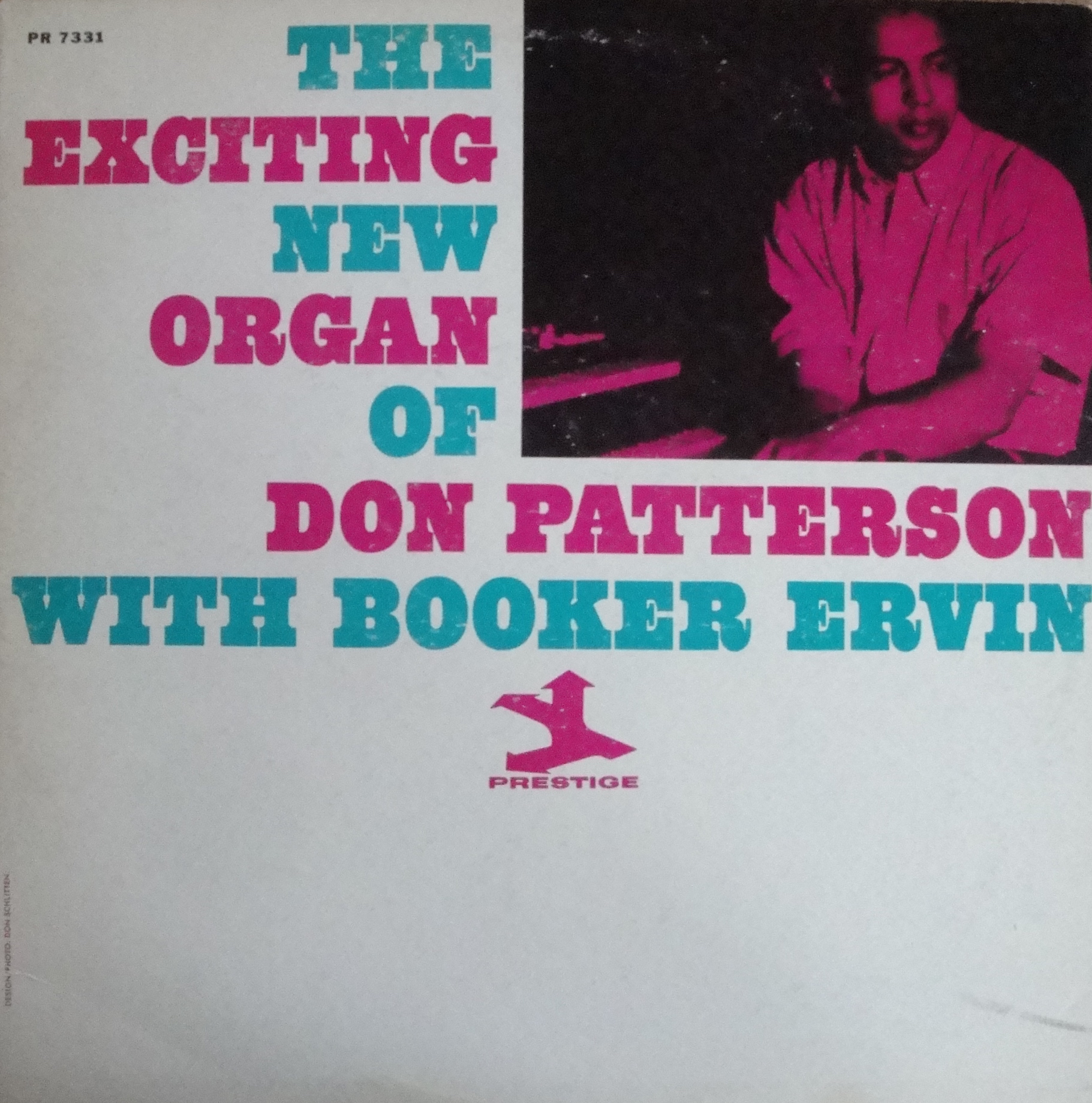

A very confident Don Patterson made the most of his de facto debut (Goin’ Down Home was a Patterson session as a leader for Cadet in 1963, but was not released until 1966) on Prestige. Eschewing the use of guitar, The Exciting New Organ Of Don Patterson stresses the potential of the organ in the era of advanced hard bop.

Personnel

Don Patterson (organ), Booker Ervin (tenor sax), Billy James (drums)

Recorded

on May 12, 1964 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as PR 7323 in 1964

Track listing

Side A:

S’Bout Time

Up In Betty’s Room

Oleo

Side B:

When Johnny Comes Marching Home

The Good Life

Presumably, as it goes, Prestige headquarters called it The Exciting New Organ Of Don Patterson for marketing purposes primarily, along the same lines of, for instance, Atlantic’s idea behind Ornette Coleman’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come; not a title Coleman was said to be particularly fond of, and I assume Patterson also was too bright and modest to appreciate his album title very much. Furthermore, isn’t it a bit shaky on a linguistic level? Naturally, it isn’t the organ of Don Patterson that is exciting. As if said Hammond B3 would make an entree in some corner bistro, where two Scarlett Johansson-type dames’d whisper: “Wow, that organ’s really exciting!” Albeit a tad overweight, one might add. Of course, what they say, either consciously or winsomely, is that the man seated behind that giant machine made up of wood, metal tonewheel, electromagnetic pick-up, a row of keyboards and countless pulls and stops, creates quite a fervor. In that case, they’re correct. As far as ‘new’ (music) is concerned: the adjective had become stale even by then; in jazz, as in most art forms, an artistic endeavor is never completely new, but adds fresh (entertaining and/or often disconcerting) views to an already rich heritage. It’s partly new though in the manner hereafter discussed.

Three years of experience playing alongside tenor and alto giant Sonny Stitt saw Patterson cooperating with guitar player Paul Weeden, and the remaining decade he would strike up an engaging companionship with Pat Martino. Martino and Patterson certainly inspired eachother to career heights. Without the guitar, however, Patterson is far from handicapped. The dynamics are not so much better as different. A whole bit of elbow room is created and judged by the manner in which Patterson takes it, for him it must be assumed a welcome deviation from the organ/sax/guitar-format.

Whereas in When Johnny Comes Marching Home Patterson doesn’t stray far from the methods of Jimmy Smith (who recorded the traditional tune on Crazy Baby in 1960) – in renaissance terminology Patterson surpasses imitatio and comes close to aemulatio – Patterson original S’Bout Time is a whole different ballgame. By far the album’s greatest achievement, (eclipsing the rendition of Sonny Rollins’ Oleo, itself a fine performance that receives meticulous attention to its tricky theme and a fair dose of fast-fingered bop-blues riffs from Patterson and tenorist Booker Ervin, and Up In Betty’s Room, a lively blues composition containing some freewheeling improvisation as well as a too distorted B3 sound near the end) S’Bout Time stretches the boundaries of soul jazz by way of a modal “feel” reminiscent of the work of contemporaries such as Joe Henderson, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock. Horn and piano players, yes, since theirs is the broad-minded approach Patterson felt comfortable with and challenged by.

A sassy build-up from drummer Billy James and Patterson’s “walkin” bass lines is followed by a simple melody that is somewhat in the vein of (a speeded-up) So What, from whence Booker Ervin takes off. And I do mean take off! Ervin, an astute contributor to many of Charles Mingus’ finest recordings, is fiery all the way, splendid in his combination of blues and the depth of Coltrane. Patterson’s answer to Ervin’s spontaneous combustion is dynamic, coherent, unashamedly freeflowing. With only two chord changes to play with, and no percussive guitar obstacles, Patterson really stretches out, leaving smart spaces, playfully running up and down the scale and veering from robust behind-the-beat-accents to delicate, suave bopeology. Patterson uses his right hand almost exclusively and the effect is mesmerizing. After four and a half minutes of classy soloing, Ervin re-enters for a few heated bars and the trio trades fours down to the coda.

It’s a powerful statement from a refreshing record of organ jazz.