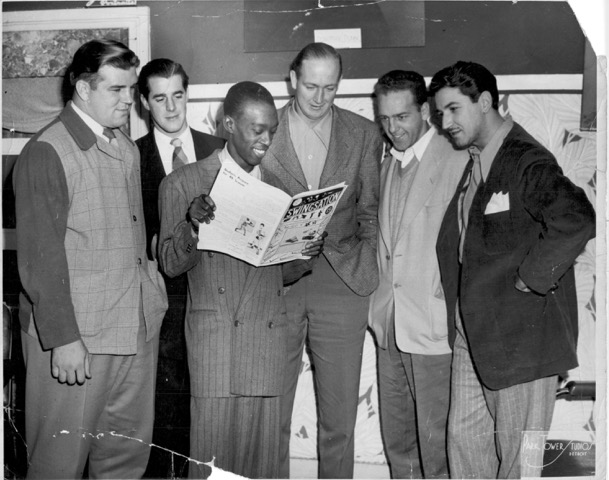

Practically every musician I’ve met celebrates Porgy’s striking hospitality. Many compliments are written down in Porgy’s monumental series of guestbooks. Not a hint of hesitation on Maja’s part when she’s asked about its origins. Clearly, the good-natured, creative, fanatic import Terneuzen fellow, Frank Koulen, instilled a sense of pride and joy that remains in the minds of Porgy’s people to this day. “O yeah, that comes out of Frank. That’s an un-Dutch thing, you know. Frank is notorious for shaking the hands of every incoming customer. Talking about a welcome! As far as food and lodging go, it wasn’t a case of plainly setting up a table of cheese sandwiches. No, Frank cooked exotic meals for the guys, took them out and invented all kinds of ways to make them feel comfortable. It’s a matter of ‘giving’, you know. He raised and trained us in this respect, definitely.”

A good student, Maja, cum laude for sure. But it takes a responsive, giving soul as well, to keep it up for so many years. Lemmen turned into a true jazz ambassador, a temperamental host to both musician and audiences. At heart, it’s a family affair. “You may be right. Porgy, and the group of people attached to it, is like having a family. A sense of pride is involved. I keep meeting people who say that they’ve discovered the jazz life at our place. That’s wonderful! You know, a man named Joop van Tatenhove walked in here years ago. He had a father who was a regular visitor in the sixties and seventies. Joop, a seaman, had moved to Terneuzen, came in and said, ‘I would like to offer my services as a volunteer as a way to offer my gratitude for the fact that Porgy & Bess enriched the life of my father.’ Now, if that ain’t the power of music, right?!”

To say that Roy Hargrove would settle for an apartment near the Westerschelde sea is overstating, but the trumpeter’s kinship with the Porgy family is evident. He performed in Terneuzen as a young lion in the mid-nineties. Since then, Hargrove has made sixteen appearances at Porgy & Bess. “The European tours of Roy, and of other Americans as well, usually start or started in Terneuzen. It is a way for them to start off in a relaxed matter, settle down for a few days. Take bicycle tours along de Schelde. It reminds them of the Hudson, I think. Then they rehearse in the afternoon. That’s cool, here I’m tending business, filling fridges, making phone calls, and meanwhile listening to their music. That’s why I’m so rich!”

And, as an afterthought: “There might be a jam on Saturday before the official gig on Sunday afternoon.”

That’s a fact. Yours truly once attended an unforgettable jam, with Hargrove and Gregory Hutchinson leading a pack of local young heroes till the dawn’s surly light. It’s one of many great Porgy experiences. As a Terneuzen native, I spent many hours in Porgy & Bess and although up north for years now, drop in regularly. I’m grateful that the generous Maja and crew provided me and my friends with a great, warm-blooded place to hang out; with a stage for jam sessions, performances as a singer and the release party of a novel. Moreover, I have fond memories of performances of, to name but a few, Benny Golson, Rein de Graaff with David “Fathead” Newman and Houston Person, and Chicago blues outfit The Red Devils.

Indeed, the list of performers at Porgy & Bess is impressive and ranges from legends like Arnett Cobb, Freddie Hubbard and Archie Shepp to modern luminaries as Danilo Perez, Christian McBride, Joe Lovano and European top musicians as Toots Thielemans, Philip Catherine and Jesse van Ruller. And, of course, Art Blakey in 1982 and Chet Baker in 1985. “To hear Chet play and sing was like being in heaven. Otherwise, Chet was on his own, soft-spoken and, you know, classy in a sleazy way. There was this regular customer, a strong-willed fellow, who came back from the toilet. He said (raspy voice), ‘Hey Maja, you gotta take a look in the john, there’s this junkie fellow, I wonder did this guy buy a ticket?’ It was Chet, of course. Slender, greasy hair, his woodchopper’s shirt…”

Art Blakey was another lasting experience. Maja: “Before his show, Art Blakey was sitting behind the drum kit for a long time. The group, (including the young Terenche Blanchard and Donald Harrison, ed.), was upstairs. There were two little girls milling about the stage, giggling, humming, having fun. Blakey had a broad smile on his face, sat enjoying that scene the whole time. Then, when the band came on, Blakey set off a long sermon about the merits of jazz, it was exciting. You know that deep voice… And he and the band swung like mad, of course. That groove was out of sight!”

Warm-hearted memories. Decades ago. We’re writing 2016 on the wall of the world now. Terra could use some uplifting jazz vibes. Will Maja ever retire? “Ah, they don’t put musicians in nursery homes from the moment they’ve turned 65, right? As long as I’m not too feeble, I’ll go on. Excluding local events, programming is not on my plate anymore, I’m tending daily business, dividing tasks between Pascal and me. I’m, as I often say, the ‘multi-functional household tissue’. The prospect of continuous household activities means I’m keeping close to where it’s at!”

Maja Lemmen

Maja Lemmen (Lexmond, 1945) is the manager of jazz club and cultural venue Porgy & Bess. Porgy & Bess celebrates its 60th anniversary in 2017. It has been host to Nat Adderley, Rob Agerbeek, Monty Alexander, Chet Baker, Art Blakey, Paul Bley, Ray Brown, Ray Bryant, Don Byas, Betty Carter, Philip Catherine, Jimmy Cobb, Al Cohn, George Coleman, Johnny Copeland, Ronnie Cuber, Lou Donaldson, Dr. John, John Engels, Fapy Lafertin, Hein van de Geyn, Astrid Gilberto, Wolfgang Haffner, Slide Hampton, John Handy, Benjamin Herman, Jimmy Knepper, Lee Konitz, Diana Krall, Lazy Lester, Harold Mabern, Charles McPherson, James Moody, The Paladins, Horace Parlan, Cecil Payne, Nicholas Payton, The Red Devils, Rod Piazza, Dave Pike, Art Porter, Rita Reys, Arturo Sandoval, James Spaulding, Lew Tabackin, Rene Thomas, Cedar Walton, Kenny Werner, Mark Whitfield, Nils Wogram, Phil Woods and many others. Porgy & Bess also stages classical music matinees, roots music, and much acclaimed literary evenings.