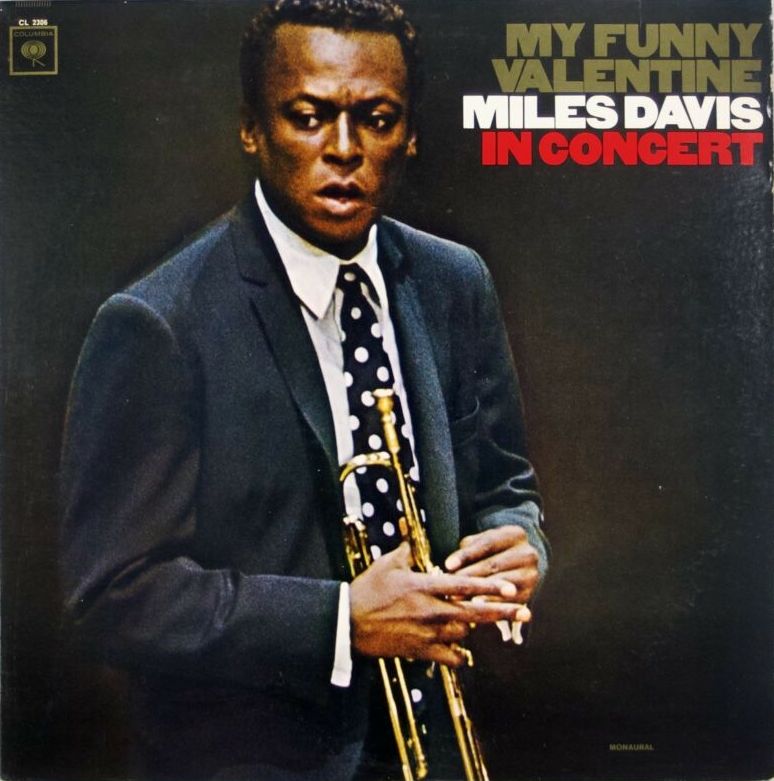

As the development of the Civil Rights Act reaches its climax in 1964, Miles Davis records My Funny Valentine, sophisticated masterpiece of his Second Great Quintet.

Personnel

Miles Davis (trumpet), George Coleman (tenor saxophone), Herbie Hancock (piano), Ron Carter (bass), Tony Williams (drums)

Recorded

on February 12, 1964 at Philharmonic Hall of Lincoln Center, New York City

Released

as CL-2306 in 1965

Track listing

Side A:

My Funny Valentine

All Of You

Side B:

Stella By Starlight

All Blues

I Thought About You

Elation and awe fight for first row. You know what I mean what happens when listening to My Funny Valentine, Miles Davis speakin’ his piece in 1964 with his Second Great Quintet, which features tenor saxophonist George Coleman (the ‘iconic’ 2nd would include Wayne Shorter), pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams. In the year of 1964, on the day of February 12, two days after the long-awaited Civil Rights Act was set in motion, Miles Davis, significantly, records for release My Funny Valentine, not his first and not his last beautiful example of black jazz, a statement at once refined and sleazy, haunting and down-to-earth, entertaining and thoughtful. It is commonly overlooked that the performance at The Philharmonic Hall of Lincoln Center in New York City was co-sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Congress of Racial Equality.

At the milestone date of February 10, the Civil Rights Act was passed by the House of Representatives. Delayed by a filibuster (the democratic right to oppose against a proposal by means of endless strings of speeches in the Senate – Frank Capra’s great movie Mr. Smith Goes To Washington starring James Stewart gives an enlightening and riveting view of the filibuster process), the Act was finally approved by the Senate on June 19 and on July 2 was signed into law by President Johnson, who had taken office after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in the fall of 1963.

The Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin and constituted a defense mechanism against voter discrimination, racial segregation in schools and public places, and employment discrimination. It was an extension of CRA 1957, which powered by the case of Brown vs Board of Education rendered segregation in schools unconstitutional and protected voting rights.

Legends goes that John F. Kennedy was a driving force of change. President Kennedy was admired by the Afro-American community. Musicians paid homage. Alto saxophonist Andy White named his band The JFK Quintet. Booker Ervin lamented his passing on A Day To Mourn on his Freedom Book record. Even Miles Davis, usually not so generous with applause, remarked in 1962: “I like the Kennedy brothers. They are swinging people.”

Why put cigarette paper between those two sentences by the Dark Prince? If anything, the young and energetic Kennedy’s indeed had plenty of style. However, the truth is that it was only after severe pressure – the Birmingham Campaign, protests, lobbies, the March on Washington – that JFK became supportive of new legislation. Moreover, there actually is very little evidence that Kennedy showed any sign of action on his part concerning the betterment of the standard of living for Afro-Americans in the years preceding his presidential career. He may not have been a bad cat but fact is he slept through the major part of the afternoon. The Afro-American love for JFK is sincere but speaks volumes about the standard of alternative political leadership.

To think that, during the tense zeitgeist of the mid-sixties, no one took care to pay Davis’s young crew of George Coleman, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams for their services on the special night of February 10. Nada, zip, zero!

Two LP’s were culled from the Miles Davis Quintet’s performance: Four & More and My Funny Valentine. Four & More is fast and furious, My Funny Valentine is slow to medium-slow and supple. Both are killer achievements, though the former album, consisting of up-tempo tunes (taken up a notch) offers no relief and that is one of the reasons I prefer My Funny Valentine.

No album titled My Funny Valentine could consist of breakneck speeds. The only tune with a reasonably fast tempo is the Davis staple All Blues. It is a typically organic group effort and includes a solo climax by Miles Davis that makes the children jump off their stools in the circus tent. Does not somehow this music of the Second Great Quintet prefigure that great flexible band of Woody Shaw featuring Carter Jefferson, Larry Willis and Stafford James in the mid-1970’s? Just a thought.

The ballad readings of the flexible Davis quintet are exquisite. Listening to the quintet is like following a sailboat in an Olympic event that anticipates the differing weather conditions, which range from calm to breeze to gusty wind. Captain and crew are quite the match on the gulfs of Stella By Starlight, All Of You and I Thought About You, all of which are developed, interestingly, without unisono ensembles and Captain Davis stating the melody. Tension between vulnerability and chutzpah is a Davis forte and developed to the max during All Of You, which is marked by ever-so-slight trumpet whispers and Davis’s patented pastel colors. The captain invites an eager response from the crew and climaxes with an upward, fearless cadenza.

The thoughtful but solid lines of George Coleman contrast nicely with the brooding fantasies of Miles Davis. It was said that Tony Williams felt that Coleman’s style was too polished and conservative and that was the reason Coleman hit the dust. Coleman always maintained that it was him that flew the coop and that it was only after reading the Miles Davis autobiography that he learned about Williams’s opinion. In his autobiography, Davis by the way stated that Coleman was damn well able to play rough and free if he felt like it and once sustained a wild avant ride during the total course of a concert just to thumb his nose to the young lions in the band. Coleman eventually integrated some avant techniques but only if they were to the advantage of his purely melodic and balanced style. That is why I love George Coleman. Eventually, his style has proved rather influential.

Coleman’s ending of his solo of the title track, the pièce de résistance of this great quintet, sounds like a violin, a touching tag to a lovely, balanced story. No small feat, considering that he followed one of the finest Davis solos on wax. Davis’s kaleidoscopic colors and bends stay close to the melody but at the same time are played in such a way that you see My Funny Valentine in a new light. You hear at work not someone who plays changes but an architect of sound and emotion.

Instead of smashing his notes through the wall of the fortress, Miles Davis seduces the gatekeeper such that he opens the gates totally bedazzled and entranced.

Funny Valentine’s looks are laughable, unphotographable. Yet, she’s his favorite work of art. Brave high notes end the impressionist painting of Miles Davis, full horn climax that ignites subtle and smooth and propulsive swing. Special evenings require special bands and this eager incarnation of the Second Great Quintet beautifully performed its duties.