On audience with Jarmo Hoogendijk, trumpeter that reminisces on the impact of befriending Woody Shaw and sophisticated teacher that found a balance between old-school mentoring and modern education. “Better leave that study room once in a while and have a ball.”

Sparkling sounds, vibrant cadenzas, sassy sideways to the outskirts of chords, crystal clearly phrased and balanced lines of stories that reflected the ethos of the great helmsmen like his mentor and house guest Woody Shaw and updated it for the fin de siècle of the 21st jazz century. Dutch trumpeter Jarmo Hoogendijk was a frontrunner of the generation that gave jazz new élan in the late 1980’s and beyond, featured in the acclaimed Ben van den Dungen/Jarmo Hoogendijk Quintet and the Afro-Cuban big band Nueva Manteca. He began his career in the prime Dutch big band The Skymasters and further played alongside Freddie Hubbard, Teddy Edwards, Clark Terry, J.J. Johnson, Frank Foster, Junior Cook, Art Taylor, Rein de Graaff, Cindy Blackman, Rufus Reid and Lewis Nash. Irreparable problems with his embouchure untimely ended his career as a professional jazz musician in 2004.From that moment on, Hoogendijk extended his teaching career with the same flair that he displayed as a professional musician. Today, Hoogendijk is mentor and teaches trumpet, ensemble and vocals classes at the conservatories of Rotterdam, Amsterdam and The Hague. Hoogendijk himself graduated at the prehistoric boulders of jazz teaching. The system had been under construction since the 1970’s and teachers were jazz heroes that invented methods on the spot, among others pianist Rob Madna, trombonist Erik van Lier, saxophonist Ferdinand Povel, trumpeter Ack van Rooyen and pianist Frans Elsen. “It was like the Wild West. Reportedly, Ben (van den Dungen, FM) once had a musical dispute with Frans Elsen and things got out of hand in a bar. Suddenly Ben was on top of Frans, fists clenched and shouting: ‘Don’t expect me to be afraid of you, rotten dwarf!’ The thing was, next day they let bygones be bygones. That’s how it worked back then. Beautiful era.”

Nowadays, the conservatory landscape is strongly professionalized, an area of draught-free buildings with double-glazing and solar panels, so to speak. No need of renovation. Or is there? Critics do not pull any punches. Hoogendijk acknowledges sore points but proudly defends his line of work. Intelligently rebutting presumptions seems second nature to the blond-grey resident of mainstream jazz city #1, The Hague, who receives the Flophouse crew at his neatly arranged apartment just outside the city center. A record cabinet looms large over his shoulders in the anteroom. Newspapers and Doctor Jazz Magazine are on the kitchen and coffee table.

FM: When was the first time you saw Woody Shaw perform?

JH: “In March 1985. I went to see Freddie Hubbard but his performance was cancelled and was replaced by the Woody Shaw/Joe Farrell band. Before the gig, Woody was in the foyer alone. I saw him doing Tai Chi exercises, that was quite a sight. The concert blew my head off. He was so incredibly in top form, unbelievable! He played 20+ blues choruses and the intensity and originality grew with each chorus. That gig was recorded on cassette. I immediately started to research his solo’s.”

FM: When was the first time you met him?

JH: “That was in 1986. I went to George’s Jazz Café in Arnhem with Ben. Woody played with the Cedar Walton Trio. We got to talking. From then on we met at concerts. Woody regularly stayed at the place of road manager Bob Holland. I met him over there and we chatted and studied together. Sometimes I took him out on a trip or to concerts or he visited my shows with Nueva Manteca. At some point, he was at my place and asked if he could stay overnight. Eventually, he stayed a couple of weeks and that was the last time that I saw him. It was pretty intense because Woody was quite a volatile character. People that act on such a high creative level are sensitive and vulnerable and sometimes self-destructive. And probably as a consequence things can get rough. Woody was like that. Wise but someone who in reality doesn’t know how to cope with life! But despite all of this, we also laughed a lot.”

FM: What do you do when you have Woody Shaw as a sleepover?

JH: “Listening to music, chatting. Doing groceries, cooking. And going to jam sessions. Back then I lived right beside café De Sport, a flourishing and legendary jazz spot. At that time in his life, Woody rarely touched his instrument. But one day he said, ‘Ok, I feel like playing a bit’. We went to De Sport where the regular trio of pianist Frans Elsen featuring bassist Jacques Schols and drummer Eric Ineke was playing. Physically, Woody was in bad shape. But his playing was totally enchanting. I remember that he played The Man I Love, very subdued and humbling. When we finished, Woody made clear that he wanted to go home and have some sleep. This was very unlike Woody! He said, ‘I believe that this was the last time that I played.’ Incredibly and unfortunately, it was.”

FM: He was one of the great innovators of jazz trumpet and a keeper of the flame, preaching modern jazz at a time when fusion was the big thing.

JH: “Definitely. If there is one trumpeter that embodies the whole history of jazz but who is totally original, it’s Woody. What more could you ask for? His playing echoed Louis Armstrong and at the same time was super hip. It’s the max. When Shaw lived in Europe during the last years of his life, few musicians actually knew who he was or how great he was. If you ask about Shaw nowadays, many trumpeters pick him as their big favorite.”

FM: What are your favorite Woody Shaw recordings?

JH: “My favorites are live recordings. I think, however great he was, that he was less comfortable in the studio. Live is a totally different ballgame. Those posthumous albums that were instigated by his son Woody III, like the Bremen and Tokyo albums, as well as the the High Note releases, are unbelievably good. How can someone who lives such a chaotic personal life act at such a continuous high level? It’s astonishing. I have a lot of bootleg cassette tapes from live performances and radio broadcasts from the 1970’s and 1980’s. That’s when you hear him playing totally different and original versions of the same compositions night after night. Truly amazing. His memory was fabulous and his ears were pitch-perfect.”

FM: What did you learn from Woody Shaw?

JM: “Study at least 8 hours a day when you’re young, over and over again. That’s the only way to become great at what you do. But also have a bit of a ball, go out, experience life. Woody was absurd. His constitution must’ve been very strong. Same goes for Freddie Hubbard and Wynton Marsalis, I think. Woody studied eight or nine hours every day, then went to a gig and a jam session afterwards. Every day, every week, on and on. Who can put that thing in his mouth for so long? Woody III told me that he should not dare to come in his dad’s room with this or that message, like ‘telephone’ or ‘dinner’s ready’. He just didn’t hear him and kept on playing! He was one with the trumpet. But he also partied hard.”

“Woody heard me study a couple of times. He rarely gave comments but one time he said: “Man, don’t try to play like me. You’re not ready for that stuff. First listen to Lee Morgan and his cadenza on Night In Tunesia. Then we’ll talk again.””

FM: I have the feeling that students today are too well-mannered. Well at least for my taste. Where’s the son of a bricklayer that kicks ass? I realize this might be false romanticism.

JH: “Think twice. I’ve seen plenty of very talented youngsters go berserk. That’s what happens with the ones who already have a lot to say on their instrument. If somebody threatens to go overboard, we will have a talk. But I will be honest and mention that I was no saint! But as a matter of fact, I’m more worried about students that are always dressed immaculate, whose hair is neatly combed and who are never a minute late and perfectly prepared. No mistaking, that’s good. But then again, something must be wrong!”

FM: How do you teach? A bit like your mentor, the late great Ack van Rooyen?

JH: “The things he said took a long time to sink in. Ack talked about developing stories, grabbing the listener’s attention, becoming a unity with the rhythm section. And putting that thing out of your mouth now and then. These realizations come with age. I’m sure that some of my students will sometimes mutter, ‘what’s that old sock saying?!’ Ack was beautiful, we went to jam sessions together till the wee wee hours but be in class next morning at ten. He was very kindhearted but also to the point. I remember one time, I was playing a piece and Ack said: ‘Yes, Jar, you have no trouble handling the trumpet, but I haven’t heard anything beautiful.’ Bam, uppercut. But then he touched my arm and said: ‘The power of youth…’. Beautiful. As a teacher you need to be supportive but able to say things like, ‘ok, fine but your timing is bad.’ I also strictly believe in the advice of Stan Getz, who said that ‘the only thing you need is better players around you.’”

FM: Aren’t there too many students? Each year, graduates try to find work in a relatively small cultural environment.

JH: “Well, every faculty group needs a diverse section of instruments to sustain ensembles. I realize that not everybody becomes a star performer. There are students that are not entirely convincing but nevertheless demonstrate plenty of progress after the first year. There’s that side of the coin. From all my trumpet students in my career, there is only one that dropped out. The rest is involved in music one way or the other, whether as a recording artist and performer, teacher, event organizer, in an orchestra section or semi-professional. I do have one proposal. It would be good if we had the possibility to end associations with students in the 2nd or 3rd year. Not to be harsh, but to give them a chance for a couple more years with a more suitable education. However, the legal basis is tricky.”

FM: Conservatories teach skills. Shouldn’t they focus more on finding personal styles?

JH: “You’re nowhere without grammar, vocabulary, skills. And finding styles in the beginning equates with copying. Even the greatest innovators in jazz initially were imitators of their heroes. As a teacher, you have to be flexible. The choice is theirs. Some students graduate without a very distinctive style. Still, they usually end up somewhere in the creative industry. As others are concerned, it’s all about elaborating on the phrasing, timing and dynamic that our voices have developed since birth and not about the notes but how you play them. What they play is a matter of preference. A lot of students experiment with odd meter. That’s fine. But it’s not new by any means. Is that really the core of your story?”

FM: I read pianist Kaja Draksler saying that ‘the lack of originality today is not only due to the conservative teaching techniques but also to the tendency to urge the students to describe that unique sellable aspect of their music. Schools dedicate hefty chunks of self-advertising, press kits, promotion etc. It’s better to focus on music.’ Do you agree?

JH: “That’s a good argument. I’d like to add some comments because there’s more to it. You need to have some background. Nowadays, there is a worrisome focus on diversity and inclusion. In essence, these concepts are ok. But now they are part of governmental strategy. It’s coercion and part of the general tendency to undermine ‘elitist’ art. But you can’t put artists and art forms on the same scales. The result is that clubs and theaters are forced to adapt to top-down norms. The norm is what sells and then you get more of the same.”

“The mindset of students and musicians subsequently drifts towards diverse and inclusive projects. That’s why Eastern instruments, predominant in the experiments of the 1970’s, are used again. It’s exotic. It’s forced by the institutions. Without the ud or sitar, it’s hard to get a grant! That’s my complaint. Exactly because I feel that every new thing is ok with me but it should be introduced without outside force. One of the all-time lows was a rapper that fronted the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra. That’s what they call ‘coloring outside the lines’. It was very painful. It’s like herring topped with whip cream. Imagine how all those violinists felt. All those years of studying and now this. I’m a fan of classical music and I respect the genre of rap. But in all fairness, the best backing group for the rapper is his posse.”

“What the establishment should do is focus on kids and start with free tickets, as the leftist politician Jan Marijnissen once wisely proposed. Or else it should be no problem to invite school classes to rehearsals at concert halls, sit between musicians or listen to explanations of the conductor. Same goes for jazz. There are plenty of jazz personalities with great stories.”

Jarmo Hoogendijk

Selected discography:

Ben van den Dungen/Jarmo Hoogendijk Quintet, Heart Of The Matter (Timeless 1987)

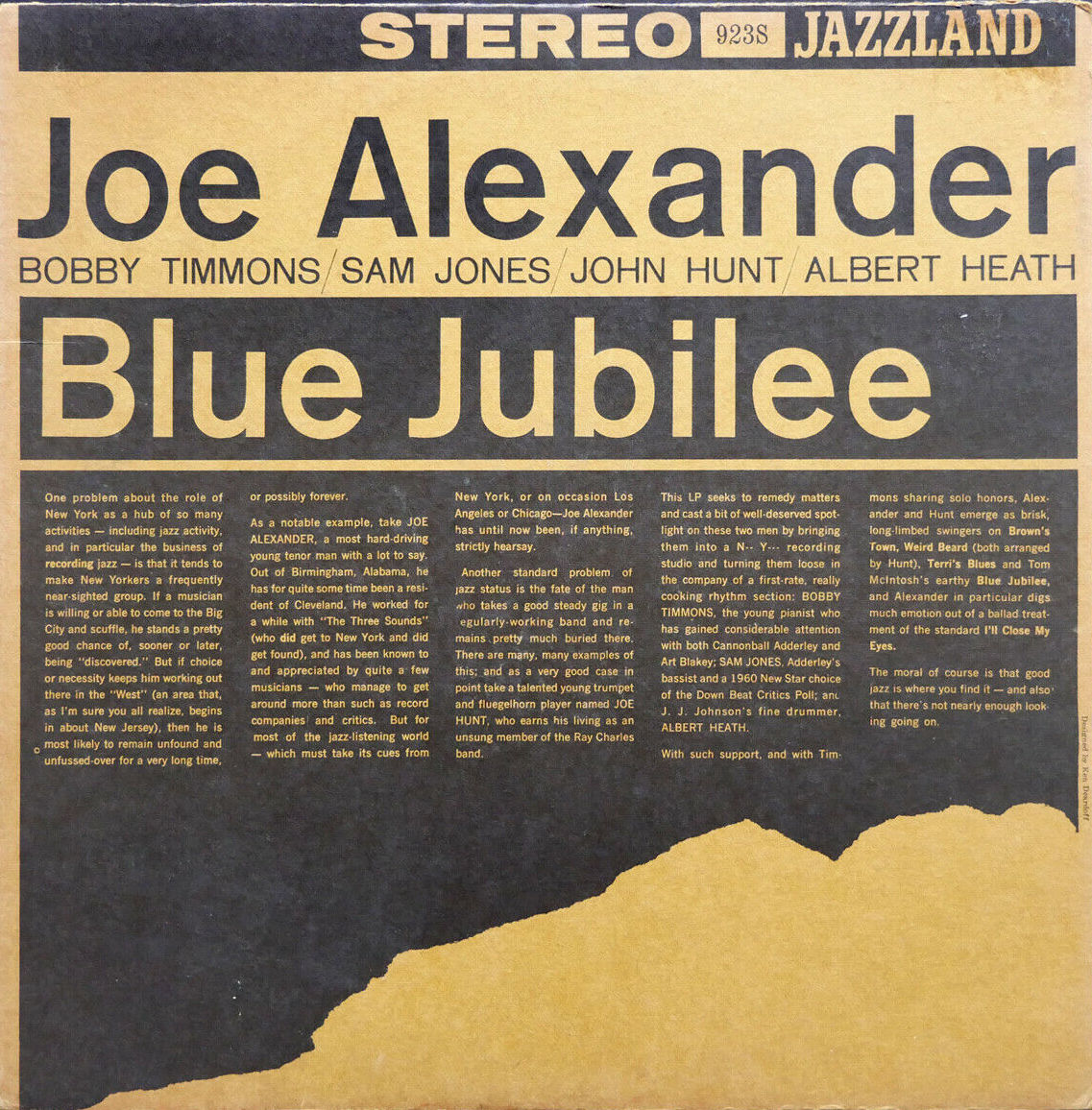

Rein de Graaff/Dick Vennik Quartet & Sextet, Jubilee (Timeless 1989)

Rob van Bavel, Daydreams (RVB 1989)

Nueva Manteca, Afrodisia (Timeless 1991)

Bik Bent Braam, Howdy (Timeless 1993)

Ben van den Dungen/Jarmo Hoogendijk Quintet, Double Dutch (Groove 1995)

Nueva Manteca, Let’s Face The Music And Dance (Blue Note 1996)

Beets Brothers, Powerhouse (Maxanter 2000)

Check out Jarmo’s website here.

Here’s Jarmo Hoogendijk as part of the interview series of the Dutch Jazz Archive Jazzhelden.