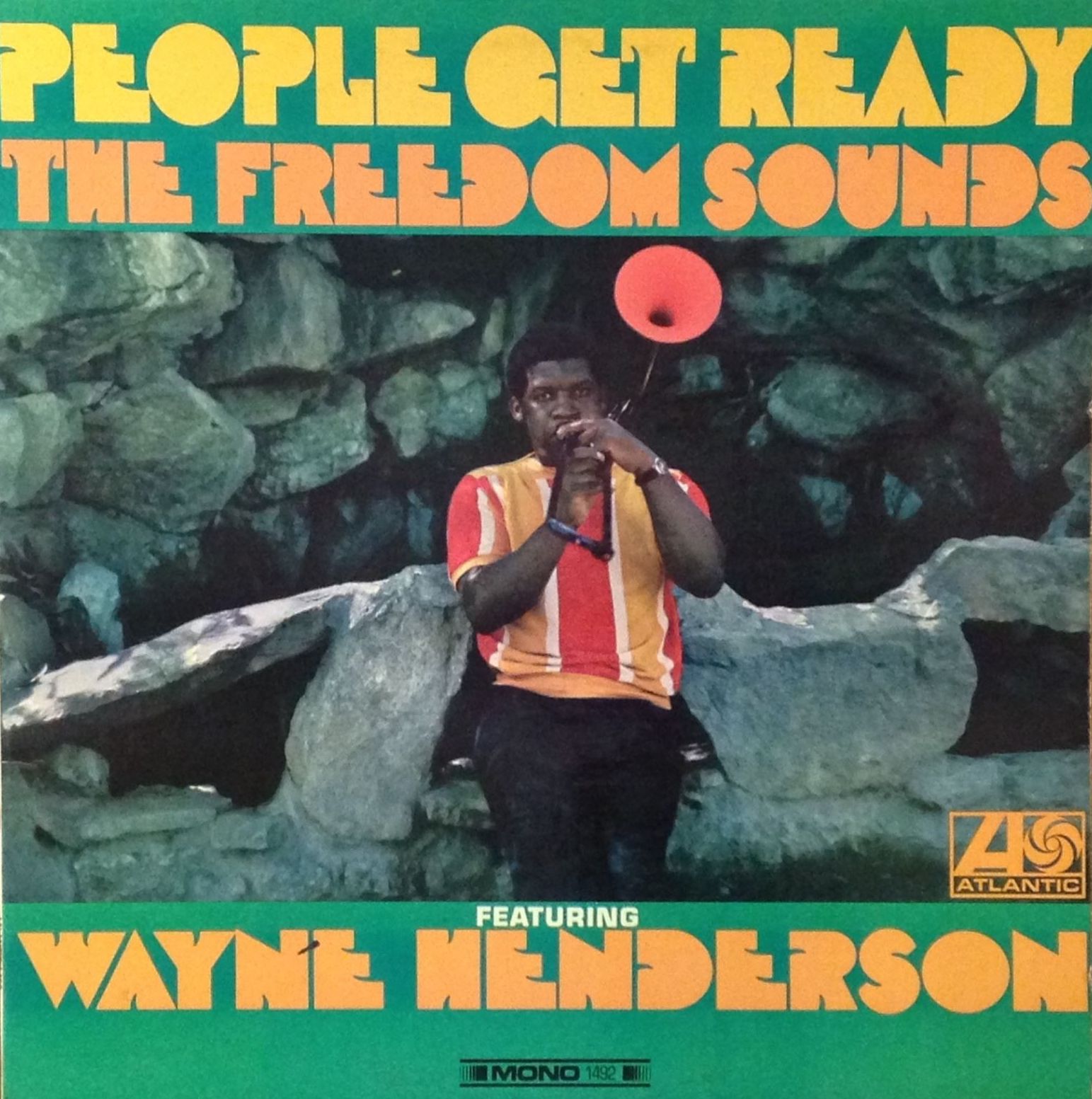

Soul power and gargantuan trombonism on People Get Ready, the 1967 Atlantic album from The Freedom Sounds Featuring Wayne Henderson.

Personnel

Wayne Henderson (trombone), Al Abreu (tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone), Jimmy Benson (baritone saxophone, flute), Harold Land Jr. (piano), Pancho Bristol (bass), Paul Humphrey (drums), Max Gardano (Bells, bongos), Moises Oblagacion (congas), Ricky Chemelis (timbales)

Recorded

on July 7 & 10, 1967 at Gold Star Studio, Los Angeles

Released

as SD 1492 in 1967

Track listing

Side A:

Respect

People Get Ready

Cucamonga

Things Go Better

Side B:

Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa (Sad Song)

Brother John Henry

Orbital Velocity

Cathy The Cooker

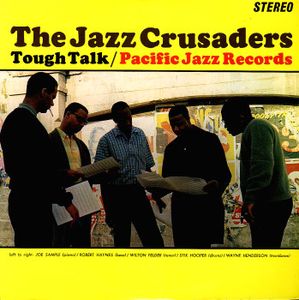

Like his friends from the Jazz Crusaders, pianist Joe Sample and tenor saxophonist Wilton Felder, Wayne Henderson was an active participant in other projects, even more so during the years when the group transformed into a more funk and pop-oriented outfit under the guise of The Crusaders. As early as 1967, Henderson founded The Freedom Sounds, which released two LP’s, People Get Ready (1967) and Soul Sound System (1968), vibrating, jazz-coated hodgepodges of soul and Latin music.

Sandbags in front of the door won’t stay the tsunami of sound emerging from The Freedom Sounds. Certainly an outcome of Henderson’s robust trombone style leading the way to the shore and the multi-layered percussion blend of drums, congas, bongos and timbales beneath it like a thick carpet of pebbles and seaweed. But definitely it must also be attributed to the engineering excellence of Atlantic Records, which by 1967 had gathered a wealth of recording experience with jazz, soul, pop and r&b, producing giants like Otis Redding, Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin and Joe Tex and therefore was perfectly attuned to the kind of superjazz Henderson envisioned would add to his and the label’s already imposing reputation. Preceding People Get Ready, a few of the sessions with big ensembles that Atlantic recorded were Freddie Hubbard’s High Blues Pressure, King Curtis’ Plays The Great Memphis Hits, Aretha Franklin’s Aretha Arrives, Herbie Mann’s The Beat Goes On and Eddie Harris’ The Electrifying Eddie Harris.

Usually the major-league engineer Tom Dowd turned the knobs at Atlantic Studio in NYC, unless the recordings in the soul field were at Rick Hall’s famed Fame Studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. But by the absence of Dowd an array of engineers took care of business. Here we have Doc Siegel and Stan Ross, this time at Gold Star Studio in Los Angeles. Anybody who is familiar with these guys, raise a finger. Assumingly, the duo was based in California. For sure, they are freelancing providers of soundalicious excellence. The sound quality is a kick in the butt, punchy resonance enhanced by the virtue of mono density that retains the force of stereo spaciousness.

Like the engineers, the group members are largely unknown. Al Abreu? Splendid tenor and soprano saxophonist with a penchant to joyfully move to the outer fringes of the mainstream atmosphere. Pancho Bristol? Seldom heard a better-sounding name for a Latin jazz bassist. Moises Oblagacion? Seldom heard a better-sounding name for an Afro-Latin conga player who, authorities of Latin music will point out, played on the obscure gem Introducing The Afro-Blues Quintet Plus One in 1965. Harold Land Jr. on piano? Like, I hear customers of a dimly-lit, teeny-weeny jazz bar in Osaka whisper in each other’s ears to the music of the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet, the son of the great saxophonist Harold Land? Sure ‘nuff. People Get Ready is Land Jr.’s debut and throughout a fulfilling career, Land Jr. played with, among others, Gerald Wilson, Roy Ayers and, no surprises there, his father. Drummer Paul Humhprey, on the other hand, does ring a bell. I’m surprised to find he’s the featured drummer on a number of albums at the Flophouse headquarters, notably by Les McCann, Charles Kynard and Gerald Wilson. West Coast cat, obviously. Humphries has also been working successfully in r&b, funk and pop music.

The renditions of Otis Redding’s Respect and Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa (Sad Song) are juicy oranges, concise, crafty gems. Henderson wrote a number of fresh, energetic tunes: Cathy The Cooker has a lithe Latin groove, while Orbital Velocity, in the same vein, spells danger hi-voltage, sends the listener to a dance on the ceiling, somewhere in the vicinity of Havana, Cuba. The hefty soul groove of Brother John Henry is marked by a stupendous transition from the end of the melody to the following chord sequence. It’s like watching Lionel Messi step up a gear, avoid a tackle, sneak between three players and place the ball into the net over the dumbfounded keeper with a gracious movement of his instep. The crowd goes berserk.

Seriously, Sly Stone would’ve freaked out if he’d heard Cucamonga. Perhaps the burgeoning genius of psychedelic popsoulfunk really did. Henderson, like Sly, is able to put a lot of stuff in a tune without sacrificing its energy and coherence. Cucamonga has uptempo groove, slow groove, rousing breaks, probing reed riffs, furious soprano sax and the rotund r&b figures and outerspacy voicings of Harold Land Jr. A piece of lurid, roaring soul jazz ill-suited for the morose neckties gathered at the yearly convention of insurance companies in San Diego. Maybe if they do listen, their lives just might have changed irrevocably, like the crowd that watches Messi.

The wall of sound and rhythm and the tacky infusions of modern jazz phrasing of the title track, Curtis Mayfield’s/The Impressions’ People Get Ready, leaves one gasping for breath, only to send one movin’ and groovin’ on the floor, like just about the total repertory on the waxed offering from the 28-year old trombonist and his freedom sound fighters. Two albums, People Get Ready and Soul Sound System comprise a most concise discography. But of course a short, exciting career is to be preferred over generic swan songs. Arguably, Wayne Henderson and his gang of 8 had wrung out every drop from their soulful mindset, like tough old maidens wrenching bathing suits, the job done, the catharsis complete. We’re a winner.